Swiss synagogues reflect the way to acceptance

Once a tiny, marginalised group, targets of discrimination, the Jews of Switzerland are today citizens like anyone else – and it would be shocking if they were not.

The changing architecture of synagogues over the past 160 years or so reflects the route followed by Swiss Jews as they sought their place in Swiss society.

Architect Ron Epstein, himself a member of the Conservative Jewish community, has written a richly documented book about Swiss synagogues, Die Synagogen der Schweiz (The Synagogues of Switzerland), in which he explains how the Jewish community saw its religious buildings as demonstrating its newly acquired equality and as an expression of its Swiss identity.

“As an architect, what I find interesting is acculturation, the adoption of bourgeois cultural values,” he told swissinfo.ch.

Both the Jewish and non-Jewish press would report on the opening of new synagogues, he says in his book. The Jews were portrayed as eager to integrate, with their synagogues an assertion of the equality of their religious community.

Foreigners – and foreigners

Until three-quarters of the way through the 19th century Swiss Jews were literally foreigners in their own country.

Treated as outsiders, denied citizenship, they were next to invisible to the majority Christian population. Already discriminated against through special laws and taxes, in 1776 a new law restricted the estimated 550-strong Jewish community to the two villages of Lengnau and Endingen in what is now canton Aargau.

The 19th century, with its radical political and economic changes in both Switzerland and Europe, was a turning point in the fortunes of western European Jewry.

France and Germany moved much faster than Switzerland in emancipating their Jewish populations, and ironically, for much of the 19th century foreign Jews had more rights in Switzerland than Swiss ones.

Today the two Aargau villages boast the oldest of the 22 synagogues still in existence. They date back to 1847 and 1852 respectively. But although separated by only five years, the differences in architecture already reflect changing attitudes.

“In Lengnau the people wanted to integrate rather than to stand out, but the synagogue in Endingen, which opened a few years later, has some ‘orientalising’ features,” Epstein explained.

The “orientalising” features were taken over from the German and French synagogue tradition, since Switzerland had no synagogue-building tradition of its own. They were supposed to hark back to the architecture of Moorish Spain. They are certainly a far cry from Switzerland’s Christian churches.

While the Jews of Lengnau and Endingen were not granted full freedom of movement until 1879, economic pressures at home had already caused an influx of Jews from neighbouring countries who established small communities in various Swiss towns.

These communities requested plots and commissioned (Christian) architects to build synagogues. These buildings helped the Jews to assert their presence as a community.

Orientalism

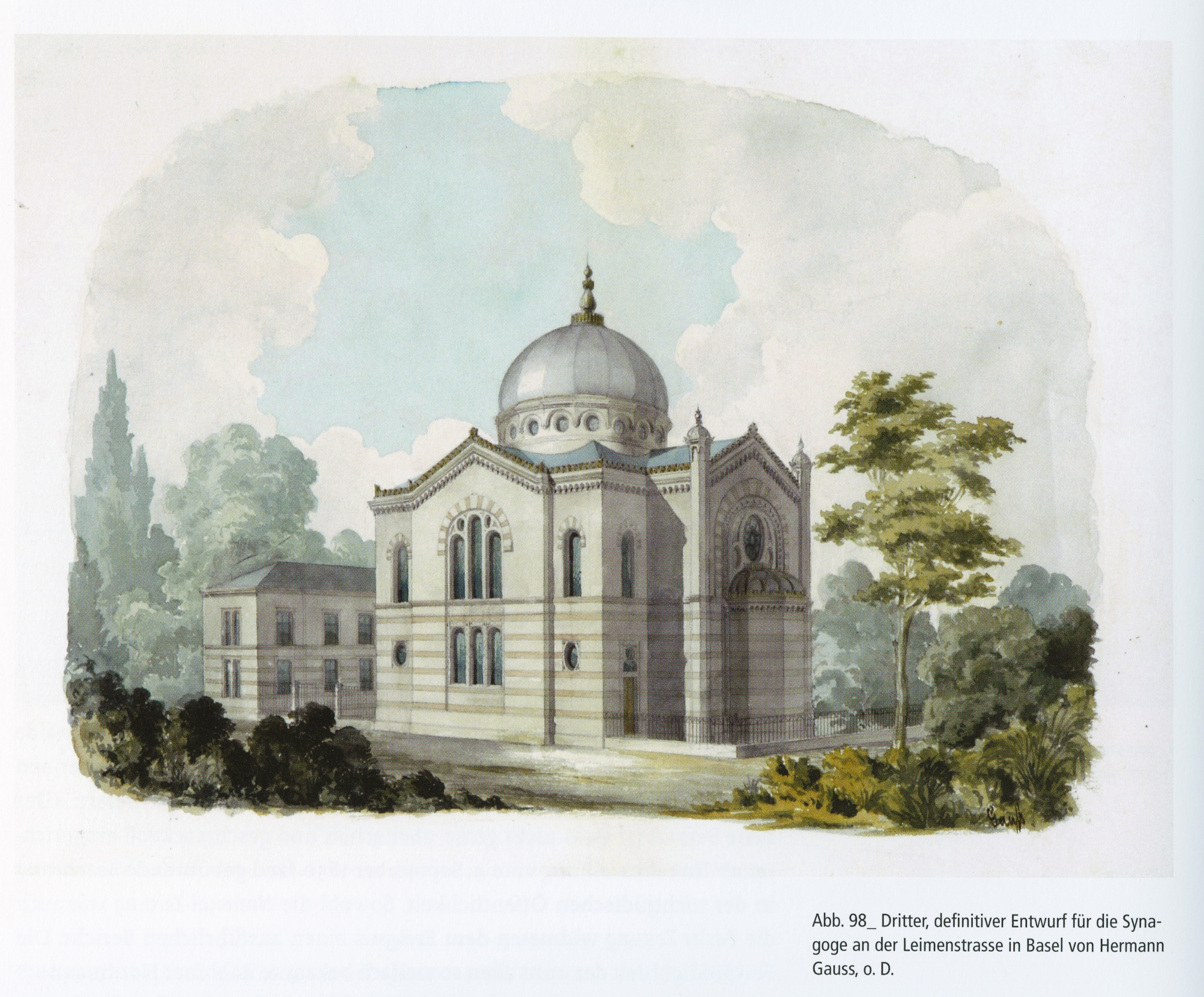

The imposing synagogues in Geneva, St Gallen, Basel and La Chaux-de-Fonds – built in 1859, 1868, 1881 and 1896 respectively – could at first sight be taken for mosques with their domes and horseshoe arches.

“It was the expressed desire of the community to assert itself in the Christian environment through prestige buildings,” Epstein writes in his book.

Zurich’s main synagogue – still in use today – was designed to show visitors to the 1882 national exhibition the contribution that the city’s new Jewish community could make to the town.

But a few decades later things had changed.

“When the Jewish population had achieved legal equality and economic integration, the synagogue stopped having a prestige value,” Epstein writes. Most later synagogues were for the benefit of the Jewish community alone.

The inflow of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe with different traditions in the 20th century is also reflected in synagogue design.

“The Orthodox didn’t really want to assimilate. Their synagogues are not huge, impressive buildings but tend to be introverted, and more modest,” Epstein explained.

Struggle for recognition

In the current controversy about the construction of minarets, is there a parallel between the Jewish experience a hundred years ago and the Muslim experience today?

“A minaret is a symbol for a building. When you see a minaret, you know straight away that is a mosque,” Epstein said.

“There is in fact also a symbol, though a much smaller one, in the overwhelming majority of synagogues, namely the tablets of the law set on the roof. But a minaret is much more obvious.”

It is not the design of the buildings where he sees parallels, but in the historical experience.

“The similarity lies in the sense that people want to document their existence as a religious community to the outside world, and this is not allowed. The struggle to achieve this is very similar to what the Jews faced.”

“What is deplorable is that nearly 200 years later this right cannot be taken for granted.”

Julia Slater, swissinfo.ch

In the Middle Ages Swiss Jews were often persecuted, as they were elsewhere in western Europe.

Later, they were subject to special taxes and laws which restricted their movements and activities.

In 1776 they were permitted to live in only two villages in canton Aargau: Lengnau and Endingen. At that time the Jewish population was about 550.

After the French invasion of 1798 and the total reorganisation of the system of government, most of the restrictions were lifted. But many were re-imposed in 1809.

In the first half of the 19th century Jewish communities were founded in several Swiss towns, by Jews who had immigrated from neighbouring countries. They enjoyed greater rights that the Jews of Aargau.

Foreign governments whose Jewish nationals had settled in Switzerland, stepped up pressure for Jews to be treated equally.

Restrictions on Jews were gradually lifted; in 1879 the Jews of Aargau finally achieved total equality with all other Swiss citizens.

Once allowed to live where they pleased and choose their profession freely, the Jews moved into the towns and cities.

In 1880 there were 7,373 Jews in Switzerland, 0.3% of the population. Many had settled from neighbouring countries.

A wave of Jews fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe started arriving in the early 20th century, changing the nature of Swiss Jewry.

During the Nazi period in Germany, Switzerland turned back many would-be refugees; however 23,000 Jews did find refuge in the country.

The 2000 census put the number of Jews in Switzerland at 17,900 (not counting those who may have described themselves as having no religious affiliation.) This is equivalent to 0.2% of the population

(in German)

Author: Ron Epstein-Mil

Publisher: Chronos Verlag, 2008

ISBN: 978-3-0340-0900-3

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.