Green hydrogen vies for centre stage in climate change fight

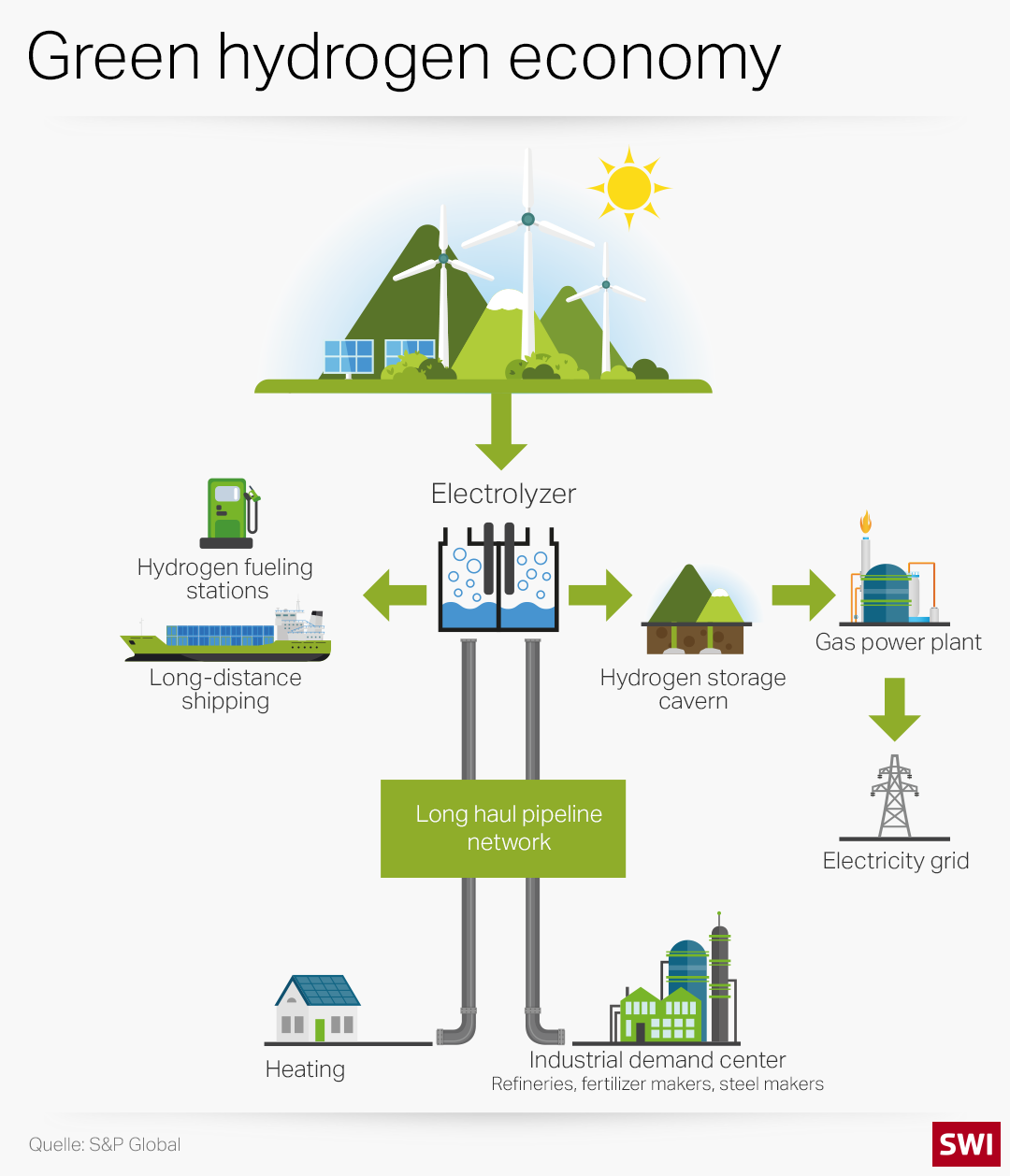

As world leaders come under growing pressure to tackle climate change, green hydrogen is gaining traction as an important part of the solution.

The potential of this carbon neutral energy source to meet up to 25 percent of global power demand will make it a key topic of debate at the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, widely seen as a last-ditch effort to put the brakes on global warming.

“Two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions come from the use of fossil fuels so that has to just stop pretty quickly and to a large extent be phased out in a number of applications,” says Jonas Moberg, CEO of the Geneva-based Green Hydrogen Organization (GH2), which launched in September with a mission to accelerate global uptake of this clean fuel. “Batteries will do a lot of it but beyond batteries you will need green hydrogen.”

Less than 1% of global energy demand is met by green hydrogen today. But the global energy landscape is shifting rapidly, with nations across the world under pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move away from fossil fuels. Switzerland is at the vanguard of countries exploring and championing clean energy solutions that don’t pollute the air or water – even though its population recently voted against a CO2 tax law aimed at steering the nation towards a greener future.

Proponents of green hydrogen point to the fact that is cleaner than fossil fuels and it can be used to store surplus wind and solar energy. The potential of green hydrogen to be an alternative to oil and gas across a wide range of applications has captured the attention of governments, clean-energy advocacy groups, and companies around the world. Australia and France plan to roll out major hydrogen power plants by 2030. Switzerland is pioneering its use in the mobility sector.

+ Switzerland’s driving role in the green hydrogen revolution

Green hydrogen is appealing because it can be produced in a climate neutral manner, Moberg says. It could be used decarbonize sectors that have hitherto been difficult to wean off polluting fuel such as industries like cement and steel, heavy-duty transport, and chemicals which together are responsible for over one third of global CO2 emissions. Green hydrogen has already shown promise as a fuel source in road transport and shipping. And it can be used for the long-term storage of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar to supply electricity.

- a fuel at refueling stations for fuel-cell electric vehicles

- in refineries to extract sulfur from fossil fuels

- an industrial gas in the steel and semi-conductor industry

- transformed into electricity and methane to power homes

- to produce green chemicals such as methanol and ammonia

CriticsExternal link, however, question the economics and climate-change benefits of using one kind of renewable energy form to create another. They say that it is more efficient to use electricity generated from renewable sources directly wherever possible. A crucial problem is that hydrogen is significantly harder to store than fossil fuels.

Green, grey or blue?

Hydrogen is a colorless gas and the most abundant element in the universe. It is normally found in compounds such as water (H20). Like electricity, hydrogen is an energy carrier, allowing the transport of energy in a useable form. It can be produced through separation from the other molecules where it occurs using sources including water (electrolysis), fossil fuels and biomass. It can be stored, liquified and transported via pipelines, trucks or ships.

How hydrogen is produced determines its environmental credentials. This has given rise to an informal color code system used to class different types of hydrogen in the energy industry. The main varieties are grey, blue and green, although these are loosely defined labels.

More than 90% of the hydrogen produced in the world comes from fossil resources such as oil, natural gas and coal. This is referred to as grey hydrogen, as production involves emissions that are harmful to the climate.

Blue hydrogen is also derived from natural gas, but the CO2 produced during the process is captured and stored permanently.

As for green hydrogen, this is produced from renewable energies. Only in this form can hydrogen play a central role in the energy transition.

Grey and blue hydrogen are considered polluting because they are produced from coal, natural gas or oil which creates carbon emissions. Hydrogen is considered green because it is carbon neutral – produced using electricity derived from renewable sources such as wind and solar. Some argue that hydrogen produced from a nuclear-powered process of electrolysis can also be green because very little carbon is emitted.

A key priority for GH2 and other renewable energy proponents is ensuring that when governments formulate their energy policies, green hydrogen takes precedence over other forms of fossil fuel and fossil-fuel derived hydrogens. It is suspicious of efforts by the oil and gas industry to promote grey hydrogen, which is sometimes “disguised” as blue hydrogen.

“The development of standards and definitions is really important – what we actually mean by green hydrogen,” says Moberg. “How do you make sure that transportation is green? That the highest green standards have been adhered to during the whole process? That’s one area that we hope to make rapid progress. It is important to make sure that those standards and definitions don’t provide ways for fossil fuel-based hydrogen to outcompete zero-emission solutions.”

Although GH2 was founded by Australian mining billionaire Andrew Forrest and is chaired by Malcolm Turnbull, a former prime minister of the country, Moberg says Switzerland was an obvious base for the organisation to drive the case for green hydrogen given the presence of so many high-profile, influential international organizations and industry players. GH2 wants get the topic on the agenda of the World Economic Forum, which will be held again in Davos, as well as at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Switzerland embraces hydrogen

The International Energy Agency estimates that global energy demand will increase by up to 30% by 2040, which will only exacerbate climate change if coal and oil dependent economies fail to embrace clean and renewable energy sources. Many experts believe green hydrogen needs to be part of the energy mix to ensure the earth’s temperature doesn’t rise beyond the 1.5°C target set in the 2015 Paris Agreement, a global covenant to mitigate climate change.

“Hydrogen is the key component in storing renewable energy,” says Andreas Züttel, president of the Swiss Hydrogen Association, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. “We can produce hydrogen and then use the hydrogen either directly or to produce synthetic fuels with CO2 from the atmosphere. That’s the reason why there is so much excitement about hydrogen. No matter what you do, we will need hydrogen.”

Not only will green hydrogen improve the flexibility of power-supply systems by providing seasonal storage for wind and solar, it also has key advantages over batteries and ammonia, Züttel says. Hydrogen as an energy carrier is produced from abundant water and has a high energy density, so fewer resources are consumed to store the energy it produces compared with batteries, he notes. Hydrogen as a fuel can also be stored safely, unlike ammonia, which is highly toxic and difficult to handle.

The European Green Deal – the European Union’s roadmap to implement the Paris Agreement commitment to become carbon neutral by 2050 – recognised the game-changing potential of hydrogen as a key energy carrier. It is also part of Switzerland’s energy strategy, and although the Alpine nation has no chance of emerging as a global leader in green hydrogen production, it is a key innovation hub.

Switzerland is pushing to establish a green hydrogen ecosystem in its mobility sector to meet the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. As part of that strategy there are plans for some 1,600 hydrogen-powered heavy-duty Hyundai trucks to be on Swiss roads by 2025, and based on an annual mileage of 80,000km a year, that would lead to an annual cut in CO2 emissions of 70 to 75 metric tons per truck, according to the South Korean company.

The Swiss Hydrogen Association brings together companies and scientists focused on developing know-how in the industry. It includes a constellation of start-ups and firms like Aquon, which developed the first solar and green hydrogen-powered motor catamaran, as well as experts from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL). Switzerland-based multinationals including the global container Mediterranean Shipping Company and commodity trader Trafigura are also investing in green hydrogen solutions and exploring its viability as a maritime fuel.

Challenges to overcome

Despite the growing wave of support for green hydrogen, there are many challenges to overcome. Mass production of the energy source is still not economical or technologically possible.

The technology to produce hydrogen on a large scale remains in its infancy, says Züttel. Progress has been made – until five years ago an electrolyser could not generate more than 4 megawatts (MW) of power, although today that’s increased to 5 MW and there are plants in operation that can generate up to 20 MW when electrolysers are put together. Alpiq, EW Höfe and SOCAR Energy Switzerland are planning to build an electrolysis plant with a capacity of up to 10 MW in the central canton of Schwyz. But that still lags far behind the capacity of a thermal power station which can be 1,000 MW or more.

The other challenge is cost. Hydrogen is currently two to five times more expensive to per energy unit to produce than fossil fuels, notes Züttel. In Switzerland, 1 gigawatt would cost approximately CHF1.5 billion to produce and take up the same space as 50 buildings of more than 200 square metres each.

The International Energy AgencyExternal link estimates less than 0.1% of global dedicated hydrogen production is currently green hydrogen, but Moberg is confident that it can be scaled up to meet 25% of the world’s energy needs by 2050. That will require government, industry leaders and international organisations to work together to build global markets and infrastructure, he says.

Bloomberg New Energy FinanceExternal link estimates that for hydrogen to account for 24% of the world’s total energy needs by 2050, some $11 trillion of investment would be required for the necessary production, storage and transport infrastructure. On top of that, governments would need to provide some $150 billion in subsidies up until 2030 and provide more policy support to boost demand for green hydrogen and drive down the cost of production to make it competitive, it said in a report in March 2020.

Producing hydrogen corresponding to 25% of Switzerland’s energy demand using photovoltaics [solar energy], would require an investment in the order of CHF100 billion, according to Züttel. Just building the pipes to transport hydrogen from power stations to the homes, offices and factories that will use it represents a long-term and large-scale endeavor akin to creating a nationwide power grid or electrifying the railway system, he adds.

“That’s completely out of the current economic behavior” says Züttel. “Today we want to invest and get a return in a few years, not in 50 to 70 years. It takes time until a sustainable energy system pays off and the people realize the advantage of a new technology. Future generations are going to appreciate today’s efforts.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=cb688ed5)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.