Switzerland’s first women’s ski champion

Rösli Streiff won both the slalom and combined titles at the second Alpine World Ski Championships in Cortina d’Ampezzo in 1932. A look back at the life of the trailblazing skier from Glarus and the early days of women’s downhill skiing.

SWI swissinfo.ch regularly publishes articles on historical topics curated directly from the Swiss National Museum’s blog pageExternal link (available in German and often French and English).

Rösli Streiff was born on January 16, 1901 into a family of factory owners from Glarus. The Streiff family were sports enthusiasts: her father was a member of the Glarus Ski Club – the first in Switzerland – which was established in 1893, while Streiff and her three siblings did sports, from riding to climbing and skiing. Streiff’s first experience on skis was at the tender age of five on a pair her father had made especially. After leaving school, she attended evening classes in business, spent time in French-speaking Switzerland and in England, and started working at her parents’ bleachery in Glarus. Ernst Gertsch, who later founded the Lauberhorn ski races in Wengen, was working as a tennis instructor in Glarus in the late 1920s. After taking part in a ski tour with Streiff, he invited her to take part in the summer ski race on the Jungfraujoch, where she completed her first alpine ski race in 1928.

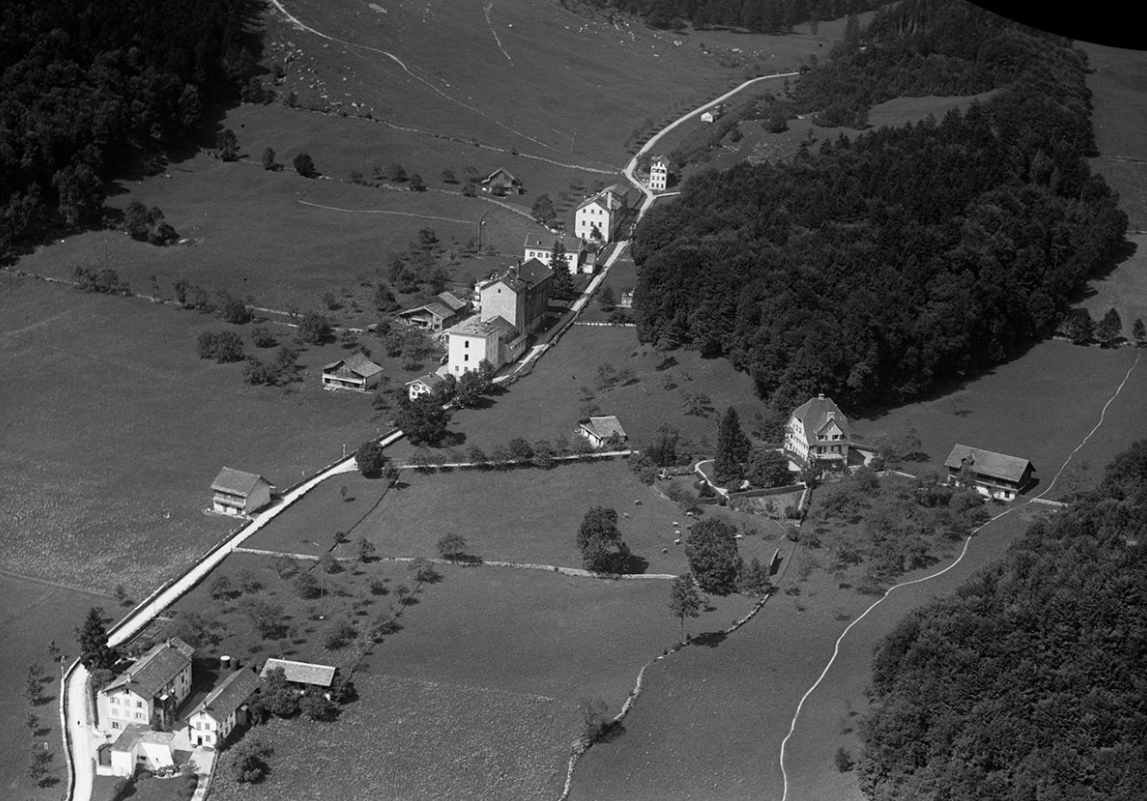

Following her initial forays into competitive skiing, she joined the Swiss Women’s Ski Club (SDS), which was founded in Mürren in early 1929. The SDS association was set up with the aim of pooling the organisation of Swiss women skiers and ensuring better training, both at competitive and amateur level. Shortly afterwards, the SDS organised its first races, offered ski lessons – initially for the top racers and later for skiers of different levels – and persuaded the Swiss Ski Association (SSV, now Swiss Ski) to allow women skiers to take part in the downhill and slalom events at the national championships in the early 1930s.

This rapid institutional progress and the dedication and commitment of female skiers partly explains the surprisingly early acceptance of women in the developing world of alpine skiing in the 1920s and 1930s, compared with Nordic ski disciplines and other sports, such as football. In addition, the female pioneers and early SDS members were very well connected, lived in the emerging tourist resorts such as Mürren, or came from families who owned chalets there. They skied with local spa managers and enjoyed a privileged social status, as was the case for Rösli Streiff.

Like all downhill skiers, however, she was an amateur, which meant she spent most of her time in the office at her parents’ bleachery rather than on the slopes. Meanwhile, the best male skiers were often ski instructors. Within the SSV association, some top figures were concerned that the dominance of Swiss men in international competitions would be tarnished by the women. This limited its willingness to promote women in skiing – a gap that was filled in part by the SDS.

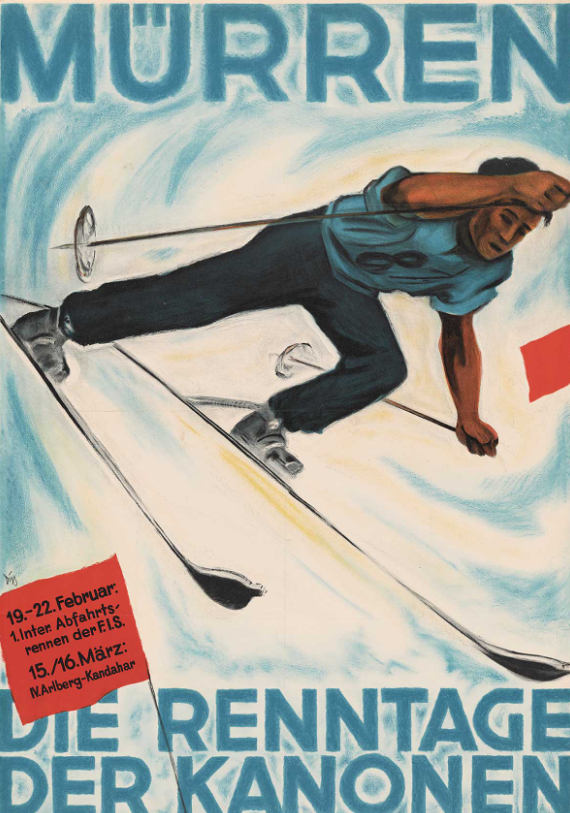

The International Ski Federation (FIS) officially accepted the alpine disciplines of downhill and slalom for international competitions at its congress in Oslo in 1930. The following year, the first alpine World Championships for both men and women took place in Mürren in the Bernese Oberland from February 19-22. While the SSV put together the men’s national team, for the women’s team this task was left to the SDS. Rösli Streiff was part of the seven-strong squad, which also included Ella Maillart and the subsequent administrative director of the SSV and FIS official, Elsa Roth. While the men clearly dominated the competition, the women skiers failed to make much of an impact of the leader board.

However, 1932 turned out to be a great deal more successful, particularly for Rösli Streiff. At the first combined downhill and slalom race organised by the SDS for women skiers from all countries, which was held in Grindelwald on January 15 of that year, she won both the downhill and the slalom, thereby taking the combined title. This competition, which from then on took place every year, was the only women-only event internationally. It evolved to become a key date in the ski calendar and played an important part in the popularisation of women’s skiing. In 1932, it was still mostly Swiss skiers taking part, however, with ten of the twelve competitors coming from Switzerland. At the major Swiss ski race held in Zermatt in late January 1932, Streiff repeated her triple victory and dominated the national competition once again. Straight after the award ceremony, she had to travel on to Brig to catch the next train for Italy.

Rösli Streiff travelled with three other women and the members of the men’s national team to Cortina d’Amprezzo, where the second World Ski Championships were held from February 4-6. In the downhill on the first day of the competition, Streiff was nowhere near the top of the leader board, finishing in eighth place.

But a convincing victory in the slalom secured her not only the slalom title, but also the combined. Years later, Streiff revealed the secret of her success. She explained that the Swiss winner of the men’s combined event in Cortina, Otto Furrer, had advised her and the other women skiers to do the slalom with stem turns in order to ski as close to the gates as possible and therefore achieve a faster time.

The SDS covered the women’s travel costs to Italy, as the national skiing association (SSV) was still reluctant to support women in alpine ski racing. The association only started offering race training for women in 1942. By then, Rösli Streiff had not been part of the national ski team for six years.

Following her career as an amateur ski racer, in 1939 Rösli Streiff signed up to the first women’s recruits school and served as a truck driver in the women’s auxiliary military service. For five years in the 1950s, after her father died, she and one of her brothers took over the management of the family’s bleachery, where she worked for 37 years in total.

Rösli Streiff continued to do sport into old age and travelled a great deal, practising downhill skiing in Mürren and water skiing in Canada. There was no media frenzy surrounding her during her skiing career. In fact, as a correspondent for the NZZ newspaper, she sometimes even reported on her own races. But from around the mid-1970s, there was renewed interest in the story of Switzerland’s first female world ski champion, and aged over 70, Streiff was suddenly in demand, with all the newspapers, radio stations and televisions channels wanting to interview her. Up until her death at the age of 96, she regularly reported on the early days of skiing, when the female racers still had to climb up to the start line. She recounted anecdotes about the top skiers and always emphasised the great camaraderie between the female competitors.

Her rediscovery in the media occurred just at a time when skiing was experiencing a boom in Switzerland, attracting a great deal of media coverage, and when feelings of nostalgia for a bygone age were playing a part in the collective memory of Switzerland as a skiing nationExternal link. The delayed recognition of Streiff’s pioneering role and her modest yet self-assured manner meant that, in the eyes of the public, she only became a skiing heroine in later life, although in fact she had been one for many years.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.