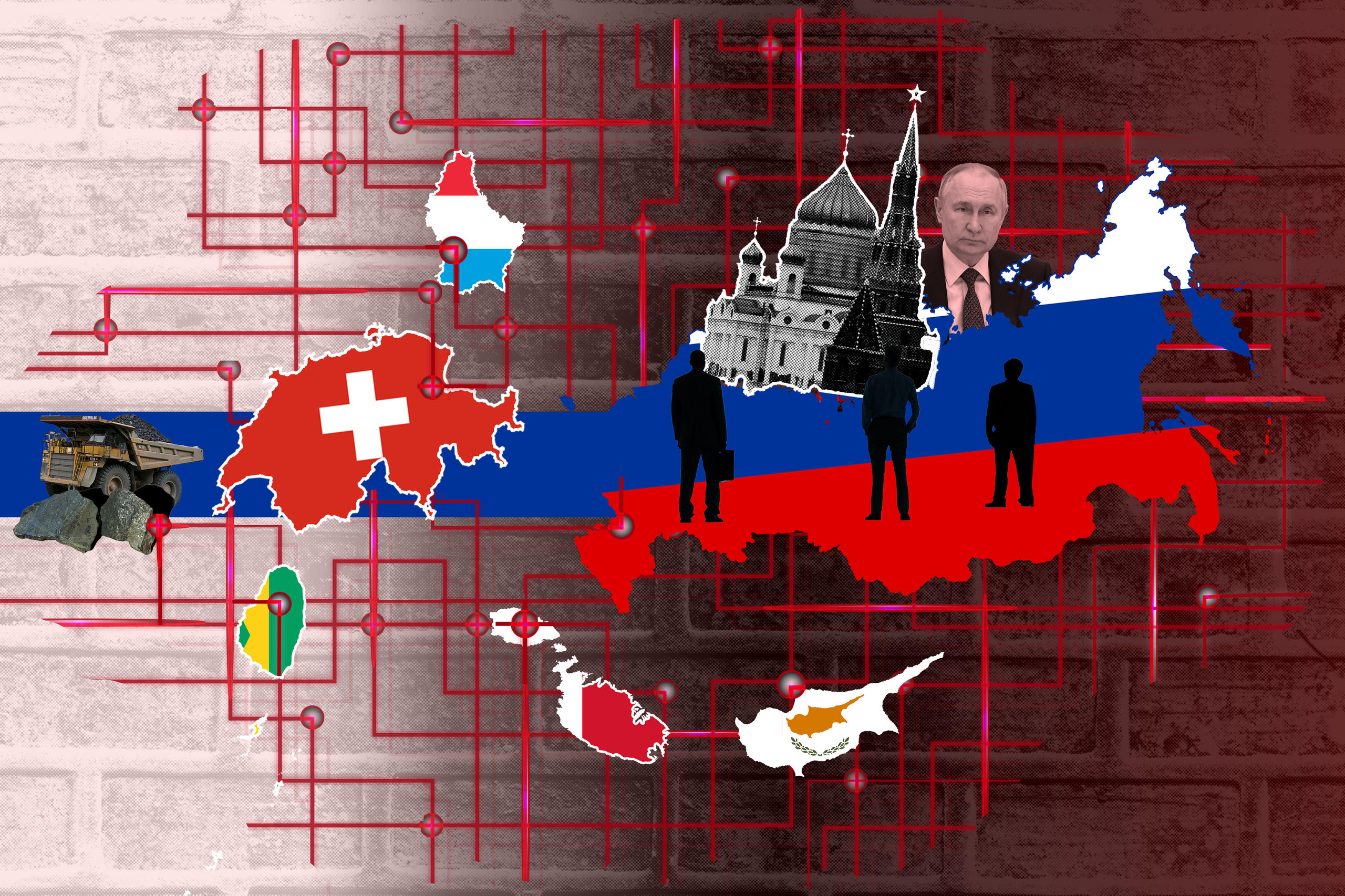

Russian nuclear giant Rosatom’s subsidiary thrives in Switzerland

Spared from sanctions, Rosatom in Switzerland continues to prosper. Some of Switzerland’s atomic power stations are powered by its uranium, and one of its subsidiaries is registered in the central canton of Zug.

+ Get the most important news from Switzerland in your inbox

Russian State Atomiс Energy Corporation Rosatom is one of the world leaders in the nuclear market. The Russian conglomerate has a 36% share of the global market. In Europe, nearly a quarter of the natural uranium consumed comes from Rosatom, according to Teva Meyer, lecturer in geopolitics at the University of Haute-Alsace.

“The Russian state-owned company is a fundamental partner for the continent,” adds the civil nuclear expert. Alternative supplies are rare.

This dependence on Russian nuclear power has led to the creation of a host of subsidiaries. In total, Rosatom has more than 450 subsidiaries around the world. Among them is Internexco Sàrl. Based in Zug for nine years, this company specialises in the marketing of oil, nuclear and gas products. This spring, it amended its articles of association to add fertiliser and cereals to the list of goods it negotiates and markets.

More

Mark Pieth: ‘Switzerland muddles on with sanctions’

Internexco won a contract to supply uranium to the Angra nuclear power station in Brazil, six months after the start of the war in Ukraine, in August 2022. This is strongly criticised by some people in Switzerland.

Florian Kasser, an expert on nuclear issues at Greenpeace Switzerland, told Swiss public television RTS: “Rosatom is directly involved in the invasion of Ukraine. Its engineers are in charge of the Zaporijia power station. Doing business with Rosatom or hosting a Rosatom branch ultimately means supporting Russia’s attack on Ukraine.”

The Washington Post also revealed last year that Rosatom was supplying equipment and raw materials to the Russian defence establishment.

A dive into the commercial registers shows that the Zug structure is not the only one. A Rosatom subsidiary based in Mendrisio in Ticino, which ceased trading at the end of August 2024, “specialised in wrought iron equipment, large industrial equipment”, explains Florian Kasser.

Another company, a Rosatom subsidiary currently in liquidation, was registered in Zug for nine years: Universum Metal Cart. Over the years, the company has changed its name.

Among them: Uranium One Trading. This makes it possible to trace the origins of Uranium One, a Canadian mining company that has been in Russian hands since 2009 and is currently active in the Sahel region.

Members of Internexco’s board of directors also held similar positions at Universum Metal Cart. These affiliations illustrate the complexity of Rosatom’s interconnected networks and prove the entanglement between these entities.

More

Switzerland’s secrecy blind spot hinders sanctions enforcement

Sanctions against Russia have been increasing since February 2022. But the nuclear industry remains spared to some extent. Last May, the United States imposed an embargo on imports of Russian enriched uranium. Europe and Switzerland are not following the same path and are not imposing any sanctions.

“In theory, Switzerland could adopt unilateral sanctions on Russian nuclear power,” confirms Robert Bachmann, a commodities expert at Public Eye, before qualifying: “It is highly unlikely that the federal government would take such measures. The reason for this? The dependence of nuclear power stations on Russia. In Switzerland, the uranium used in the two reactors at Beznau is Russian; and at Leibstadt, some of it is.

For Greenpeace, the road to independence from Russian nuclear power lies in sanctions targeting Rosatom’s branches. “This is where we could start to sanction Rosatom without directly affecting its uranium deliveries”. With this strategy, Switzerland could increase the diplomatic pressure on Moscow.

“There are two ways of breaking our dependence on Rosatom,” confirms Teva Meyer. “Either we stop using nuclear power or we try to develop industrial capacities in Europe, the United States or Japan […] These are decisions that need to be taken now. Otherwise, we’ll be in the same situation in ten years‘ time.”

Translated from French by DeepL/jdp

This news story has been written and carefully fact-checked by an external editorial team. At SWI swissinfo.ch we select the most relevant news for an international audience and use automatic translation tools such as DeepL to translate it into English. Providing you with automatically translated news gives us the time to write more in-depth articles.

If you want to know more about how we work, have a look here, if you want to learn more about how we use technology, click here, and if you have feedback on this news story please write to english@swissinfo.ch.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.