Why Afghanistan’s reserves remain stuck in Switzerland

Afghan state assets equivalent to a quarter of the country’s GDP sit frozen in a Swiss bank account. They are managed by a Geneva-based fund that has not released a single dollar since it was set up over two years ago. The money could be a financial lifeline for the Afghan economy.

When the Taliban marched into the Afghan capital Kabul on August 15, 2021, Masuda Sultan knew it would be bad news, she just didn’t realise how bad.

First, her bank in the United States refused to transfer money to Afghanistan that was funding her NGO, Women for Afghan Women, she was running at the time. Soon after, the country’s teachers’ union sought help from Sultan and other women’s rights advocates to lobby the World Bank to unfreeze aid from its Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) and disburse the salaries of 220,000 female educators who had been unpaid for months. Then, Sultan learned that Afghanistan’s central bank was no longer able to access billions of dollars of its reserves, a vital source of money to help keep the economy running and prevent runaway inflation.

“If you think about this money, it’s literally the wealth of the poor in one of the poorest countries on earth,” she told SWI swissinfo.ch, referring to the reserves. “It’s one of the reasons I really wanted to get behind this issue of the frozen assets, even though it could be seen as controversial in some quarters.”

The country’s dire situation galvanised Sultan into action. She helped set up the Unfreeze Afghanistan campaign in November 2021 to pressure the US government and lenders like the World Bank that had suspended aid to release cash so that Afghan teachers could be paid and essential public services maintained.

US President Joe Biden froze some $7 billion (CHF6.4 billion) of assets held in the US by Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB), the central bank, when the Taliban took power. Half of the money was subsequently put into a trust fund, the Afghan Fund, to support humanitarian assistance in the country while ensuring the new leaders had no access to the cash. The other $3.5 billion was held back to fund potential compensation in an ongoing court case against the Taliban brought by the families of victims of the September 11, 2001, attacks in the US.

More

How a portion of Afghanistan’s foreign reserves ended up in Geneva

The Afghan Fund is based in Geneva and has a mandate to handle the assets, which are now worth $3.9 billion, but it has not disbursed any of the money since it was established in September 2022. The board of trustees, comprising two Afghan experts, a US Treasury official and a Swiss diplomat, has not publicly disclosed how it intends to use the funds or whether they will be retained in Switzerland. But as humanitarian donors grow tired of shipping cash to Afghanistan, their lack of action is turning into a question of life and death for the people of the crisis-hit country.

Engagement or isolation

Born in Afghanistan in 1978, Masuda Sultan fled to the US with her family in 1983 to escape the decade-long Soviet war in Afghanistan. She became a women’s rights activist after fightingExternal link her way out of an arranged marriage in her community of Afghan-Americans in New York. Since childhood, Sultan said she was convinced that poverty and war were Afghanistan’s main problems. Aiming to find solutions, she studied economics and earned a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard University. In 2001, she co-founded one of the largest women’s organisations in Afghanistan, Women for Afghan Women, a shelter for women, and went on to advise the finance ministry of the US-backed Afghan government from 2007 to 2008.

As the Taliban regained power in province after province in 2021, Sultan faced the same dilemma the Afghan Fund is grappling with now: engagement or isolation. She chose to keep up her work in the country and started campaigningExternal link for the release of the frozen assets. She helped foundExternal link the organisation Unfreeze Afghanistan, which urgedExternal link the US court hearing the case of the 9/11 families to preserve the assets of the Afghan central bank for the people of Afghanistan, and demandedExternal link the assets held in Switzerland be returned.

“We all had put in our work over 20 years to counter the Taliban in every way we could,” Sultan said. “But then what do you do? Do you isolate them in the hopes that someone will topple them?”

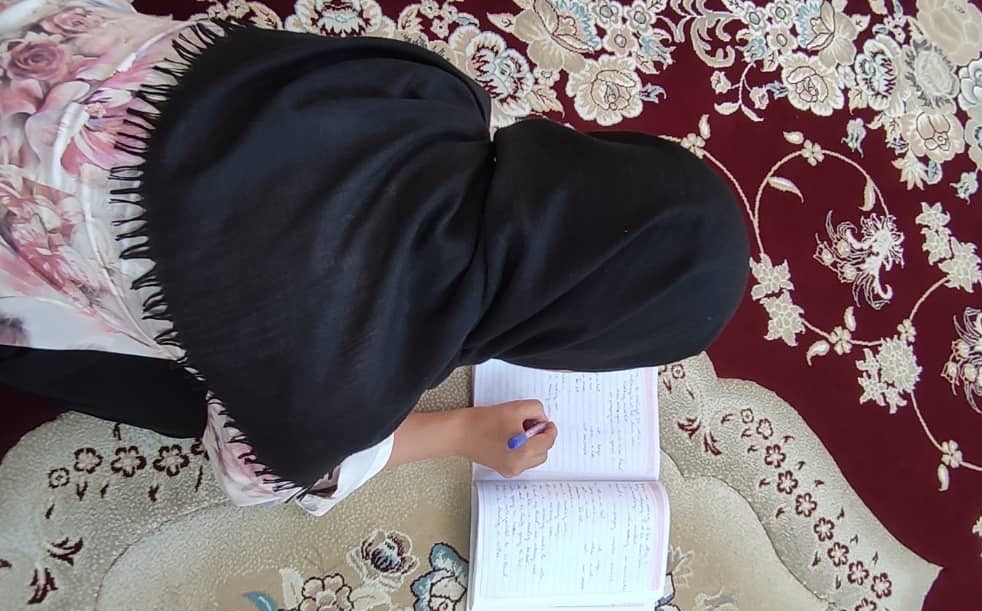

Given that the Taliban target women and girls with a repression system that UN experts labelExternal link gender apartheid, Sultan’s stance may seem surprising. But her point is that not engaging with the de-facto rulers inflicts even more pain on ordinary civilians.

“Afghanistan is suffering greatly from problems we can solve,” Sultan said. “While we can’t control what the Taliban do, we can do whatever is possible to help the people of Afghanistan. So we should do at least that much.”

Liquidity crisis

The US decision to freeze DAB’s assets, along with a sudden drop in international development aid, hit Afghanistan’s economy badly. The central bank could no longer supply commercial banks with cash. Afghans rushed to retrieve their money and found ATMs empty. The liquidity crisis became so grave that in December 2021 the UN started shippingExternal link physical dollar notes to Kabul to fund emergency aid programmes.

Around $4 billion in cash has reachedExternal link Afghanistan by plane since the start of the UN programme, helping to stabiliseExternal link the Afghan economy, albeit at a precariousExternal link level. Now this lifeline is slipping awayExternal link as international donors shift their focus to crises in other parts of the world and scale back their humanitarian aid to the country. That’s despite estimates by the World Bank in 2023 that reducingExternal link cash shipments by 25% would lead to a drop in GDP that could force large numbers of families into drastic measures to survive, including selling daughters into child marriages.

A funding shortfall forced the World Food Programme to slashExternal link its emergency assistance to Afghanistan in 2023, cutting food rations and withdrawing support from ten million people. In 2024, less than half the UN’s humanitarian appeal of $3.1 billion for the year was met, leavingExternal link a funding gap of $1.6 billion. The UN expectsExternal link that almost 15 million people – over a third of Afghanistan’s population – will suffer from acute food insecurity through March 2025.

“We cannot be dependent on aid and rely on the cash shipments forever,” said Sulaiman Bin Shah, who served as Afghanistan’s deputy minister of industry and commerce until the Taliban’s takeover and now leads a business consultancy in Kabul. “We really need to have the investor confidence back, the banking confidence back in the country. But the necessary financial guarantees can only come if the central bank functions like a normal central bank, and for that it needs assets.”

In a letter to the UN’s negotiators dealing with Afghanistan in June 2024, seen by SWI swissinfo.ch, Bin Shah called for the recapitalisation of the central bank using the $3.5 billion held in Switzerland. The letter, co-signed by several business and civil society leaders based in Afghanistan, also proposed allowing an internationally recognised audit firm to monitor each payment made by the central bank, and to use the interest earned on the reserves to facilitate international trade and investment in the country.

So far, the Afghan Fund has remained silent on its intentions and whether it plans to return assets to DAB anytime soon.

“I think that part of the reason they have not spoken is that it’s still unclear what role the fund will play,” said Graeme Smith, an analyst at the International Crisis Group, a thinktank. The Taliban has refused to acknowledge the Afghan Fund’s legitimacy and is demanding the immediate return of the assets to the central bank, he said. But the fund was designed to ensure a slow process and an American veto over the money aiming to prevent headlines about the Taliban swimming in US cash. “One might say that the fund is working as intended, to keep the problem out of the news.”

Politics over people

Shah Mohammad Mehrabi, one of the four board members of the Afghan Fund and a professor of economics at Montgomery College in the US, agreed to be interviewed by SWI swissinfo.ch, although he made clear that he was speaking in a personal capacity and not on behalf of the board of trustees, which has to agree on decisions unanimously. Mehrabi, who is also a member of the governing body of Afghanistan’s central bank, has in the past made the caseExternal link for returning funds via duly monitored tranches to stabilise the Afghan economy.

This has not happened so far because neither the US nor any other state has recognised the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, Mehrabi said. “That is the primary reason why there has not been much movement on our side.”

It has also taken time to set up the organisation and put the required structures and compliance procedures in place, he said. The board first had to establish a robust governing structure. It created a legal entity in Switzerland, adopted an investment strategy, developed risk management policies, clarified how to verify vendors, and came up with compliance procedures for issues such as money laundering and terrorist financing, he said.

Now the fund is technically in a position to make targeted disbursements, according to Mehrabi. The board agreed that no money will be used for humanitarian aid, he said, as the reserves are meant to be used to stabilise prices and exchange rates. With UN cash shipments dwindling, a scarcity of dollars could drive up inflation and make such injections necessary.

But there are significant obstacles to overcome before the assets can be unfrozen, which goes back to the political question of recognition. For the board, it is critical that the central bank prevent any funds from being used for money laundering or financing terrorism, Mehrabi said. To ensure this, some kind of engagement and technical training for central bank staff is necessary, but the international isolation of the Taliban has hampered such steps, he said.

A stand-off between the Taliban and the US over the appointment of the head of DAB is also holding up the return of the frozen funds. The regime appointed an official subject to US and UN sanctions as acting governor back in 2021 and in July replaced him with another sanctioned official, Noor Ahmad Agha.

“I do think the Taliban need to change,” Masuda Sultan said. She has grown frustrated with the leadership’s refusal to agree to international demands that the rights of women be protected and with its appointment of Agha, actions that are perpetuating the suffering of the Afghan people.

“The problem is political at its core,” she said about the frozen assets in Switzerland, circling back to the fundamental choice between engagement or isolation. “Unless we solve the underlying political questions, there’s no way that this money is going to be put to use.”

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis ReportingExternal link.

More

Our weekly newsletter on foreign affairs

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.