Magnitsky case: How Switzerland failed to investigate Russian millions

An in-depth investigation by SWI swissinfo.ch looks at why and how millions in allegedly illicit money from a global Russian tax fraud case were not investigated in Switzerland.

1. Prologue

In 2020 a high-profile investigation published by the independent Russian media outlet Novaya GazetaExternal link revealed that “Swiss nationals flew to Russia to hunt bears and ‘Russian pigs’ and, in return, attempted to obstruct the investigation into the murder of Sergei Magnitsky.” Magnitsky was a Russian lawyer, who died in prison in 2009 under suspicious circumstances while investigating a vast fraud case against the Russian Treasury.

One of the key figures in that investigation was Vinzenz Schnell, who was officially employed by the Swiss federal police but was actually working for the Office of the Attorney-General on cases connected to Russia. Novaya Gazeta‘s investigation uncovered his meetings with Russian officials at upscale Swiss restaurants, along with numerous luxurious trips to Russia.

Schnell said his management insisted these informal settings were necessary to gather information for Switzerland’s “especially important” investigations linked to Russia.

Schnell’s remit included investigating money laundering from Russia to Switzerland. He oversaw the Swiss side of what is now known as the “Magnitsky case”, named after Sergei Magnitsky.

Want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

In 2016, Andreas Gross, a former Social Democrat parliamentarian who had written a report on Magnitsky’s death for the Council of Europe in 2013-2014, was summoned for questioning by the Swiss prosecutor’s office. Gross is one of the rare people contacted for this investigation to have answered our request for an interview.

He was interrogated by Schnell for a full day. The goal of the interrogation, according to Gross, was to discredit him and his report.

Schnell himself said in court in 2019 External linkduring his trial in Switzerland for an unofficial trip to Russia, that the Magnitsky money laundering case in Switzerland should have been closed long ago. To this end, it was necessary to “discredit” Gross’s report and “unmask him”, Schnell told the court.

“My best friend [former Swiss senator and prosecutor who died in 2023] Dick Marty told me that I wasn’t obligated to attend Schnell’s interrogation,” Gross tells SWI. “But I felt that together we could get to the truth, so I agreed.”

In 2021, the Swiss chapter of the Magnitsky case – an international Russian fraud scandal – closed with a ruling by the Swiss Attorney-General’s Office (OAG) stating they had found no evidenceExternal link that would justify charges being brought against anyone in Switzerland.

As part of its investigation, the OAG froze CHF18 million ($20 million) on Swiss bank accounts belonging to three Russian citizens: Vladlen Stepanov, husband of Olga Stepanova, a high-ranking Russian tax official, Dmitry Klyuev and Denis Katsyv.

They had allegedly benefitted financially from this act of fraud and received funds on their Swiss accounts. The OAG confiscated CHF4 million and returned the remaining CHF14 million to the three Russian citizens. The OAG justified its decision by saying that it had only been possible to prove a connection between some of the assets seized in Switzerland and the crime committed in Russia.

In all, the Magnitsky investigation uncovered $230 million stolen from the Russian public purse. Magnitsky was responsible for publicly exposing the fraud case, while representing his client Hermitage Capital Management, then the biggest portfolio investor in Russia. Magnitsky himself was arrested by the same Russian officials whom he had accused of being involved in the fraud case.

He spent almost a year in pre-trial detention and died in November 2009 after being beaten by prison guards. Russian authorities accused Magnitsky posthumously, along with Bill Browder, CEO and founder of Hermitage, as instigators of the fraud case and tax evasion. Few believed that account. In 2010 Magnitsky posthumously received the Integrity Award from Transparency International for his fight against corruption. In January 2014, the Council of Europe approved a resolution named “Refusing impunity for the killers of Sergei Magnitsky”.

This case led to the imposition of international sanctions against Russian officials suspected of involvement in his death and adoption of laws targeting Russian human rights abusers. The Magnitsky Act, named after Magnitsky, was first introduced in the United States in 2012 before being adopted in Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia among other countries. Switzerland never adopted it.

Hermitage Capital, which according to US Department of Justice was a victim of the Russian fraud scandal, initiated investigations in all the countries where the embezzled funds were allegedly laundered.

A criminal investigation into money laundering was opened by the Swiss Attorney-General’s Office in March 2011 in response to Hermitage’s complaint. Hermitage Capital was named as a civil party and participated in the investigation.

It was closed ten years later. The final ruling raised eyebrows among money-laundering experts around the world, specifically because Switzerland confiscated only 25% of the funds frozen and returned 75% to the three Russian citizens.

Switzerland was the only country that decided to return the alleged embezzled funds to Russia. In June 2023, the US Helsinki Commission, which promotes human rights and military security in 57 countries, called for US sanctions to be imposed on Lauber, federal prosecutor Patrick Lamon, who was responsible for the Magnitsky case in Switzerland, and Schnell. The Swiss foreign ministry and the OAG rejected all accusations of the Helsinki Commission. A final decision by the US is pending.

SWI obtained access to the ruling of the prosecutor’s office through a third party. We also analysed Swiss and Cypriot court documents and bank accounts linked to the case. In total we checked over 400 pages of documents drawn from a variety of legal and financial sources, both international and Swiss.

What the documents show is that on top of the initial sum of CHF18 million that was under investigation, another $10 million allegedly embezzled from the Russian Treasury ended up in two Swiss bank accounts belonging to two other high-profile Russian citizens.

Both of these transfers are linked to Dmitry Klyuev, whom US authorities consider to be the mastermind behindExternal link the embezzlement tax scheme. At the time Klyuev was also the owner of seven corporate accounts and one personal account at UBS Switzerland. The corporate accounts were closed in 2010-2011.

These transfers, as well as all of Klyuev’s accounts, were known to Swiss authorities, as official records show, but were never investigated. SWI looks at the origins of these overlooked $10 million, how they ended up in Switzerland, and why they were never investigated by the Swiss prosecutor’s office. The funds belonged to Russian Senator Dmitry Savelyev and Russian investment banker Igor Sagiryan.

All currencies cited in the investigation are those found in the original documents.

The techniques to embezzle funds used in the Magnitsky case were described in depth by journalists at Novaya Gazeta, a Russian media outlet, and at the OCCRP, an international consortium of journalists. Russian police officers confiscated documents and the corporate seals of the Russian subsidiaries of the Hermitage Fund, a British investment company, and then used them to re-register ownership under another name. Subsequently, a series of other dummy shell companies, established by the same individuals, presented fictitious financial claims against the stolen “subsidiaries” of Hermitage Fund. Playing the role of both plaintiff and defendant, they convinced Russian arbitration courts to issue rulings that resulted in massive losses on paper, completely nullifying the original income. Then, armed with documents “proving” that the company had not made any profit, the perpetrators filed an official claim for a reimbursement in the amount of $230 million, which had previously been paid to the Russian Treasury in the form of income tax. The money obtained in this way was then transferred out of the country through a web of offshore accounts.

2. A discredited Swiss investigation

The $230 million embezzled from the Russian Treasury were dispersed around Europe through a complex network of shell companies and bank accounts in suspicious jurisdictions.

Of those, a total of CHF18 million were frozen in Swiss banks Credit Suisse and UBS between 2011 and 2013. Almost half of this money – €8.4 million (CHF8 million) at Credit Suisse – belonged to Vladlen Stepanov, whose then-wife Olga Stepanova was a senior tax official in Moscow. She was responsible for authorising most of the fraudulent tax returns in 2007.

The rest of the confiscated money belonged to two other Russian nationals, including $8.2 million to Denis Katsyv at UBS and Edmond de Rothschild Bank in Switzerland, and $37,000 to Klyuev at UBS.

Lost in layering

Money laundering is a multi-step process, comprised of three stages. The first is called placement, when fraudulent funds are injected into the financial system, including banks, the stock market and insurance companies. Then comes layering, when funds are moved between numerous accounts of shell companies to disguise their origin. The final stage is integration, when criminal funds reach their destination such as a bank account, or are used for purchases, such as real estate.

All of the funds embezzled from the Russian Treasury were layered at least four or five times before reaching their final destinations, whether in Switzerland or beyond.

Layering makes investigating money laundering difficult as the outcome also depends on the collaboration between law enforcement bodies in different countries. Potentially embezzled money can also commingle with legitimate funds, making it challenging for regulators to analyse the origin of the funds.

In Switzerland, in order to establish that money laundering has taken place, the OAG must firstly prove that a predicate offence (felony or qualified tax offence) has been committed; secondly, that assets originating from this offence could be forfeited; thirdly, that the offender intentionally committed an act with the aim of frustrating the forfeiture of such assets; and finally, that the offender knew or should have known that the assets originated from fraudulent funds.

In its final ruling, the OAG justified closing the Magnitsky case by the fact that it had “not revealed any evidence that would justify charges being brought against anyone in Switzerland but “nevertheless […] established a link between some of the assets under the seizure in Switzerland and the predicate offence committed in Russia”.

On the basis of the “method of proportional calculation”, the OAG claimed that CHF4 million that were previously frozen would be confiscated while the rest could not be traced back to the Russian budget.

This means that the OAG estimated the amount of funds that were diluted at each level of layering to calculate how much should be permanently confiscated.

This calculation method is misleading, according to some experts.

“If what the prosecutors are saying here is correct, then we [Switzerland] would be the paradise for money laundering. Maybe we are the paradise for money laundering”, says Mark Pieth, a former member of the G7’s Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering and former head of section for economic and organised crime at the Swiss Federal Office of Justice.

He adds that, “if there are indicators that this money stems from an illegal source, then it has to be blocked”.

In the same decision, the OAG stripped Hermitage Capital of the status of “injured party”, depriving it of the right to oppose the ruling. This means that it cannot oppose the OAG decision to return the majority of the frozen funds to the three Russian citizens.

In effect, the OAG concluded that the sole victim of the fraud that happened in Russia was the Russian Treasury. This aligned with the narrative of the Russian authorities and is contrary to the conclusions of the US Department of Justice.

Hermitage Capital appealed the ruling to the Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona, but it was rejected.

In December 2022 Hermitage appealed to the Federal Supreme Court.

The Federal Supreme Court has yet to deliver a final ruling.

A controversial ruling

The Swiss ruling was widely criticised when its conclusions were made public, both for its decision to send forfeited funds back to Russia and for stripping Hermitage of its victim status. This was contrary to conclusions reached by authorities in the US, Canada, and the United Kingdom, which imposed sanctions on the Stepanovs and Klyuev.

“Illegal money has to be forfeited, whether the victim is the Russian state or Hermitage,” Pieth says.

“In both cases, the federal attorney’s office would have had the duty to block it and keep it. The former attorney-general of Switzerland had a relatively good relationship with the Russian attorney-general. They didn’t really deal with the case adequately,” Pieth adds.

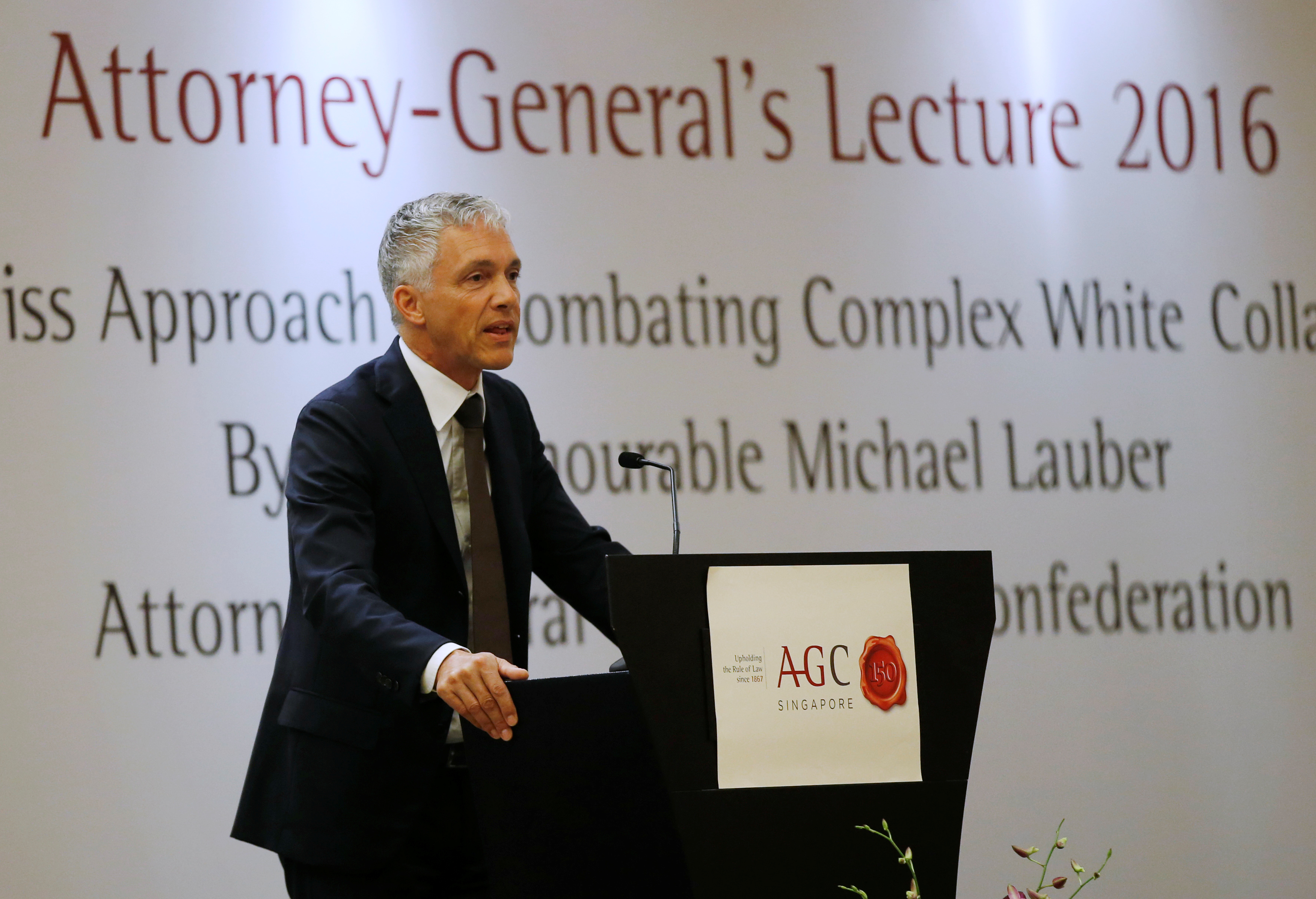

Former Swiss attorney-general Lauber’s close links with Russian officials have been reported on extensively in Swiss and international media. They included lavish dinners, hunting trips and flights on private jets paid for by Russian authorities, as well as downplaying cases of money laundering by Russian officials.

Lauber, under whose supervision the Magnitsky case was investigated for nine years, left his post in 2020 after the first impeachment process ever initiated by the Swiss parliament against a prosecutor. His appointee, Lamon, also known to have ties with Russian authorities, continued the investigation until March 2021. He was substituted by his deputy Diane Kohler. She closed the case four months after she arrived in office.

Schnell’s trial in 2019 showed that he, himself had taken “advantage” of his links to Russian officials in the form of hunting trips financed by oligarchs.

3. New money in old accounts

SWI had access to the full ruling of the OAG, publicly available legal documents, as well as some bank correspondence linked to the Swiss investigation.

Our investigation shows that there were an additional $10 million in Swiss bank accounts that the OAG failed to investigate despite what experts consider clear red flags. The funds – wired to two Swiss banks, BSI LTD (Banca Svizzera Italiana, which merged with EFG International in 2017) and Bordier and Cie – were linked to Klyuev and never investigated by the federal prosecutor’s office.

Klyuev had several Swiss bank accounts at UBS, including two corporate accounts and one personal account. Between 2008 and 2011, the funds linked to the Magnitsky investigations transited from these accounts to other accounts in Switzerland that were not investigated by the OAG – and this despite Klyuev’s former indictments in Russia.

The Klyuev link

The alleged tax fraud was not Klyuev’s first attempt at embezzling funds. In 2006, he was convicted of attempting to steal the shares of another Russian giant, Mikhailovsky GOK, the country’s biggest iron ore plant.External link The Russian press also linked his name to a series of mysterious deaths and assassination attempts.

According to an investigation by the US Department of Justice, Klyuev was involved in another embezzlement scheme from the Russian Treasury totaling some $107 million in 2006. This alleged theft was not recognised as a crime by the Russian government and not investigated.

Klyuev was then-owner of a small Moscow-based bank, the Universal Savings Bank, which was a focal point for his fraudulent activities.

In 2015, Klyuev claimed to Swiss prosecutors that he sold his bank for $1 million in 2006 to a close acquaintance, Russian businessman Semen Korobeinikov, due to its “hopelessly tarnished reputation”. Korobeinikov could neither confirm nor deny Klyuev’s statement. He died in 2008 after falling from the window of a penthouse apartment in a building under construction that he was considering buying in Moscow. A criminal investigation into his death was opened in Russia, then later dropped.

Nonetheless, in 2008, while opening new accounts at UBS bank in Zurich, Klyuev continued to claim that he was the sole owner of the Universal Savings Bank, which was the main bank involved in the $230 million fraud. He did not mention Korobeinikov, nor his sale of the bank, according to documents filed with the bank.

This shows that he was still using his Moscow-based bank for his alleged financial crimes.

The OAG filing and bank documents linked to the investigation all show that an alleged $14.5 million connected to the Russian fraud case transited through Klyuev’s bank accounts at UBS Switzerland.

A total of $4.9 million from his UBS personal and corporate accounts were wired to one of the accounts held by Altem Invest Limited, BVI, at FBME bank in Cyprus.

Part of that money was then wired to another company called Zibar Management Inc. with an account at the same bank. In total, these two companies received some $30.4 million of the $230 million stolen from the Russian Treasury, according to the Hermitage Capital complaint filed in Monaco.

Official documents filed by FMBE bank with Cypriot authorities and seen by SWI show that these two corporate accounts were linked to Klyuev.

Some of these funds stayed in Switzerland to cover his personal expenses.

Klyuev paid CHF218,000 from his UBS account to the Swiss bank Banque Cantonale Vaudoise for the education of his son at a private international boarding school in Switzerland between 2007 and 2010. After Klyuev’s account was closed in 2011, school invoices continued to be paid from FBME Cyprus accounts of Altem in 2010-2011 and then from FBME Cyprus accounts of Zibar in 2012.

Bank records also show that in 2008-2009, Klyuev used his Swiss UBS account to pay the medical bills of his ex-wife, Olga Tamarkina, at a private hospital in Geneva.

The OAG filing clearly identifies Swiss prosecutors were aware of these flows. The filing shows that the funds can be traced from Russia through Moldova, Ukraine and Latvia before they were credited to Klyuev’s accounts at UBS in Zurich. Swiss authorities initially froze $37,000 on Klyuev’s accounts. Following their investigation, Swiss prosecutors found no grounds for confiscating that money.

Laughing all the way to the bank

In September 2019, at least $2 million from the Klyuev UBS accounts were wired to another Swiss-based business account. This belonged to Athina Corporation, which is registered as a company in Panama and has a Swiss account at Bordier and Cie, a private bank in Geneva. The beneficial owner is a Russian businessman called Igor Sagiryan, according to the Swiss investigation.

Sagiryan is not a new name in the Magnitsky case. His business connections with Klyuev go back to the period preceding the fraud. Kluyev was initially hired as a consultant for his bank, Renaissance Capital Group, in 2002. That same bank was identified by the US Department of Justice as being directly linked to the Russian tax fraud case.

In 2023, an investigationExternal link led by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), an international consortium of journalists, and Important Stories, a Russian website specialising in investigative journalism, revealed that both businessmen had invested some of the embezzled money into the elite Cypriot resort Cap St Georges. Sagiryan also has links with other individuals linked to the fraud, including the Stepanovs. An internal investigation by Hermitage Capital showed External linkthem travelling together to Dubai in 2008.

Sagiryan, when contacted by SWI, did not reply to our request for comment.

Friends will be friends…

The OAG filing points to another transfer of funds linked to Switzerland. A total of $8 million appeared between 2012 and 2013 on the corporate bank accounts of Russian senator Dmitry Savelyev and his wife Olga.

The two companies, Green Island Investors Corp, BVI and Roy Finance SA, both had accounts at Swiss bank BSI LTD, which has since become EFG International, a bank based in Lugano. The funds were wired directly from Zibar Management Inc, one of the companies linked to Klyuev with bank accounts at FBME in Cyprus.

Since the transfer, Savelyev has been sanctioned by the United StatesExternal link UK,External link the European UnionExternal link, and Switzerland for voting in favour of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

This is the first time that Savelyev’s name is linked to the Magnitsky case. He is the highest-ranking official allegedly involved in the tax fraud. His name is well known in Russia: he was a member of the Duma, Russia’s lower chamber of parliament, from 1999 to 2016, and has been a member of the Senate, Russia’s higher chamber, since 2016.

SWI established one potential link between Klyuev and Savelyev. Both served in Afghanistan, where it’s highly probable they met. In 1986, Savelyev was drafted by the Soviet Army, where he served in the Limited contingent of troops in Afghanistan. Klyuev was there at the same time as a commander of a military reconnaissance unit. Both have military awards.

Journalists from the investigative media outlet “Important Stories,”External link External linkwho had access to the same sources as SWI, sent an interview request to Savelyev and his wife. At the time of publication, Savelyev had not responded.

Swiss banking law requires banks to alert authorities if they suspect any transfers linked to illicit funds. Despite Klyuev’s conviction in 2006 – a fact that was public knowledge – he continued to have a banking relationship with UBS in Switzerland, both under his name and as a beneficial owner of various companies.

“Ultimately, the bank takes responsibility for working with this or that client,” says Ilya Shumanov, the head of Transparency International Russia, based outside of Russia.

“We know of several examples in Switzerland where bank employees turn a blind eye for politicians or officials, despite issues appearing in the analysis of the origin of the funds”.

In Switzerland, there is no standard procedure that clients must follow to prove the origin of their funds. Banks differ in the documents they request. These can be as simple as a self-declaration by the client. Other banks can require detailed paperwork tracing back the origins of the funds by several decades.

“Before, banks would do a quick internet check on their clients”, says Carlo Lombardini, a law professor at the University of Lausanne. “Today they are much more diligent. I would say that what was possible before would no longer be possible today.”

UBS, EFG and Bordier and Cie were contacted by SWI. All banks refused to comment.

“No Russian oligarch comes directly from the street to a Swiss bank,” says Shumanov.

“There is always a connection through local lawyers, offshore registrars, accountants, and companies that handle all financial operations and tax consultations in Switzerland. This chain ensures formal compliance with standards for the Swiss bank while creating the appearance of the legality of the origin of the funds.”

4. Outstanding questions

In its 179-page ruling, the OAG clearly indicates why it decided not to investigate these two transfers to accounts belonging to Savelyev and Sagiryan as well as Klyuev’s accounts in Switzerland.

Lawyers and experts with whom SWI shared the ruling confirmed that it raises questions about Switzerland’s will to investigate alleged embezzlement. They point to potential dysfunctions within the investigation led by the OAG.

“Contrary to popular opinion, the public prosecutors’ offices in Switzerland are highly politicised, and the OAG is particularly so. The public believes that our criminal prosecution authorities act independently and impartially, but this is not true,” says Giorgio Campá, a Geneva-based lawyer specialising in business law and economic crime.

Regarding Klyuev’s accounts, the ruling argues that the OAG cannot “determine whether they included funds from the Russian treasury” because “the complexity of the diagrams…makes it impossible to follow the flows”.

However, the ruling shows that Klyuev’s accounts at UBS received money from the same shell companies that had sent funds to the Swiss accounts of the Stepanovs – which were investigated and partly seized by the Swiss prosecutor’s office.

The two shell companies, Nomirex Trading Limited and Bristoll Export LTD, had accounts at Trasta Komercbanka Latvia (the European Central Bank revoked the bank’s licenses in 2018 for not complying with money-laundering regulations). They simultaneously wired funds to companies linked to Klyuev and Stepanov.

It is not clear why the OAG considers transfers to Stepanov to be illegal and connected to the fraud, while transfers from the same source to accounts belonging to Klyuev were deemed “impossible to follow”.

“If money first goes to Switzerland, then to Cyprus, and then in repackaged form ends up back in Switzerland on corporate accounts at BSI Bank, then this is money laundering – the usual way of laundering money,” Pieth says of the OAG’s decision not to investigate Klyuev’s accounts. “But what is Switzerland’s role in all of this?”

As a professor of criminal law and criminology at the University of Basel, Pieth followed the case closely right from the start. He provided a formal testimony to the Helsinki Commission on Switzerland’s handling of the investigation.

“I simply don’t know how on earth a serious attorney-general could have turned a blind eye,” Pieth says. “This is outrageous. Saying it’s too complicated would mean Switzerland would be a paradise for money laundering. I have real difficulties in understanding whether this authority really is doing its job.”

‘Unjustifiable decision’

The OAG also argues in its ruling that “the companies [of Dmitry Klyuev] were making payments prior to the offence”. This suggests that a company which existed before an alleged crime occured should not be investigated.

The OAG justifies not investigating Savelyev’s accounts at BSI LTD by saying they were opened “almost three-and-a-half years” after the embezzlement of the funds and that both Dimitry Savelyev and his wife were not under investigation at that time.

“Consequently, there is no reason to follow up the requisition which is rejected”, the ruling said of those accounts.

This is inconsistent with the OAG’s own logic and conclusions.

The OAG confirmed that the company owned by Stepanov, called FARADINE Systems, was opened in March 2010, so two and a half years after the fraud. Despite this, it was from that account that Switzerland decided to confiscate CHF4 million.

The $2 million transfer from one of Klyuev’s UBS corporate accounts to that of Athina Corporation belonging to Sagiryan, and which appears in the ruling, was also never investigated.

The only mention of Sagiryan’s name in the ruling is a question to Vladlen Stepanov on whether the two knew each other. According to the filing, Stepanov replied that he did not know Sagiryan.

When contacted, the Swiss prosecutor’s office said that they were unable to comment on a case while criminal proceedings were pending.

“The discontinuation order has been contested by several parties involved, which is why jurisdiction and thus powers have been transferred to the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Supreme Court. As a result, the authority to communicate in this context has also been transferred to the court,” the prosecutor’s office said in an emailed response to SWI.

SWI contacted several lawyers, parliamentarians and law professors to comment on the ruling and the incoherences it underlined.

At the time of publication, only a few had agreed to comment, both on and off the record. In informal conversations with SWI, some lawyers said they would rather not criticise a ruling of the prosecutor’s office.

“This decision appears legally unjustifiable,” says Campá, the Geneva-based lawyer. “It would appear to fall within the scope of a ‘discretionary’ filing, which is prohibited by Article 7 of the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure, which enshrines the need to prosecute. The facts under investigation, especially when they are complex, require further investigation into elements directly related to them. Prosecutors cannot decide to ‘look the other way’ when they must be driven solely by the search for the material truth.”

Michael Lauber’s Russian ties

Former Swiss Attorney-General Michael Lauber, who oversaw most of the investigation, was known for his strong ties to Russia. His time in office (2011-2020) was tainted by allegations of cover-ups of Russian corruption cases. These include an investigation into former Agriculture Minister, Yelena Skrynnik, for allegedly transferring some $140 million into Swiss bankExternal link accounts between 2007 and 2012. Another was an investigation into purchases of real estate in Switzerland by Artyom Chaika, the son of the Russian Prosecutor General Yury Chaika, who was also part of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s close circle. Both cases were dropped due to a lack of evidence.

Lauber was never formally investigated for these cases.

Vincenz Schnell was responsible for investigating Russian cases, including the Magnitsky case. The Russian media outlet Novaya Gazeta has referred to him as the “Counselor to the (Russian) Federal Prosecutor”. He also had ties with the former Deputy Prosecutor General of Russia, Saak Karapetyan –who has since died in a plane crash – and the infamous lawyer Natalya Veselnitskaya, who was interrogated over possible Russian interference in the 2014 US election, and indicted by the US Department of Justice for “obstruction of justice”. External link

In 2017, the Swiss Federal Police filed a complaint against Schnell for “corruption” and other crimes for an unofficial trip to Russia in 2016. The accusations were downgraded to “taking advantages in the form of hunting trips”. External link

When contacted through his lawyer, Schnell did not reply to our interview request.

“There’s quite a lot of evidence of significant intervention by the Russian secret services and the prosecutor’s office in the investigation of money laundering in the case Magnitsky in Switzerland,” says Shumanov, the head of Transparency International Russia.

“We had doubts that the Swiss authorities were reviewing this story impartially. And it is obvious that the Magnitsky investigation should have been a significant phenomenon for Switzerland. It makes you think, in fact, that there is no political will in Switzerland to investigate such crimes,” he adds.

Lauber resigned in 2020 “out of respect for Swiss democratic institutions” after being impeached by two parliamentary committees. The impeachment came after he was involved in other high-profile cases, including an unrecorded meeting with Gianni Infantino, the head of the world football federation, FIFA.

In 2023, the criminal proceedings relating to the Infantino meeting were dropped.

The two parliamentary committees said Lauber was suspected of “abuse of office, violating confidentiality and favouritism”.

“Due to official secrecy, to which I still have to adhere, I cannot provide you with any information in response to your questions. I do not comment on conjectures, false accusations, and rumors circulated by the media. Likewise, I do not comment on the assessments of alleged experts who give opinions without knowledge of the files,” wrote former attorney general Lauber in an emailed statement to SWI communicated through his lawyer.

To be continued…

Meanwhile, in 2020 an official investigation into Lauber initiated by the OAG’s supervisory body said that he had “seriously violated his official and legal duties”, and through his conduct had “damaged the reputation of the Office of the Federal Prosecutor of Switzerland”.

Following Lauber’s resignation, Swiss parliamentarians considered reforms of the OAG and commissioned two reports. One of the options considered was curtailing the prosecutor’s powers.

“Work by the committee in charge of the Federal Tribunals and the OAG are secret. Nonetheless work on supervision and sanctions is ongoing. Currently, there has been a change in management with a clear will of the prosecutor to rigorously follow the law,” says Carlo Sommaruga, a member of the Swiss parliament who sits on the committee responsible for overseeing the Swiss legal system.

In June 2023, the OAG’s supervisory body said that between 2016 and 2020, case management by the office was “deficient and obsolete”. They said an analysis of 6,400 non-active cases revealed that three out of four proceedings were closed without the defendants having been heard. In the case of criminal investigations, a hearing was held in only one in ten proceedings.

Epilogue

“[Schnell] behaved worse than a Russian public interrogator under Stalin, which would have been more correct and polite to me that he was,” Andreas Gross says of his interrogation by Schnell.

“The only difference is that in Russia I would be thrown into prison or in a Gulag in the Far-East. Schnell could not do that,” Gross adds. Gross, now retired, remembers feeling “totally helpless” at the time.

As a member of the Council of Europe until 2016, Gross monitored Russia from 2008 to 2014. He was also a rapporteur on human rights in Chechnya between 2004 and 2007. He personally met Putin in 2000 and observed about half a dozen Russian elections. Tasked with writing a report on the impunity of those responsible for Magnitsky’s death, he travelled to Moscow several times between 2011 and 2013.

Gross met Lauber in Bern only once while he was preparing his report on Sergei Magnitsky’s death. “I asked him then if he could imagine that in Russia the tax authorities had stolen the tax money themselves. Lauber said he was aware of this.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds/gw/livm/vdv

This story was amended on July 23, 2024 to clarify that Denis Katsyv held money at Edmond de Rothschild bank, not Rothschild bank as previously written.

This article was corrected on July 5 to specify that : the OAG claimed that CHF4 million that were previously frozen would be confiscated while the rest could not be traced back to the Russian budget. A previous version of the article stated that the rest “could be traced back to the Russian budget”.

This article was amended on November 14, 2024. An earlier version described an encounter between Andreas Gross and a person who claimed to be Vinzenz Schnell’s sister. This passage was removed as Vinzenz Schnell assures SWI that he does not have a sister. SWI does not have the means to verify this claim. This clarification does not alter the content of the article.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.