Why legal medicine in Africa needs a boost

Forensic science is critical in the search for justice and the fight against impunity. Yet many countries in Africa have few practising forensic pathologists. One medical institute in Switzerland is working to change this.

On the days when Tidianie Mogue has an autopsy to perform, the medical examiner pulls on her protective gear – disposable gown, gloves, cap and shoe covers. The Central Hospital of Yaoundé where she works may be the largest in Cameroon, but it doesn’t always have the funds to cover the cost of these basic tools of the trade.

“Each examiner has to fight for the material they need,” says Mogue in a video call with SWI swissinfo.ch. “Sometimes we ask the families [of the deceased] to make a contribution so we can buy gloves or scalpels.”

The challenges don’t end there: Mogue and the three other forensic pathologists at the hospital make do with rudimentary autopsy rooms, in some cases consisting of just a table and a water tap.

For years the doctors have solicited more resources for their work. “But nothing changes,” says Mogue, despite their sizeable caseload. By her estimates, only around eight forensic doctors are employed by the state for all of Cameroon (population 27 million). Serious crimes there range from the killing of civilians by armed forces in the country’s northwest to the murder of journalists and mob attacks against members of the LGBTQ+ community.

‘The body is the most important piece of evidence’

Cameroon is one of several countries in Africa struggling with the lack of expertise in legal medicine, which encompasses forensic pathology – the investigation of suspicious deaths through post-mortem examination. In Burundi, legal medicine is “virtually non-existent”, says Bamtama Mossi, the director of Rumonge Regional Hospital in the country’s west.

“We have no forensic doctors specialising in this field anywhere in [Burundi],” he writes in an email. “When we are called on by the police or the courts to help look for evidence, we are limited to carrying out physical exams and additional tests, which do not help to shed light on the facts.”

Yet, with the country emerging from decades of conflict, says Mossi, legal medicine could play an important role: by identifying victims and establishing when and how they died, it could help “in the reconstruction of the truth about the wars”.

The place legal medicine occupies in the course of justice comes down to one thing, says Silke Grabherr, director of the University Centre of Legal Medicine Lausanne-Geneva (CURML): “The body is the most important piece of evidence.”

“If you’re not able to interpret this evidence – the cause and circumstances of the death, if it was natural or unnatural – then justice cannot be served.”

The CURML is one of seven legal medicine institutesExternal link that, together with so-called medical-officer systems, offer forensic pathology services in Switzerland (population 9 million). It’s now working with partners in Burundi to address the gap in expertise there.

The plan is, among other things, to bring Burundians to Geneva for a five-year training programme and eventually set up the country’s first legal medicine institute. The partners are seeking funding from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation for this ambitious 12-year project.

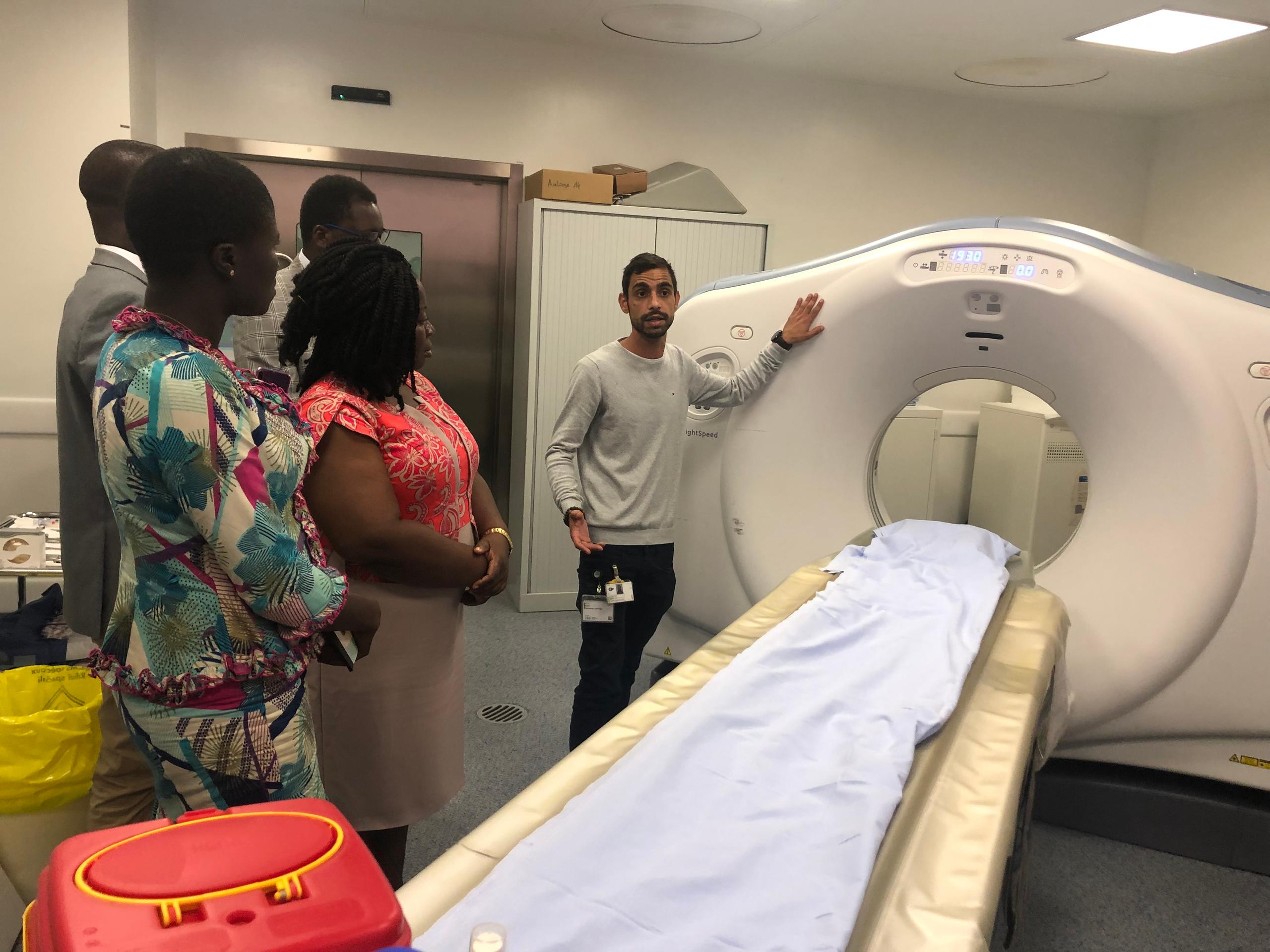

The idea for the project came after Mossi travelled to Switzerland in 2019 to take part in a six-month continuing education programmeExternal link at the CURML designed specifically for African practitioners. The course offers practical and theoretical knowledge in legal medicine, plus a chance to visit Swiss judicial institutions and do a short work placement.

At the heart of the course is a module on how to design a legal medicine service and find the funds for it, so students can get the ball rolling once they’re home.

“Ultimately we want each country in Africa to have structures in place to practise legal medicine,” says Ghislain Patrick Lessène, course coordinator and head of humanitarian legal medicine at the CURML. In his home country of the Central African Republic, only one state forensic pathologist is practising for six million inhabitants.

Lessène, who studied law in Geneva, learnt this after his father died in 2016 in the midst of a civil conflict – his family were denied an autopsy simply because no one was qualified to do it.

After his father’s death, Lessène had a direct hand in creating the continuing education programme, which is open mainly to professionals – judges, lawyers, police officers, administrators in justice or health ministries, and doctors. Each year between five and eight out of a class of about ten have their tuition fee of CHF6,500 ($7,180) covered by canton Geneva and the Swiss government.

Advocates for forensic expertise in Africa

The Swiss experts are not the only ones from outside the continent to provide support for forensics in Africa. The United Nations has plansExternal link to help the Democratic Republic of the Congo create a national strategy on legal medicine. Germany financedExternal link the renovation of a forensic medicine institute at the University of Cocody in Ivory Coast, which issues diplomasExternal link in legal medicine. And in Uganda, India has openedExternal link a campus of its National Forensics Science University.

Switzerland’s strength, says Grabherr, lies in the high level of expertise. Whereas some countries require just one or two years of training in forensic science to qualify as a medical examiner, in the Alpine country forensic doctors must study an additional five years on top of their medical degree. Switzerland also boasts advanced research and technology in this field, such as in forensic imaging, so doctors have cutting-edge knowledge to share.

The CURML alone has 12 units spanning among other specialties toxicology, forensic anthropology and forensic genetics. Critically, Swiss medical examiners receive a salary regardless of how many autopsies they do or what the results of these autopsies are. This system shields them from external pressure – unlike in places where pathologists are paid per case.

“This means that the more cases they accept, the better they are paid,” says Grabherr. “And sometimes this becomes an open door for corruption.”

In some countries, forensic pathologists can be pressured to drop an autopsy or change the conclusions of their report. In Cameroon, Mogue says she has sometimes been threatened and been offered bribes during her 11-year career.

“Someone who wants to introduce forensic pathology and legal medicine in their country is someone who wants to find the truth and fight corruption,” says Grabherr. “These people are very courageous.”

Big dreams for a full-scale legal medicine service

Building this expertise from the ground up, however, requires more than courage. Mossi talks of “huge challenges that stand in the way of introducing legal medicine in Burundi”.

More

‘Hope never dies’: Swiss help Mexicans tackle enforced disappearances

“We’re constantly talking to the government about the need for development in this area,” he writes. At the hospital in Rumonge, Mossi and his colleagues have not waited around and, with support from the CURML, are opening a forensic consultation unit for victims of violence.

Women suffering from gender-based violence are at the core of this new service – in Burundi, some 48% of women say they have experiencedExternal link physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner.

Health authorities are becoming increasingly receptive to the idea of building up local expertise, says Lessène. The country currently relies on Kenya for legal medicine.

Back in Cameroon, Mogue too is working on raising awareness about her profession. The medical examiner took part in the CURML course in 2021, travelling to Switzerland at her own expense. Since then, she and her colleagues have contemplated a new pathway for getting the well-equipped forensic service they all crave: requesting funding from the Swiss development agency. But first they need approval from the Cameroonian ministry of health, a complicated process with no guarantee of success, she says.

Mogue’s trip to Switzerland, though, has paid off in other ways.

“Despite the lack of resources, I was able to improve my daily practice,” she says. She shared learning material with the judicial police in Yaoundé, which has led to better collaboration with them.

Mogue and her colleagues are also now sending samples to the CURML for analysis for a few hundred francs per case. Sometimes families of the deceased will pay for the analysis themselves due to the lack of a budget or lab for toxicology – expertise that the doctor likes to envision as part of her dream legal medicine unit.

“This way, we would no longer have to send out samples for analysis, with the exception of the big ones,” says Mogue. “If we had just the minimum, that would already be a good thing.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.