Catholic Church issues mea culpa on apartheid

The Catholic Church in Switzerland dealt with apartheid “hesitantly” and allowed itself to be influenced by business interests, a church-commissioned study has found.

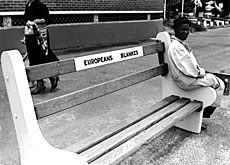

Historians looked into the church’s approach to South Africa’s racial segregation regime between 1970 and 1990 and found “a cautious and rather hesitant approach towards the issue of apartheid” prevailed.

Church leadership often reacted defensively and with foot-dragging to demands to tackle apartheid more robustly, according to the report commissioned by the National Justice and Peace Commission of the Swiss Bishops Conference.

“The position of the church leadership reflected the circumstances in Swiss society at the time,” historian Bruno Soliva, co-author of the study told swissinfo.ch.

“The Catholic Church was firmly rooted in the conservative milieu; the church leadership in particular was linked to the middle classes and took up their interests, partly subconsciously,” Soliva said.

From 1980 there was a new tendency in the Catholic Church towards more conservatism, “also through the Polish Pope John Paul II”, Soliva said. “This strengthened the position of those circles that feared a communist revolution in South Africa.”

At the presentation of the report in September, Abbot Martin Werlen, speaking on behalf of the Bishops Conference, said that from today’s viewpoint it was regrettable that the Swiss church leadership did not act more forcefully and courageously against apartheid.

The Swiss Catholic Church was also influenced by its counterpart in South Africa which never took a clear position on the use of sanctions as an instrument against the apartheid system.

Christian caution

The centre-right Christian Democrats, which rejected a boycott against South Africa, also played a braking role on the issue of apartheid. It is difficult to establish whether the party had an influence over the church leadership, according to Soliva. There are fewer written sources on this matter than oral witness statements.

“There were meetings between the church and the Christian Democrats but the issue of South Africa was seldom discussed. The political centre in Switzerland did not really concern itself with apartheid. It was an issue with the Social Democrats, on one side pushing for sanctions, and the Radicals and the Swiss People’s Party on the other side against sanctions.

“Christian Democrat parliamentarians were often on the boards of large or medium-sized banks. There were also Christian Democrat politicians in bank management, “although this was mainly the preserve of Radicals”.

Business as usual

Bishops were little interested in economic issues but influenced by business representatives or state officials in the service of the economy. “Business figures were especially effective when they warned of a communist revolution in South Africa.”

But the banks and business lobbies probably had a greater influence on the Protestant Church than on the Catholic Church.

“That is because in those days businessmen and bankers were more likely to be Protestant. The Catholic Church had to reject neo-liberalism on the grounds of their social teaching,” said Soliva.

“There was, however, in both churches a certain level of distrust towards business circles. But they didn’t want ruin things completely with them.”

The churches as a whole were less under pressure from business people and rightwing conservative circles than the Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund and the Protestant charity Bread for All (Bread for Brothers at the time), according to the historian.

Reds under the beds

The issue of apartheid in South Africa was discussed in an international anti-communism context.

“At the same time there was also an older ‘philosophical’ anti-communism that persisted in the Catholic Church. And the church leadership distrusted the Liberation theology that had emerged from South America, suspecting that it was infiltrated by socialism.”

The church also bowed to the criticism of rightwing conservative groups.

“They reacted in a contradictory way: They always took the position that human rights must be defended. But when it came to bravely going public and for example also supporting economic sanctions against the apartheid regime, they were afraid of conflict,” Soliva said.

Grass roots

The Catholic Church leadership was overburdened, the historian says.

“They wanted to avoid these conflicts and often simply do nothing or too little. A decisive part of this was that apartheid was an important issue in church circles at that time; there were grass-roots church groups like Student Christian Youth as well as the Cairo working group of the Theological Movement for Solidarity and Liberation.”

“A bit more engagement and decisiveness on the part of the Swiss Catholic Church in its commitment to human dignity and the rights of all people in South Africa would, in hindsight, have boosted the credibility of the church leadership,” Soliva said.

“The Church leadership would have done better to have taken more notice of the voices of the engaged grass roots and the experienced members of mission societies earlier and to have done so earlier;” the study concludes.

“Human rights issues transcend the stereotypical left-right divide and the considerations of the time run the risk of being overtaken by history.”

1950 – The South African parliament votes in four laws establishing apartheid. At that time, Ciba (now Novartis), Roche, BBC (now ABB), UBS’s predecessor bank, and other large Swiss firms create subsidiaries in South Africa.

1956 – Swiss South African Association is created to serve like a chamber of commerce.

1960 – March 21, police kill 69 black demonstrators. A general strike and brutal repression ensue. The ANC is banned.

1963 – The UN calls for an embargo on arms sales to South Africa. Switzerland imposes a ban on exports.

1964 – Mandela and other ANC leaders are sentenced to life imprisonment.

1968 – Switzerland condemns apartheid at UN Conference on Human Rights. Swiss banks create a purchasing pool for gold and Bern asks the Central Bank of South Africa to erase Switzerland from its statistics. By the late 1980s, Switzerland has bought SFr300 billion worth of gold from South Africa.

1974 – Bern caps Swiss investment in South Africa at SFr250 million a year (and SFr300 million from 1980). The limits are easily circumvented.

1976 – Soweto uprising sparks confrontation which leads to nearly 600 deaths.

1986 – Switzerland begins to support South African NGOs that defend human rights and democratisation, spending SFr45 million by 1994.

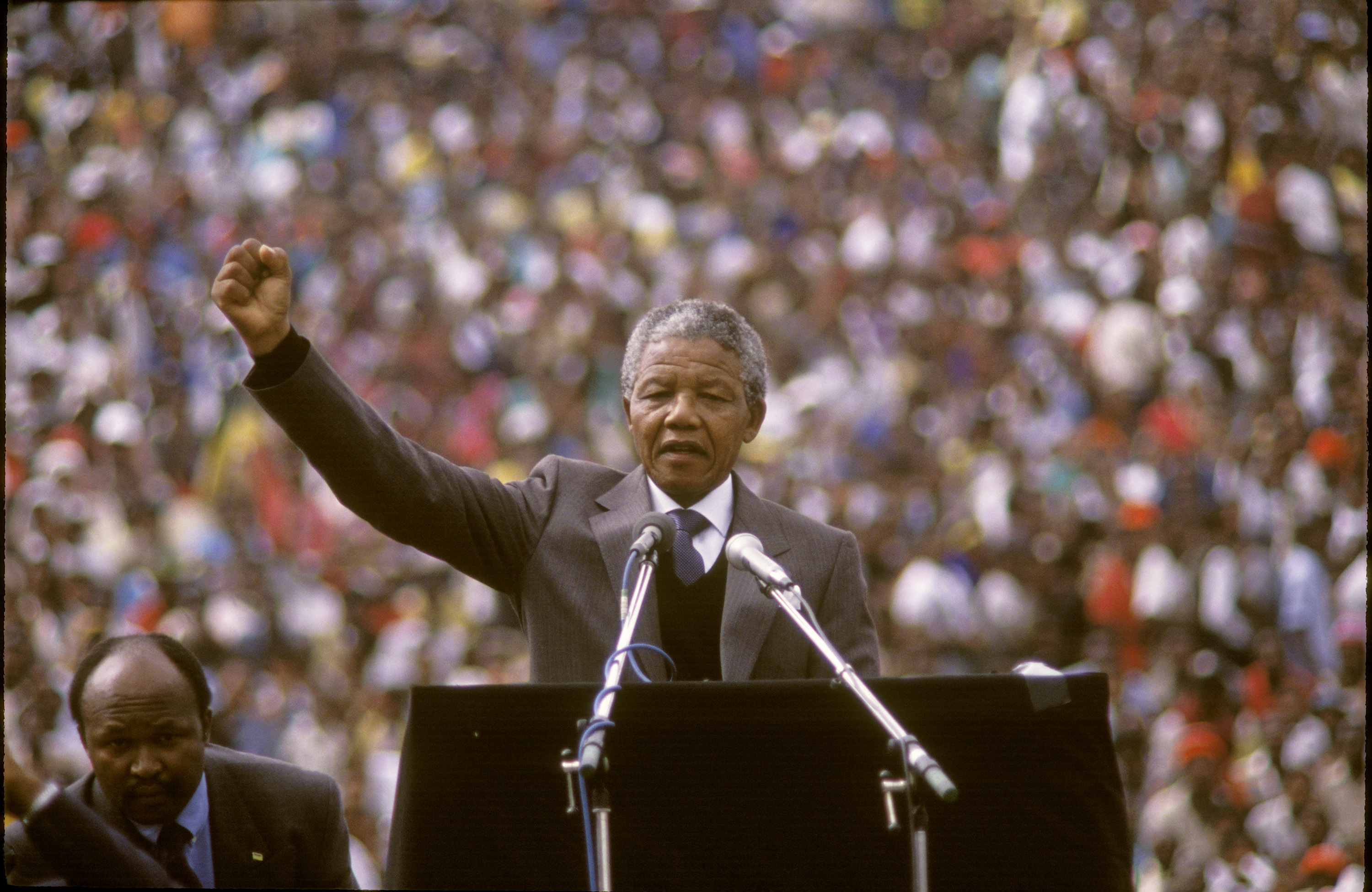

1990 – ANC ban lifted. Mandela is released on February 11. On June 8, he arrives in Switzerland and meets Foreign Minister René Felber.

1994 – April 27, the first general elections in South Africa. Landslide victory for the ANC. Mandela becomes the first black president of the country.

“The Catholic Church in Switzerland and its approach to Apartheid in South Africa (1970 to 1990)”, published in September, was commissioned by the Swiss National Justice and Peace Commission of the Swiss Bishops Conference and written by historians Bruno Soliva and Stephan Tschirren.

The Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches commissioned similar studies some years ago and afterwards openly regretted that it had applied itself too long to negotiations and not enough to taking a position.

That the Catholic Church is only getting around to the task now, Burno Soliva attributes “in part to circumstances or personnel combinations at the Bishops Conference or Justice and Peace that delayed work on the issue”.

(Adapted from German by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.