Who is an expat?

It’s a simple question, but it’s far from easy coming up with a succinct and satisfactory answer. With globalised travel and work habits increasingly in the headlines, swissinfo.ch enters the semantic jungle of expats, immigrants, refugees and economic migrants.

“I know it when I see it,” was the famous comment by a US Supreme Court judge struggling to define obscenity. Many people have the same attitude towards expats: “I know one when I see one.”

In its most literal sense, an expat – short for expatriate (not necessarily an ex-patriot!) – is someone who lives abroad. That’s how most dictionaries define it. For the HSBC Expat Explorer surveyExternal link, an expatriate is “someone over 18 years old who is currently living away from their home country”.

But for many people that definition is too broad. It could also apply to students, refugees and asylum seekers, who – I would guess for most people – are not expats. So how can we improve on the “adult abroad” definition?

InterNationsExternal link, the “largest expat network in the world”, defines an expat as “someone who decides to live abroad for an unspecified amount of time, without any restrictions to origin or residence”.

More

Escaping the golden cage

External linkThis, it acknowledges, does not differ very much from an immigrant, “usually defined as someone who has come to a different country in order to live there permanently, whereas expats move abroad for a limited amount of time or have not yet decided upon the length of their stay abroad”.

Do you agree? Let’s consider various statements about expats – some deliberately provocative – as food for thought in a search for an overall definition.

Expats intend to stay in their new country for a limited period. This goes back to the days when expats were skilled professionals, usually from large multinationals, sent abroad on temporary assignments. Their dependants were also included. The problem is that, while these overseas postings still exist, this definition covers many other people.

Who of the following are expats? An American diplomat stationed in Ghana. A Ukrainian plumber working in London. A German businesswoman living in Shanghai. An Ethiopian medical student refining her skills at a hospital in France. A Syrian professor working in Italy as a janitor, longing to return to his war-torn homeland once it becomes safe again.

As this blog postExternal link, which originally asked that question, points out, the above definition would say all of them; most people would not agree. What’s more, by this definition people who retire abroad cannot be expats (unless you stretch “limited” to mean “until death”). The British media would have to come up with another term for the 300,000 or so Brits who live in SpainExternal link, a third of whom are pensioners, all of whom are concerned about how Brexit will affect their rights. What will happen to these Brexpats?

Expats have a certain level of income/education. Or they do certain jobs. Does the colour of your collar (white versus blue) affect your expat status? Can a well-qualified, well-educated person who does a menial job, such as the Syrian professor working in Italy as a janitor, be considered an expat?

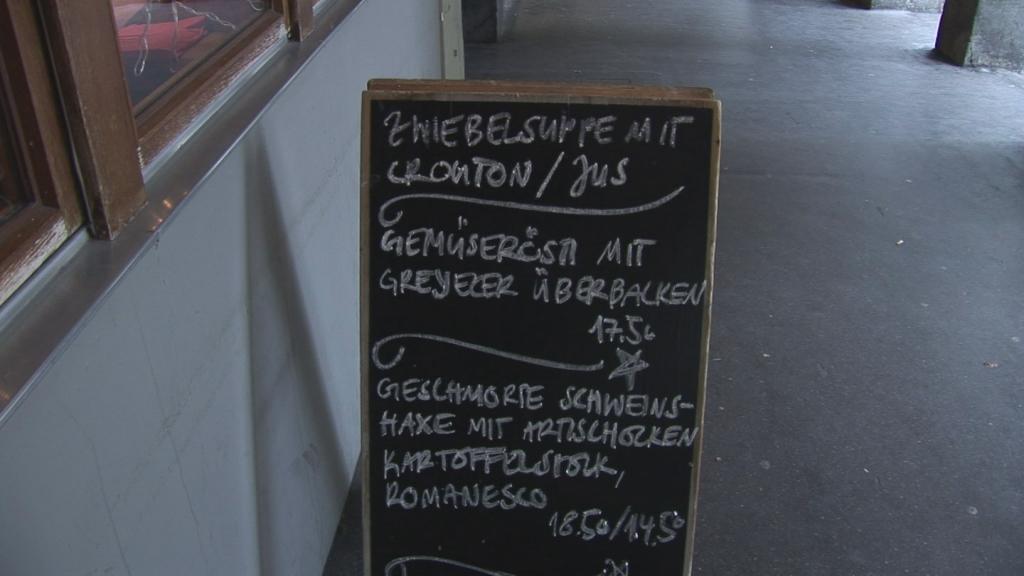

The HSBC Expat Explorer survey for 2015 looked at expats in 39 countries and found that while they earned on average $180,000 (CHF182,300) a year, in Switzerland the figure was $200,000. This doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t be a poor or even unemployed expat, but money appears to play a role.

And let’s ignore émigrés. Tempted as I am to refer to myself by a word which, according to Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage, “carries connotations of intellectual or artistic sophistication”, the linguistic divisions are already confusing enough.

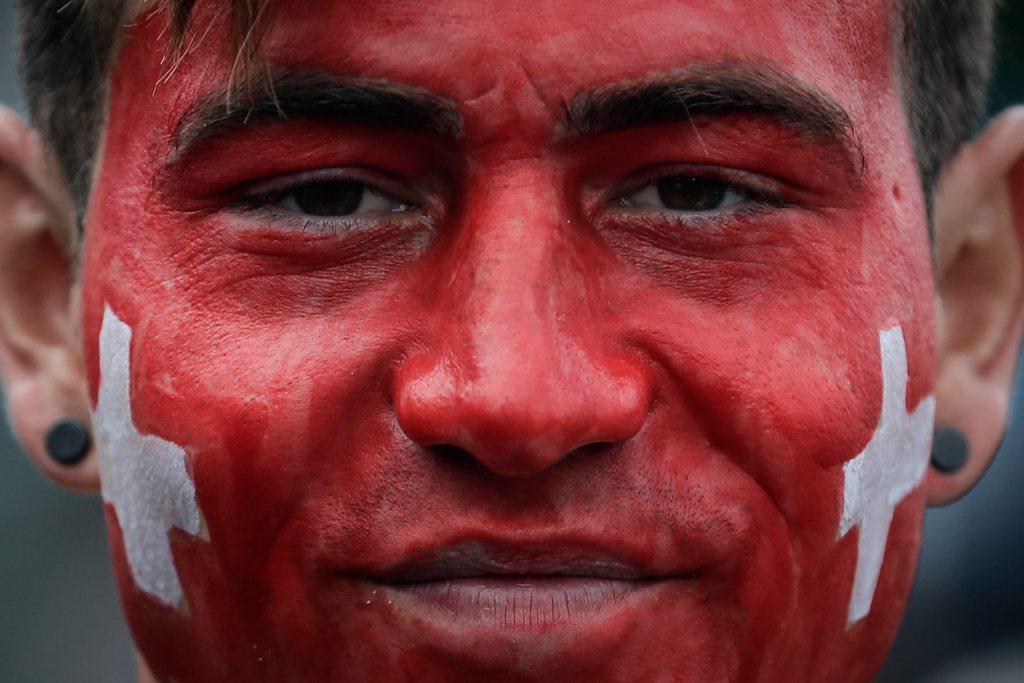

Expats are white. Forget about white collar, how about white skin? Let’s tip-toe through a politically correct minefield.

White people are expats and everyone else is an immigrant, argue some peopleExternal link. This is based on the view that expattery is an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon and a colonial hangover from the days when the English upper-middle classes were disseminated around the Empire (and Switzerland!). Expat hotbeds included Africa, India and Hong Kong, where affluent Brits enjoyed “expat life” in “expat communities”.

The Empire might have disintegrated, but the cultural connotations linked to expats appear to be going strong. As the author of the previous link comments: “Top African professionals going to work in Europe are not considered expats. They are immigrants. Period.”

The annual InterNations Expat Insider surveyExternal link identifies ten common types of expatriates.

The “traditional expats”, i.e. foreign assignees and the expat (travelling) spouses, are only two of them and make up just a fifth of the survey participants.

Others include, for example, one in ten who searched for and found a job abroad on their own, 8% of romantics who move to join their partner in their home country, 7% of former students who came for an education and stayed for a job, 18% of adventurers who simply enjoy living abroad and were looking for a personal challenge.

(Source: InterNations)

Then there is the issue of shades of white. If one judges that Africans or Asians do not qualify for expat status, how about eastern Europeans or olive-skinned Italians or Spaniards, for example? Or for that matter a non-white Brit working in the US? If nothing else, these questions strengthen the argument for dropping the term expat.

But even snow-white continental Europeans don’t make it into the expat club for some sections of the British media, which refer to Brits in Paris as expats but French people in London as immigrantsExternal link.

Expats move down in the world, immigrants move up. According to this interesting theory, which also has imperial overtones, whether you are an expat or an immigrant depends on the relationship between the country you have left and the country you are in. If you “upgrade” countries, you are an immigrant; if you “downgrade”, you are an expat.

While this argument has a superficial appeal, it is quickly refuted by Switzerland, recently named the best country in the world. It would thus be impossible to downgrade to Switzerland, which consequently would be expat-free (it certainly isn’t).

In addition, one of the ten types of expat in the InterNations Expat Insider surveyExternal link is the Greener Pastures Expat, who is “looking for a better quality of life”.

Expats don’t hold a passport of the resident country. The Swiss resident population is 8.3 million. How many Swiss citizens live abroad? If you said 775,000, give yourself an expat on the back. Of these, three-quarters hold dual nationality – are they expats? Most people would say no because a passport is, among other things, usually a sign of integration and…

Expats make no effort to integrate. They don’t learn the language or socialise with the locals. This again goes back to colonial Brits whose only interaction with the local population was hiring them as domestic staff. Expats basically live the lifestyle of their own country while living in someone else’s country, and you need to be rich to do that. Especially in Switzerland.

More

Brits import home comforts

Expats stay by choice rather than necessity. InterNations acknowledges that while the “types of expatriates and the reasons behind their decisions to move abroad are as diverse as the countries they are coming from and moving to, usually though, it is true that for the people we call expats, living abroad is a lifestyle choice rather than born out of economic necessity or dire circumstances in their home countries, such as oppression or persecution”.

That, InterNations concludes, is what differentiates them from refugees or economic migrants, and not their income or their origin.

You might agree or disagree with these statements, but is there actually any point in using – let alone defining – the term “expat”?

On the one hand, it has no legal meaning. There is no such thing as an “illegal expat” and no one would describe themselves as a “second-generation expat”. It also enforces social divisions without bringing any noticeable benefits.

On the other, it is a short, headline-friendly word that the media, especially in Britain, will continue to use, so it is practical to agree on what we are talking about. The concept is slowly entering other languagesExternal link, even if a convincing, unequivocal definition remains a work in progress.

So who is an expat? Well, I know one when I see one.

Are you an expat? Why? What connotations does the word have for you? Should the media stop using the term and refer simply to migrants? Let us know in the comments below.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!