Emile Gilliéron, the Swiss iconographer of the first Olympic Games

Swiss artist Emile Gilliéron designed the poster, trophies and commemorative stamps for the 1896 Olympics in Athens. An exhibition at the Louvre in Paris is paying tribute to his work.

The commemorative-album cover for the first modern Olympic Games – held in Athens in 1896 – has long been considered the first Olympic poster. It features a Greek woman holding an olive wreath and myrtle branches, the winners’ prizes. Until recently, no one knew who had created it. But in 2018, research by the École française d’Athènes (French school of Athens) finally revealed the designer: Emile Gilliéron, an accomplished Swiss artist.

By the 1890s, Gilliéron was an expert on antiquity, and his poster offers a subtle mix of ancient images. Hercules appears in the foreground as a child, symbolising Olympia, birthplace of the Olympics. The Acropolis in Athens is visible in the background. Baby athletes decorate the very top, copied from a sarcophagus from … ancient Rome!

Gilliéron was not only an illustrator, draughtsman, sculptor and populariser; he was also an aesthete and, in his own way, an inventor. The first Olympic Games gave him a dream opportunity to practise his skills on a grand scale.

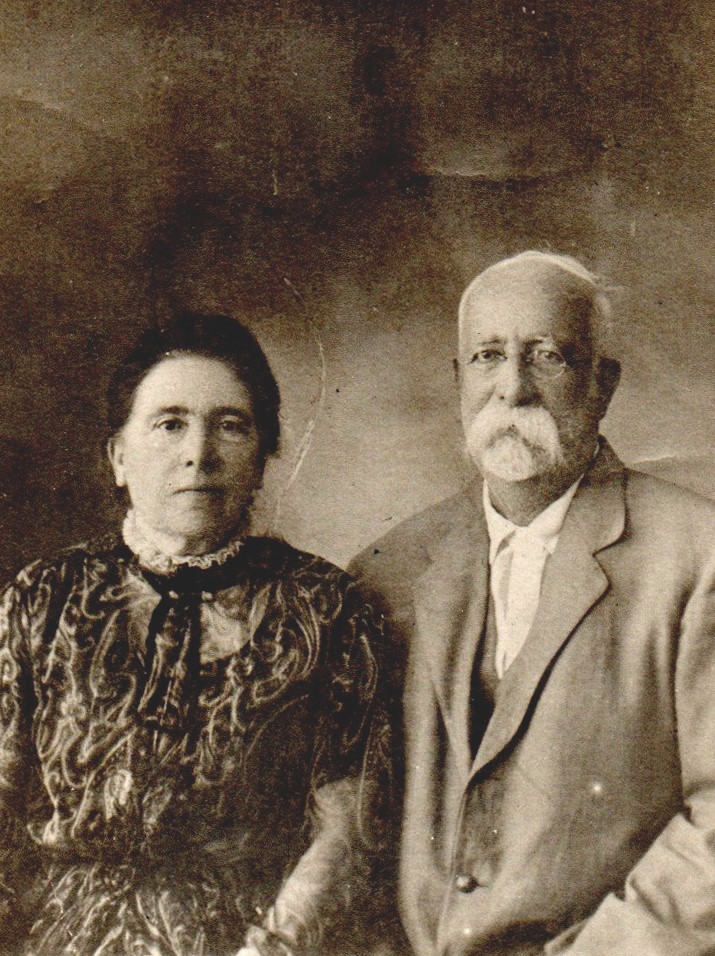

Born in Villeneuve in canton Vaud in 1850, he attended secondary school in Neuveville in the Jura mountains of canton Bern. He went on to study art in Basel, Munich and Paris, where he sharpened his talent in front of the Greek antiquities at the Louvre. After arriving in Athens in 1876, he taught painting to the children of King George I of Greece.

The young Greek state at the time was alive with nationalist and archaeological fervour. Excavations everywhere were resurrecting the glories of the ancient past. Gilliéron worked on digs at the Acropolis and at Mount Athos and honed his new craft: reproducer of ancient art. He became famous for his bas-relief watercolours, which he sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and other major museums.

Football or discus throw?

At the same time, in Paris, ideas of modern OlympismExternal link were taking shape. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, secretary general of the fledgling International Olympic Committee, dreamed of establishing new Games – and Greece seemed the ideal location because of its Olympic tradition and its aura of Athenian democracy. De Coubertin wanted, however, to feature bicycle competitions, hot-air balloon races, football and the like instead of ancient sports.

A friend of de Coubertin’s, linguist Michel Bréal, had a more romantic vision. In September 1894, Bréal wrote to de Coubertin: “Since you’re going to Athens, why don’t you see whether we can organise a race from Marathon to Pnyx. That would emphasise the character of Antiquity,” he wrote. In 490BC Greek messenger Pheidippides is said to have run from the city of Marathon to Athens – about 42 kilometres – to announce victory against the Persians.

“If we knew how long the Greek warrior took, we could set the record. For my part, I’d claim the honour of presenting the ‘Marathon cup’.” Bréal, at 62, had never been to Greece and was not much of a runner, but he had just invented the marathon.

Cups, vases and stamps

The new Games would require cups, trophies and medals. Emile Gilliéron gave free rein to his talent for reproductions but also to his overflowing imagination. He produced cups, vases, goblets and stamps to commemorate the event. “The 1896 stamp edition helped finance the Games. These were the only stamps available in Greece at the time,” explained Alexandre Farnoux, one of the curators of the show at the Louvre.

The Greeks, only partially persuaded by the idea of modern sports, felt the new Games should include traditional Olympic disciplines. But some of the required skills were unfamiliar to them. What, for example, was the correct way to throw a discus? A famous 5th-century sculpture of a discus thrower – Myron’s Discobolus – offered them clues about throwing technique. Chronophotography, a forerunner of film, helped deconstruct the motion. An American nonetheless ended up winning the discus in 1896, with Greeks placing second and third. This didn’t stop Gilliéron’s Discobolus stamp from becoming one of his bestselling.

Excellent businessman

By the 1890s, the Swiss artist was well established in Athens and owned a magnificent house across from the ancient church of St. Dionysius. “He enjoyed a triple career, soon aided by his son,” said Christina Mitsopoulou, head of the “Projet Gilliéron” at the Ecole française d’Athènes and a curator of the Louvre exhibition.

Gilliéron ran the casting workshop at the National Archaeological Museum. He also sold, through his own company, high-quality casts and reproductions, especially internationally. And he produced ancient-style murals.

“Sometimes his various activities conflicted with each other. The Greek authorities were, for example, surprised by the spread of reproductions before the originals were even made public,” said Mitsopoulou, who added that Gilliéron was a “very good businessman”. He resumed his Olympic work with similar success for the 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens.

Gilliéron occasionally freed himself from archaeological truth in favour of artistic creativity. While this posed no problem for the Olympic Games, which liberally reinvented Greece’s image, it was more troublesome in other situations. During excavations led by the British archaeologist Arthur Evans at Knossos in Crete in 1905, Gilliéron and his son “reproduced” a Prince of the Lilies fresco that owed more to their imaginations – or to Evans’s wishes – than to reality. Mitsopoulou explained that “the distinctions we now draw between faithful reproductions, imitations and interpretations were less sharply defined at the time”.

Although Gilliéron was highly regarded in his day, at least among lovers of Greece, his fame faded over time. “The great archaeologists like Arthur Evans or the German Heinrich Schliemann rarely named their colleagues, and this bothered Gilliéron, who was very aware of his skill,” Mitsopoulou said.

But the rediscovery of his work is gaining speed. After the show at the Louvre, Mitsopoulou intends to organise an exhibition in Gilliéron’s native Switzerland to mark the 100th anniversary of his death in 1924.

Olympism: Modern Invention, Ancient Legacy – at the LouvreExternal link museum in Paris until September 16, 2024.

Adapted from French by K. Bidwell/ts

More

Newsletters

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.