‘Federal dealer’ on 20 years of heroin scheme

Armoured vans, armed guards and sealed containers are standard in transporting highly valuable commodities such as jewellery, gold – and diaphin. The brand name for pharmaceutically produced heroin, diaphin has been used to treat opioid addiction in a pioneering Swiss programme for 20 years.

It is for good reason that its transport involves extraordinary security measures. In 1994, when parliament and the Federal Health Office were still responsible for the procurement and delivery of heroin, it was actually stored for several months in an enormous bank vault directly next to the gold bars of the Swiss National Bank.

“I was a foreigner, yet one of the very few people who had access to this inner sanctum. Imagine that,” said the German-born head of the small Swiss firm that now produces and distributes diaphin on behalf of the Swiss government.

The costly delivery of diaphin to the approximately 20 heroin distribution centres takes place a few times a year. Armoured cars transport the contents in sealed containers that are fastened with handcuffs to armed guards. All this takes place under the watchful eyes of a security firm with specialised expertise in transporting gold to and from banks and servicing the elite Baselworld watch fair.

Once at the distribution centres, the stock is kept in safes linked by direct alarms to the police. The pharmaceutical firm stores the diaphin preparation at two secure and secret locations.

“That way, nothing can be diverted or go wrong,” said its CEO, who requested anonymity to protect employees and avoid criminal attention. The annual quantity of pharmaceutical heroin that it produces would be worth over CHF200 million ($225 million) on the black market.

Switzerland needs about 250 kilograms a year of diamorphine (the chemical name for heroin) to produce the medicine diaphin.

Production of this amount requires opium poppy acreage of 430,000 square metres, the equivalent of about 70 football pitches.

Areas under the control of United Nations authorities are in the order of approximately 880 square metres (the size of Lake Constance). From this about 450 tons of morphine are produced annually, 80% of which is processed into codeine (cough and pain medicine).

For pharmaceutical use, the capsules of the poppy plant are harvested by machine after they bloom, are dried, and pressed into pellets. Raw morphine is eluted from the pellets, which are refined into pure morphine through further processing, then into diamorphine.

In illegal production, the poppy capsules are scratched by hand. The sap that is gathered is raw opium. If this is treated with acetic acid and thinners are added, the result is street heroin. The amount of pure heroin in street heroin varies widely on the black market. Because the exact content of street heroin is not known, its consumption also carries the risk of life-threatening overdoses.

Fresh from Britain

Switzerland obtains its diamorphine – the chemical term for pure heroin – from Britain, which is one of the leading opiate manufacturers in the world and which has never banned the pharmaceutical product heroin. It is transported by plane to Switzerland.

Each time a shipment of diamorphine is imported, it has to receive consent from both the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) of the United Nations, and the Swiss federal narcotics control authorities.

Switzerland requires about 250 kilograms of diamorphine a year to treat its 1,500 heroin patients. It is processed into about 15,000 ampoules of 10 grams and 500,000 tablets of 0.2 grams.

Furthermore, the areas where the opium poppy is cultivated for pharmaceutical use must all be approved by the INCB and inspected by the UN. Huge opium poppy plantations are located in France and Tasmania, for example.

Swiss pioneers

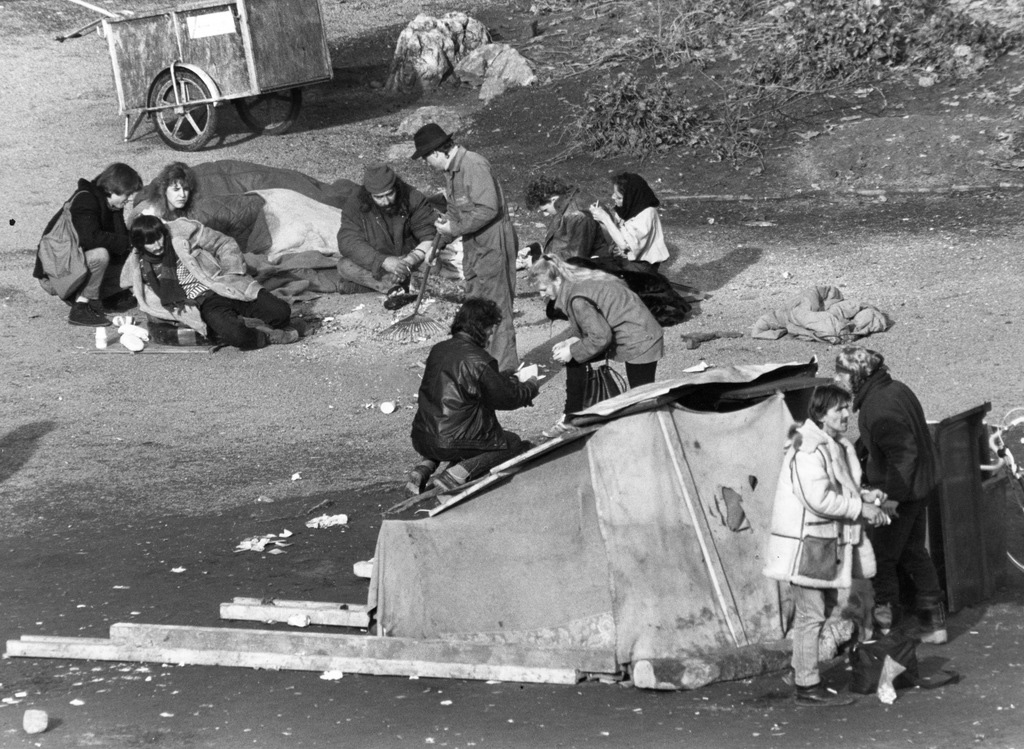

The abject drug misery that held sway at Zurich’s Platzspitz park, known popularly as “Needle Park”, spurred Switzerland in 1993 to opt for a pragmatic drug policy of distributing medically controlled heroin to therapy-resistant addicts.

The incorrect assumption that Switzerland wanted to “distribute heroin free of charge” provoked a widespread backlash in the country and abroad. Many other countries, and influential bodies such as the World Health Organization and the INCB, kept a close eye on the evolution of Switzerland’s ground-breaking experiment.

“We were the first country to try this therapeutic approach. It was very exciting but also extremely difficult,” remembers Paul Dietschy, who was head of the pharmaceutical division of the health office at the time.

“We didn’t have any suppliers, any experience with these kinds of pharmaceutical products, any research funds or any clinical studies with high dosage patients. Everything was virgin territory – and we had to be ready to go within a year.”

At the outset, even Dietschy had reservations about the wisdom of the new approach. In 1993, he was tasked with the procurement, pharmaceutical research and processing of pharmaceutical heroin together with his counterparts in the narcotics control division of the health office – a sort of “federal dealer”.

“If something had gone wrong, opponents of the policy would have had a field day and it probably would have meant the end of the heroin experiment,” he told swissinfo.ch.

“We never said where we imported it from, how we transported it or where we processed and stored it. Discretion was a top priority,” he recounted.

More

‘The heroin programme is a kind of prestige project’

French connection

The programme was dealt a major setback at the beginning. When Switzerland introduced the project at a press conference at the EU parliament in Strasburg, a journalist asked where the substance came from.

France, replied Ruth Dreifuss, Swiss health minister at the time.

“The next day, all the large French newspapers had stories on it. The responsible French minister, who had been in the dark about everything, was livid and stopped the shipments immediately,” Dietschy said.

“After this disaster, we had only enough supplies for ten days. I was running around in a stress trying to get some more. If we hadn’t found a new supplier, we would have had to discontinue the experiment.”

Following this bottle-neck, the possibility of growing opium poppies in Switzerland was explored.

“However, we had no experience with the cultivation and processing of these plants, so the planning would have taken years. Other obstacles were that it rains too much in Switzerland and that poppy cultivation requires a considerable amount of land,” he said.

More

Zurich’s infamous Needle Park

Hot potato

Besides all this, there was a processing problem to be dealt with. None of the large Swiss pharmaceutical companies wanted this hot potato associated with their firms.

“Because heroin had a terrible reputation – and still does – the pharmaceutical companies were worried about harming their reputation. It wouldn’t have been a lucrative niche product either. A further twist was that the sterilisation and processing of heroin to an injectable form proved more difficult than had been anticipated.”

About two years into the experiment, the production of diaphin was outsourced. The health office realised early on that it was too difficult to work within the ministry at the level of discretion demanded by such a sensitive task.

Diaphin was approved as a medicine in Switzerland in 2001. Later that year a small pharmaceutical firm received a licence to produce it.

In the mid-1990s, the project to provide opiate-assisted treatment for hardcore addicts was formally evaluated and the results appeared promising. The addicts were doing better in terms of health and social issues, and drug-related crime had decreased.

In the meantime, Dietschy’s initial misgivings about the project had given way to belief in its effectiveness.

Secret visits

By then he had a new position as Swiss delegate for drug issues at the UN and the European parliament, where he tried to convince other countries of the project’s merits.

Growing interest from foreign countries led to a long line of curious government representatives – state secretaries, health ministers and parliamentarians – making their way to Switzerland from the US, Germany, Norway and other European countries.

Dietschy gave them tours of the distribution centres and the former drug scene at the Platzspitz in Zurich.

“But always in total secrecy. We had to ensure that everything stayed strictly confidential and that no press came along,” he said.

Bad reputation

But despite the considerable interest in Switzerland’s cutting-edge programme, very few countries have tried to replicate it. Only the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark distribute heroin regularly to hardcore addicts.

Britain has some heroin distribution centres but no national programme. A Spanish effort has been put on ice, a victim of the financial crisis. Canada’s health minister recently halted prescription heroin for addicts, recommending acupuncture as an alternative.

Although diaphin was approved as a medicine in Switzerland years ago, heroin’s bad reputation remains so persistent that it cannot be distributed at pharmacies, the country’s normal dispersal point for medicine. Instead, special distribution centres have been set up solely for this purpose.

While the heroin treatment programme enjoys solid support among the Swiss, it nevertheless remains a thorn in the side of its opponents. Most other European countries continue to view it sceptically.

The CEO of the firm that produces diaphin finds it a pity that addicted patients are still not taken seriously as sick people. Paul Dietschy agrees.

“No one would even think of denying a heavily addicted smoker with lung disease the necessary medication.”

(Translated from German by Kathleen Peters)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.