How two years of war in Ukraine have marked Switzerland

Switzerland, a country which had long managed to side-step conflicts, has not been left unruffled by the war in Ukraine. Two years after the Russian attack, how has the Alpine nation been affected?

Neutrality: debates about definitions or a real shift?

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the Swiss response sparked a flurry of debates about its traditional nonpartisan stance. After initial hesitation, Bern joined European Union sanctions against Moscow, a move seen by some – and not justExternal link in Russia – as a decisive break with the past. It also came as neutral states, especially in Europe, came under pressure to adapt to the new situation and “join the real worldExternal link”. Finland and Sweden have since shelved neutrality by joining NATO (see below).

Two years on, the debate has subsided. Despite taking over EU sanctions, and finding a way to sell tanks to Germany, Switzerland remains attached to a policy it has followed since 1815. Over 90% of the population backed neutrality in a 2023 poll, and at the political level debates about “active”, “integral” or “cooperative” variants never lose sight of the all-important word “neutrality” itself. The population may even get to choose their preferred definition: a people’s initiative to inscribe “perpetual and armed neutrality” in the constitution has until May this year to gather the 100,000 signatures for a public vote.

More

What does the future hold for Swiss neutrality?

The army: getting nearer to NATO, boosting its budget

Swiss neutrality naturally goes hand in hand with an aversion to military alliances. But the debate has been shifting here too: public appetite for NATO membership – which would mean the signing of a collective defence pact – grew by 12 percentage points over the past decade, to 31%. Over half of the public now approves of closer cooperation with the alliance. And faced by criticism of military freeloading (US Ambassador in Bern Scott Miller called Switzerland the “hole in the NATO donut”), the government recently announced such closer cooperation – though politicians are keen to set limits on how far it could go.

NATO or not, the past two years have also boosted the profile of the Swiss army in general. After decades in which it was allegedly “pared back to the bone” – the words of Defence Minister Viola Amherd – the Russian attack spurred a decision to boost military spending to 1% of GDP before 2035. The army is also planning flashy training exercises such as landing fighter jets on the country’s biggest motorway; such images haven’t been seen since the Cold War. And while recent weeks have been marked by media reports of miscalculations in the army’s budget, what’s clear is that defence (spending) is back on the agenda.

More

‘There’s a natural interest in cooperation between NATO and Switzerland’

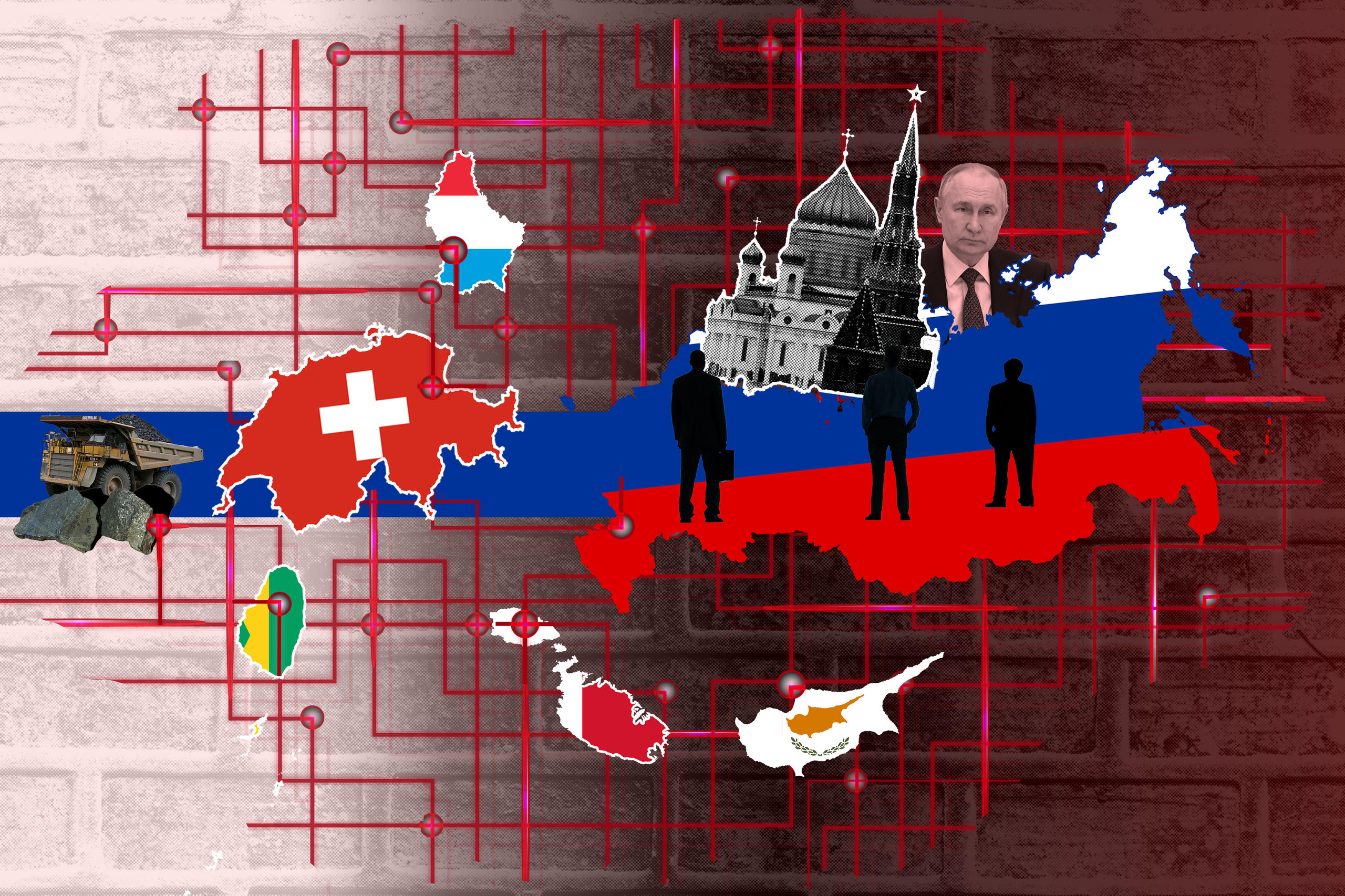

Sanctions: still closing loopholes

Since taking over the first EU sanctions package on February 28, 2022, Switzerland has followed suit a further 11 times – most recently with measures targeting the Russian diamonds and liquefied gas sectors. The sanctions now affect various important Swiss industries, notably banking and commodities trading. Authorities meanwhile say that some CHF7.7 billion ($8.8 billion) in Russian-owned financial assets were frozen in Switzerland by December 2023 – a sizeable figure by European comparison, but a fraction of the estimated CHF150 billion stashed away by wealthy Russians in the Alpine nation.

Indeed, taking over the sanctions did not prevent criticism of their implementation. US pressure on Switzerland to look harder for Russian assets culminated in April 2023 with a request by G7 nations that Switzerland join an international sanctions taskforce – a request which was politely declined. Such criticism has since “mostly disappeared”, a Swiss economics ministry official told Reuters this week, and other nations now apparently recognise that Switzerland takes the sanctions seriously. Just in time for the two-year anniversary of the war, the ministry also said it had set up a specialist team to investigate and enforce the sanctions.

More

Switzerland’s secrecy blind spot hinders sanctions enforcement

Mediation: hopes for a peace summit

Another aspect of Swiss foreign policy which has come under pressure in the past two years is the country’s role as mediator and protecting power. In August 2022 Russia rejected an offer to represent its interests in Ukraine, saying Switzerland was no longer neutral. Since then, diplomatic efforts have been confined to the hosting of a Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano in July 2022 (which had been planned before the war) and a recent gathering of national security advisers on the margins of this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos.

A visit to Bern last month by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky resulted in news: Switzerland intends to host a high-level peace summit on the conflict. Details are scarce about the event, which is mooted for Geneva, but many have noted that it will be hobbled by the fact that one of the warring parties is unlikely to attend; Russia sees the conference as too closely aligned with Ukrainian interests. As such, the goal will be to build as much international consensus as possible around what a future peace could look like.

Switzerland is thus keen to attract as many non-European powers as possible; Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis notably lobbied his Chinese counterpart during a recent visit to Beijing, but without obvious success.

More

‘Switzerland has lost its opportunity to mediate for peace in Ukraine’

Humanitarian aid: receiving refugees, sending help

The UN estimates that 6.3 million people have fled Ukraine since February 2022. For its part, Switzerland has seen some 86,000 applications for a special “S” status which it introduced for the first time ever in March 2022. The status, which enables refugees to work and to benefit from integration measures such as language classes, will remain valid until “the security situation allows for people to return”, the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) says. In 2024 SEM expects a further 25,000 applicants. Of those who have come, around two-thirds are women, many of them with children, SEM recently said. Some 22% have managed to find work.

Measures linked to the S status also make up the lion’s share of Swiss financial help for Ukraine since the war started: between February 2022 and July 2023 it accounted for four-fifths of the CHF2.03 billion in aid, the government has said. The rest of this money is flowing into Ukraine, as humanitarian funding or for repair works. Fire engines and even trams have been sent. In the longer term, Cassis is also determined to make a big contribution to the rebuilding of Ukraine: media reports in December mentioned the figure of CHF6 billion over a decade. However, as the Swiss budget heads for a deficit, Cassis and his colleagues face tough decisions about where this money would come from.

More

When Switzerland opened its doors to Ukraine

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.