Switzerland is not neutral on the death penalty

Switzerland has made it a stated goal to abolish the death penalty worldwide. Its defenders, on the other hand, insist on national sovereignty and wish to distance themselves from so-called Western values.

By 2025, Switzerland aimed to achieve a world without the death penalty. This ambitious goal was set by the country 11 years ago. “As long as the death penalty exists, we shall continue to fight against it,” said Didier Burkhalter, then foreign Minister, when the goal was set in 2013.

The goal has not been reached, but the trend has long been toward abolition. Today, only a hard core of around 20 countries regularly carry out executions. The vast majority of countries have abolished or suspended the death penalty. This development is a historical breakthrough.

Yet we are still far from a world without executions. China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the US still regularly execute people. Amnesty International reported 1,153 known executions in 2023 – an increase of 31% from the previous year and the highest number in a decade. The true figure is believed to be much higher.

States that still maintain and implement the death penalty often stress the principle of national sovereignty. International law does not prohibit the death penalty per se. Therefore, they claim it is their right to carry it out. Many of these states portray its abolition as a Western concern that is incompatible with their values and legal systems. Ultimately, they argue that the West seeks to impose its values and reinforce its hegemony – a claim that can be found in various forms in international politics.

“Every person has the right to life. The death penalty is prohibited.” This principle has been enshrined in the Swiss Federal ConstitutionExternal link since 1999, and it is also guides the country’s foreign policy. The principle that the death penalty is categorically and under all circumstances prohibited has been a foreign policy priority since 1982. The last executions in Switzerland took place in 1944. Paradoxically, the death penalty remained an option in Swiss military law until 1992. This illustrates the complicated situation surrounding capital punishment.

Abolishing the death penalty: not just a Western concern

In any case, it was civil society players rather than politicians who spearheaded the campaign against the death penalty in the second half of the 20th century.

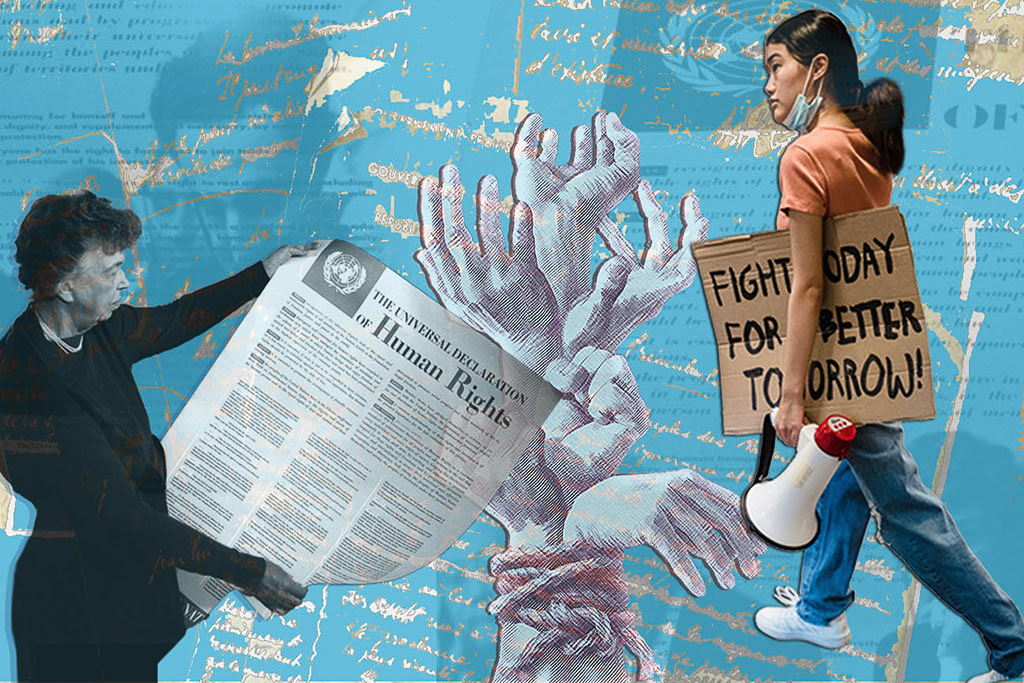

After the atrocities of the Second World War, the United Nations was established, and with it the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which defined the right to life as a fundamental principle and prerequisite for the prohibition of the death penalty. It was primarily transnational civil society networks that fuelled the abolitionist movement. Among these was Amnesty International, which became one of the leading voices on the issue internationally.

More

How the Universal Declaration of Human Rights aimed to change the world

Chiara Sangiorgio coordinates Amnesty InternationaExternal linkl’sExternal link global campaign against the death penalty from London. After the Second World War, she explains, only a handful of countries did not have the death penalty. Almost all were in Latin America, where capital punishment was mainly associated with colonial repression. Its abolition was thus part of national emancipation. The first modern state to get rid of the death penalty was Venezuela in 1864. “We should bear in mind that the movement against the death penalty is not a purely Western concern,” Sangiorgio says.

The democratisation wave of the 20th century is seen as an important factor in the decline of capital punishment worldwide. The US remains a notable exception among democracies, although fewer and fewer people are being executed in this country (24 people in 2023, all by lethal injection).

The death penalty is widely considered an instrument of repression, social control and the suppression of political opposition. Moreover, there are “no scientific studies that prove that it has a positive impact on crime prevention and security or that it is more effective than other severe punishments”, the Swiss foreign ministry wrote in its 2024–2027 action plan for the universal abolition of the death penaltyExternal link.

National sovereignty versus human rights

Nonetheless, states that retain the death penalty often argue that they are tough on criminals. They want to signal to their own populations that the state is “tough on crime” and intends to punish the guilty, according to Aurélie Plaçais, director of the World Coalition Against the Death PenaltyExternal link (WCADP). “Ultimately, it is a simple answer to complex problems and crime,” she says. For context, in 2022, 37% of executions carried out worldwide were for drug-related offences.

The WCADP is an international umbrella organisationExternal link based in France that campaigns for the abolition of the death penalty worldwide and unites 185 organisations. Many of its members are persecuted in their own countries for their activism.

The external communication strategy of those states that retain the death penalty follows a different line, notes Plaçais. Internationally, states do not emphasise crime control but insist on their sovereignty and that international law does not prohibit the death penalty. Each state thus has the right to impose it, as it falls within its national sovereignty.

Noticeably, this is argument is often raised by states in their votes within the UN framework. They complain that the diversity of legal and political systems is not respected, thus jeopardising the equality of states. Ultimately, they say, it is all about imposing a specific world order and particular values. This is a clear criticism of the West, which in their eyes dominates the multilateral system. They explicitly do not recognise the universality of human rights.

The countries with the most executions are quite varied. First there is China, a single-party communist state that imposes the death penalty for a wide range of offences. Many of the details are unclear as there is little official communication on the matter and the number of executions is unknown. “We assume that thousands of executions are carried out each year,” says Plaçais.

Next comes Iran, a theocratic-authoritarian system that has used the death penalty, sometimes massively, as an instrument of repression since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. More recently, the country turned to capital punishment to stamp out the protests that followed the 2022 murder of Jina Mahsa Amini. Iran also carries out the death penalty for drug offences and religious offences – a trend also observed in absolute monarchy Saudi Arabia. The US, meanwhile, is one of the few democracies in the world that still carries out executions, although the numbers have been declining for some time and more and more states are banning or suspending this practice.

“What all the countries have in common is a high degree of state violence,” says Plaçais. They conduct repression and discriminatory policies at home, as well as military conflicts abroad.

Between PR and true abolitionism

Then there are countries like Saudi Arabia. It projects an image of modernisation to the outside world, whereas the number of executions has soared. Saudi Arabia executed 172 people in 2023. “The situation is worse than ever,” says Taha Alhajj, legal director of the European Saudi Organisation for Human RightsExternal link (ESOHR).

Much has changed since Mohammed bin Salman became the strong man in the kingdom. Social rules have been softened, religion is taking a back seat, and the country is opening up to tourism. For Alhajj, however, this is pure PR: “Sport, music, influencers – Saudi Arabia is investing billions to give itself a clean image. Yet never before have so many people been executed.”

The kingdom is flouting basic rights, according to Alhajj. For instance, by sentencing people without legal representation and executing minors. The catalogue of offences that can incur capital punishment is also wider than ever before. People are now also being executed for political or religious reasons.

“On the international stage, Saudi Arabia plays lips service to human rights,” he concludes. “This is pure manipulation and lies.”

ESOHR knows from experience what this means for civil society. The organisation’s founder was persecuted and imprisoned, and all the members had to flee abroad. “The penalties threatened are draconian; there are no longer any human rights activists in the country who stand up against the death penalty,” says Alhajj.

More executions are likely

What happens next? The human rights activists Sangiorgio and Plaçais see a clear trend: the number of countries with the death penalty will continue to drop. “Several states are currently considering draft legislation to abolish it,” points out Plaçais.

However, the number of executions has increased in recent years, including in Saudi Arabia. While both expect to see fewer countries with the death penalty, they also predict a higher number of executions in the countries that keep it.

And, presumably, these states will continue their efforts to obfuscate the issue. In 2002, the Chinese government stated that the death penalty’s “ultimate worldwide abolition” will be the “inevitable consequence of historical development”.

Yet China remains the country with the highest number of death sentences carried out – by far.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl. Adapted from German by Julia Bassam/ds

More

Our weekly newsletter on geopolitics

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.