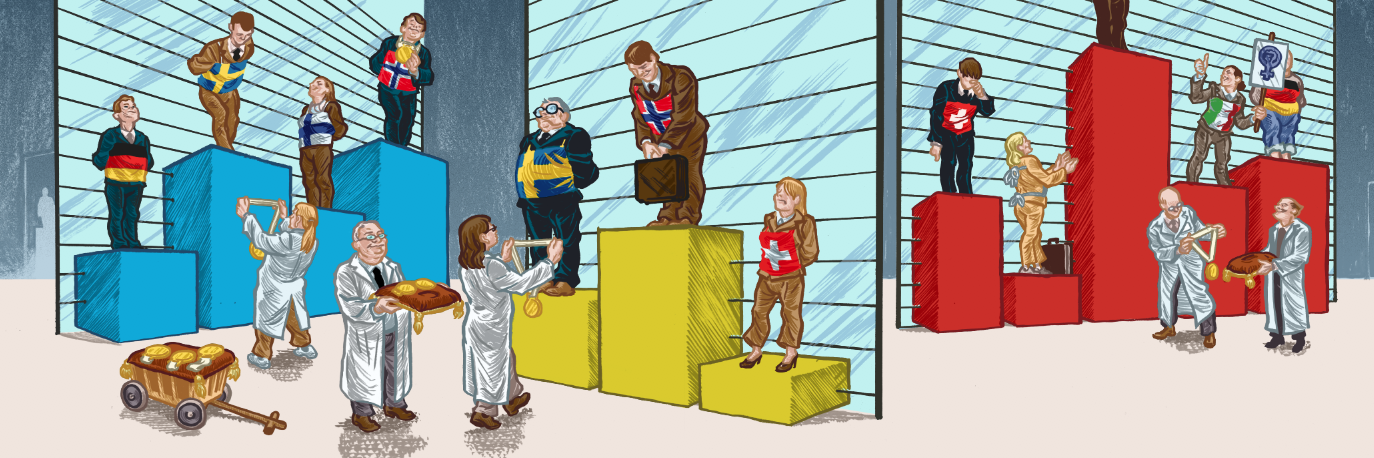

Fifty shades of democracy: can you measure people power?

Comparing countries has become a popular sport across the globe, with annual indexes ranking everything from happiness to health – and democracy. In 2021, democracy is facing its biggest uphill battle since 1989, say the most important measuring institutes.

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted”. Albert Einstein

Switzerland is a “declining democracy”, reports the Washington-based research institute Freedom HouseExternal link in its 2020 report. The reason for this critical assessmentExternal link: “voting rights for a large part of the population are limited and Muslims face legal and de facto discrimination”.

More

Switzerland’s exclusive democracy

The Economist Intelligence Unit,External link (EIU) another well-known democracy ranking group, offers a similar appraisal of the Alpine democracy, but for a different reason: “low voter turnout”. Worldwide, both ranking institutes diagnose an even worse situation in their latest reports: “Democracy was dealt a major blow in 2020External link”, says EIU, while Freedom HouseExternal link summarises: “As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny.” This happens (half) a century after the breakthrough for universal suffrage.

More

How the global battle for female suffrage influenced Switzerland

For a country like Switzerland, which experienced the first successful democratic revolution in Europe in 1848 and which for a long time was a liberal island in a monarchic continent, these critical assessments from international researchers can work as a healthy wake-up call, says Roger de Weck – the author and journalist who published a book earlier this year outlining 12 proposals to make Swiss democracy more democratic.

More

‘The more power citizens have, the more responsible they become’

Switzerland is of course not alone in needing a democratic check-up, especially since the pandemic has thrown up the latest challenge to free societies. But how can a democratic diagnosis be done in a fair and transparent way?

David Altman, professor of political science at the Catholic University of Santiago de Chile and author of “Citizenship and Contemporary Direct Democracy”, has followed efforts to measure democracy for many years: “We are witnessing a return to scientific expertise and evidence-based assessments,” says Altman, who is also one of the architects of the Varieties of DemocracyExternal link (V-Dem) research project – the world’s biggest data collection effort aiming to conceptualise and measure democracy.

PLACEHOLDERV-Dem offers a new approach to the world of democracy measurement: “We employ 170 country coordinators and 3,000 experts, who compile and compare more than 350 different indicators,” says Anna Lührmann, the Deputy Director of V-Dem based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. And unlike similar projects, their statistics are accessible: “Our datasets are open and transparent for all, and can be used like Lego blocks to build your research or analysis,” Lührmann says. Indeed, V-Dem’s open data set is now used by a growing network of international organisations such as the World BankExternal link, Communities of DemocracyExternal link and International IDEAExternal link.

More

The ‘third wave’ of autocratisation and the dangers to democracy

The Gothenburg-based group also publishes its own annual report and uses the data for specific situational reports like the Pandemic Backsliding Risk Index, which reveals that 55 autocratic and 32 democratic countries experienced corona-related limitations to human rights and civic freedoms in 2020.

Unsurprisingly for a sensitive – and some would say subjective – topic like democracy, the rankings are not without critics.

“There are two problems with most democracy rankings”, says Matt Qvortrup, professor of political science and international relations at Coventry University. “First, their raw data are not publicly available; second, their indicators are biased towards traditional forms of representative government”.

As a consequence of such a bias, newer forms of participatory and direct democracy are underrated in the rankings, something which – according to Qvortrup – penalises countries like Switzerland, Uruguay, Taiwan or even Germany and the United States (at the regional and local level). Instead, the ‘participation’ level in some rankings is simply derived from a few criteria like turnout in elections or membership in trade unions. And as a result, Norway – which has no right to referendum in its constitution – is regularly labelled as the most participatory country in the world by the Economist.

In spite of the limitations and challenges linked to the conceptualisation and measuring of people power around the world, the results of such assessments matter.

“Billions of dollars and euros are spent annually on promoting democracy both domestically and abroad”, says V-Dem’s Lührmann. “These investments are contingent upon judgments about a country’s current status and future prospects. For this reason we need proper ways of measuring democracy”.

In the case of Switzerland, this is of paramount importance, as supporting democracy worldwide is a constitutional duty.

More

Switzerland promotes democracy where it hurts

What’s up, doc?

As for the diagnosis: On a global level, according to V-Dem the share of the world’s population living in an autocracy has risen from 48% to 68% between 2010 and 2020. One major reason for this is that India, for a long time the world’s biggest democracy with almost 1.4 billion people, was downgraded to an electoral autocracy in 2021. Moreover, the number of countries where freedom of expression is under threat has grown from 19 in 2017 to 32 in 2020. On the positive side, democracies making progress include two each from Africa (Tunisia and Gambia) and Asia (Taiwan and South Korea).

More

Vote-counting procedures can tame even wild democracies

While the world overall is witnessing a wave of autocratisation, the current third wave of democratic backsliding has new features, however: while earlier waves took place in countries where such tendencies were already in progress, this wave is happening mostly in democracies themselves. And while before, autocratic regimes came to power through foreign invasions or military coups, today the process is subtler and more gradual, and often camouflaged by legal changes.

A typical example of such a “lawful” development towards autocracy is in Russia, where a top-down plebiscite to allow Vladimir Putin stay in power until 2036 was rushed through in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic. Highly questionable practices like this offer a counterpoint to what should be the key ingredients for a functioning democratic society.

More

Ten key ingredients for a democratic society

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative