How distance learning keeps Afghan girls’ education hopes alive

From Bangladesh to Switzerland, grassroots efforts are multiplying to help women and girls in Afghanistan study online in defiance of a ban on education. Rights advocates say it’s time for states to step up pressure on the Taliban to restore this basic human right.

At 19, Mahbube Ibrahimi spends much of her time studying. She’s finishing secondary school in Zurich, her home since arriving in Switzerland just two years ago. If she were still living in her native Afghanistan, Ibrahimi would be shut inside the family home, banned like all girls and women from an education beyond primary school.

Distraught at the situation in her homeland, in 2023 Ibrahimi created an online learning platform for girls in Afghanistan. Called Wild FlowerExternal link, the non-profit venture now has 70 volunteer teachers in Europe and some 120 students in Afghanistan keen to learn subjects like maths, computer science and English. Ibrahimi, whose goal is to reach 500 girls, is gratified by the impact it’s having.

“It’s more than helping,” says Ibrahimi, who as a child fled Afghanistan with her family and grew up in Iran. “For many girls, it’s not just about learning. They have a friend in another part of the world and know that people outside Afghanistan are aware of what’s happening to them.”

Since returning to power in August 2021, the Taliban have curtailed rights for women and girls, shutting them out of post-primary education, work in most sectors and outings without a male guardian. Over two million girls are now out of school in Afghanistan, says Malala Fund, an organisation that champions girls’ right to a free, quality education worldwide.

Wild Flower is just one of countless digital-learning initiatives started by Afghans in exile and non-profits both overseas and in the country to give women and girls a safe space to continue learning. As these grassroots movements try to fill the education gap, the international community is no closer than it was three years ago to getting the Taliban to restore basic rights in the country.

Women’s rights: ‘more of an obstacle than a goal’

Back in 2021 the Taliban takeover prompted world leaders to impose sanctions on members of the group and keep it at arm’s length diplomatically – to date no country has formally recognised the Taliban government. In April 2023, the world’s top security body, the United Nations Security Council, adopted a resolutionExternal link calling on the group to reverse its gender-based restrictions.

But signs now point to a waning momentum to persuade the Taliban to change their ways. This past June, the Taliban agreed to talks in Doha, Qatar, with the UN and around 25 organisations and countries, including Switzerland – but only after women were disinvited. Human rights also remained off the agenda of the meeting, which took place as part of an UN-led effort to explore engagement with the Afghan regime.

Although Rosemary DiCarlo, the UN official chairing the Doha talks, insisted before the pressExternal link that Afghanistan could not “return to the international fold” so long as half of the population were deprived of their rights, the Taliban were unmoved. The head of its delegation, Zabihullah Mujahid, calledExternal link the group’s stance on women’s rights mere “policy differences” with other countries and Afghanistan’s internal matters, which have no place in foreign affairs.

For Sahar Halaimzai, who leads the Afghanistan Initiative at Malala FundExternal link, the Doha talks show that women’s rights are now “seen more as an obstacle than a goal” when engaging with the Taliban. “We’re increasingly concerned about how long it’s taking for there to be any shift in Taliban policies towards girls,” she says.

Three years on, the priorities of the international community have shifted, says Bashir Mobasher, a postdoctoral fellow in sociology at American University in Washington, DC., who’s also started online classes for Afghan women. Countries are focusing more on security, including counterterrorism, given the presence of Islamic State affiliates on Afghan soil. Many, he adds, are also keen on relative peace under the Taliban after 40 years of protracted conflict in the country.

Situation in Afghanistan a case of ‘gender apartheid’

Many rights advocates, however, insist that states should hold the Taliban accountable for abuses. One way to do this, they say, is to recognise the situation in Afghanistan as gender apartheidExternal link, defined as “an institutionalised pattern of systemic domination and oppression on the basis of gender”. Amnesty International sayExternal links that the existing norm of gender-based persecution, though recognised as a crime against humanity, “does not fully capture the scope and reach of systemic domination” that is apartheid.

“Codifying gender apartheid [under international law] would allow us to take girls’ education out of the political footballing we’re seeing around engagement with the Taliban,” says Halaimzai. “It means there would be clear obligations for principled engagement with the Taliban. Girls’ education is non-negotiable. This is a red line that we’re just not seeing at the moment.”

A growing number of states, including Austria, Mexico, Malta and the Philippines, are showing support for adding gender apartheid to the draft treaty on crimes against humanity, according to Halaimzai. “It would be a huge win for this campaign if Switzerland, as a champion of international law and human rights, were to join the many partners and organisations pushing for codification,” she says.

When asked for its position on the issue, the Swiss foreign ministry wrote in an email: “Apartheid suggests two separate systems for different parts of the population, whereas in Afghanistan women and girls are almost completely excluded from public, political and economic life.” Instead, the ministry says, the Taliban could “potentially be accused of crimes against humanity” for gender-based persecution.

More

Our weekly newsletter on foreign affairs

‘Keeping hope at a high level’ for Afghan women

With a reversal of the Taliban’s stance on education seemingly a long way off, the focus of advocates SWI swissinfo.ch spoke to is to help women and girls defy the ban. Malala Fund has so far given $6 million (CHF5.1 million) in grants to organisations both in Afghanistan and abroad that offer alternatives like distance learning.

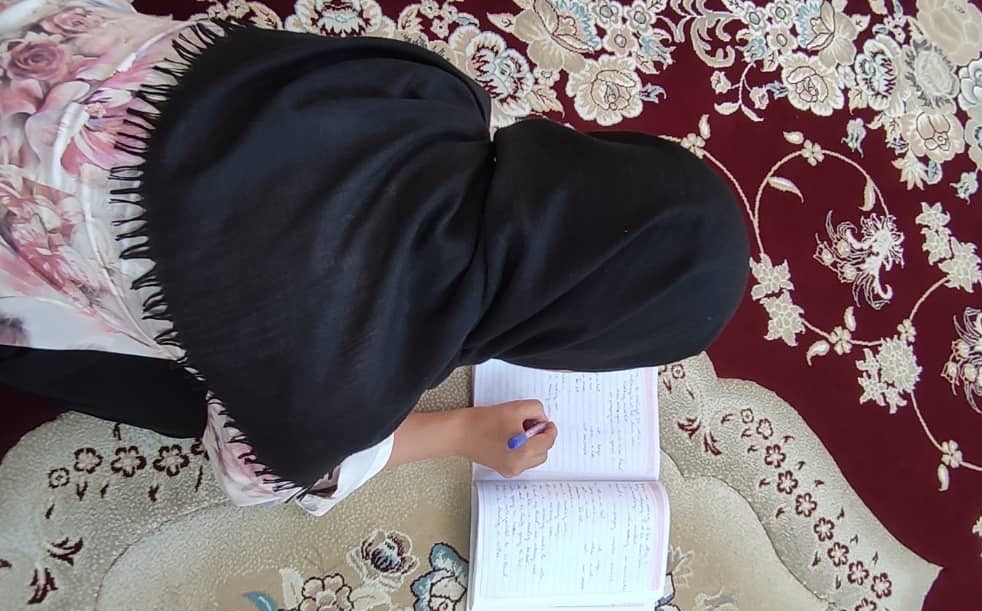

“I finished university just before the Taliban closed schools to women and girls. The Taliban had a rule to not give girls their diploma. They lifted this rule but I’ve been waiting one and a half years for my diploma.

I was so disappointed that as a woman graduating, I can’t go anywhere to continue studying. At first I felt really hopeless, but after a few months, I started thinking, ‘Why am I experiencing these things? I’m here to be strong.’ Since then, I try my best not to lose hope.

I heard about Wild Flower from my friend. I want to study for my master’s degree abroad, so I’m trying to improve my English. It’s good to have a professional teacher so I can make progress. I have class once a week on WhatsApp. Then we have homework to do. I have a sister who’s also learning with Wild Flower.

We don’t have a computer, so I do my homework on paper, then I use an app to transfer scans of my homework to the teacher. In our home, internet connectivity is not good. When I have a class, I have to sit in the yard or sometimes on the roof of the house to get better connection. Of course there is a risk the Taliban will find out [about the online class]. That’s why I delete my messages weekly.

My father and mother are really supportive. They say, ‘Study and apply for scholarships abroad.’ I want to improve all my abilities and then come back to Afghanistan and teach all the girls. I know one day the Taliban will no longer rule. Even though they closed the schools, still we continue learning. They cannot stop us.”

As told by a student of Wild Flower in Herat.

In the US, the digital learning programmeExternal link that Mobasher helped to set up with ALPA in Exile, an association of Afghan scholars that he leads, has around 1,500 registered Afghan students. It offers free university-level courses, such as in languages and law, as well as practical tools.

“We do teacher-training so they can start schools inside their home,” says Mobasher. The group also wants to offer vocational training, such as in hairdressing and tailoring, so women can start clandestine businesses at home and make a living.

In Switzerland, Ibrahimi is adapting to her students’ needs. She’s looking for volunteers with a psychology background to support Wild Flower pupils struggling with their mental health as they remain shut in their homes.

But with just 6% of womenExternal link in Afghanistan reporting having access to internet, online learning is reaching only a small fraction of the female population. It also cannot replace a formal education. Wild Flower lessons, for instance, are given in small WhatsApp groups – with internet access paid for by the organisation – once a week and do not follow the official Afghan curriculum.

More

Student filmmaker in Switzerland highlights plight of Afghan girls

Still, some of its pupils aspire to leave Afghanistan and study abroad, which is why they are keen to learn English (see infobox). But this is difficult, given the expense and the fact that Afghan women cannot leave the country without a male guardian. In addition, few institutions offer full scholarshipsExternal link to Afghan women. One of them, the Asian University for Women (AUW) in Chittagong, Bangladesh, receives 3,000 applications from Afghanistan at each intake, says the head of recruitment, Suman Chatterjee. The AUW, which also runs a distance-learning programmeExternal link for Afghans, now has close to 500 Afghan students on campus.

Chatterjee says the AUW is taking the long view on education. “We are creating women leaders who will take charge when Afghanistan’s regime changes,” he says. “I hope this one comes to an end soon. Our [graduates] will be ready to come back to their country and build a new Afghanistan.”

Until then, online learning is serving as a lifeline for the girls it is able to reach.

“After food, for a human being having hope is really important,” says Ibrahimi. “It’s about keeping this hope at a high level, because it’s helping them to carry on with their lives.”

We spoke to human rights activist Fereshta Abbasi from Human Rights Watch in our podcast Inside Geneve – listen to the episode here:

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sb

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.