The heady history of humans and alcohol

Alcohol has been a companion to humankind since the year dot: as an enjoyable beverage and addictive substance, but also as a hygienic alternative to water and even as a remedy for intestinal worms. A short cultural history of an everyday toxic substance.

It is said that the Germanic peoples would discuss every matter twice – once when drunk and once when sober. Only if a proposal was accepted in both states would it pass. If we are to believe this account by the Roman historian Tacitus dating back to around 100 BCE, alcoholic beverages were an integral part of Germanic life. Indeed, beer and wine have been dietary staples of many cultures in the Western world for centuries.

SWI swissinfo.ch regularly publishes articles from the Swiss National Museum’s blog External linkdedicated to historical topics. The articles are always written in German and usually also in French and English.

But their history probably goes back much further. Research suggests that even our apelike ancestors had contact with alcohol. Both the taste and smell of this chemical compound activate a part of the brain that triggers a sensation of hunger. Ripe fruit contains more sugar, is therefore more energy-rich and releases volatile substances, including ethanol. It is thought our ancestors could smell this over long distances. In his book A Short History of Drunkenness, Mark Forsyth describes the theory that ten million years ago, our ancestors sought out overripe fruit in their droves. A genetic mutation that occurred at this time also resolved the problem of alcohol processing in the body.

Beer: a hygienic thirst-quencher and pick-me-up

In the Neolithic period, when humans settled and started to grow crops, various cultures began systematically producing alcoholic beverages. Archaeologists can prove this with great certainty as they have discovered residues of tartaric acid (which is contained in wine) in containers that are thousands of years old. In China, the earliest discoveries date back to around 7000 BCE, while residues found in Iran and around the Mediterranean are thought to have originated a little later. Meanwhile, many depictions on statuettes and in paintings reveal that beer and wine had already been everyday beverages and foods (yes, foods!) for thousands of years before the common era in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Babylon and Crete. The Egyptians, for example, long emphasised the nutritional value of beer because of the vitamins and trace elements it contains. Beer was also less likely to be contaminated than ordinary drinking water, which made it a welcome thirst-quencher for centuries. In the eleventh century, the Anglo-Saxon monk Ælfric wrote that he drunk “ale if I have any, and water if I have no ale.”

Besides its role as a thirst-quencher, alcohol also has a long history as a remedy for other health issues. In the 13th century, for example, Catalan physician Arnau de Villanova described how alcohol could help treat intestinal worms and prevent seasickness. Up until the 20th century, Western medicine recommended beer to certain groups. The Swedish physician Carl von Linné said in 1784 that beer was beneficial to those “who were thin, dehydrated, or involved in hard manual labour needing sustenance and energy”. Until around a century ago, alcohol was also the only painkiller and anaesthetic substance in medicine, as well as an effective antiseptic.

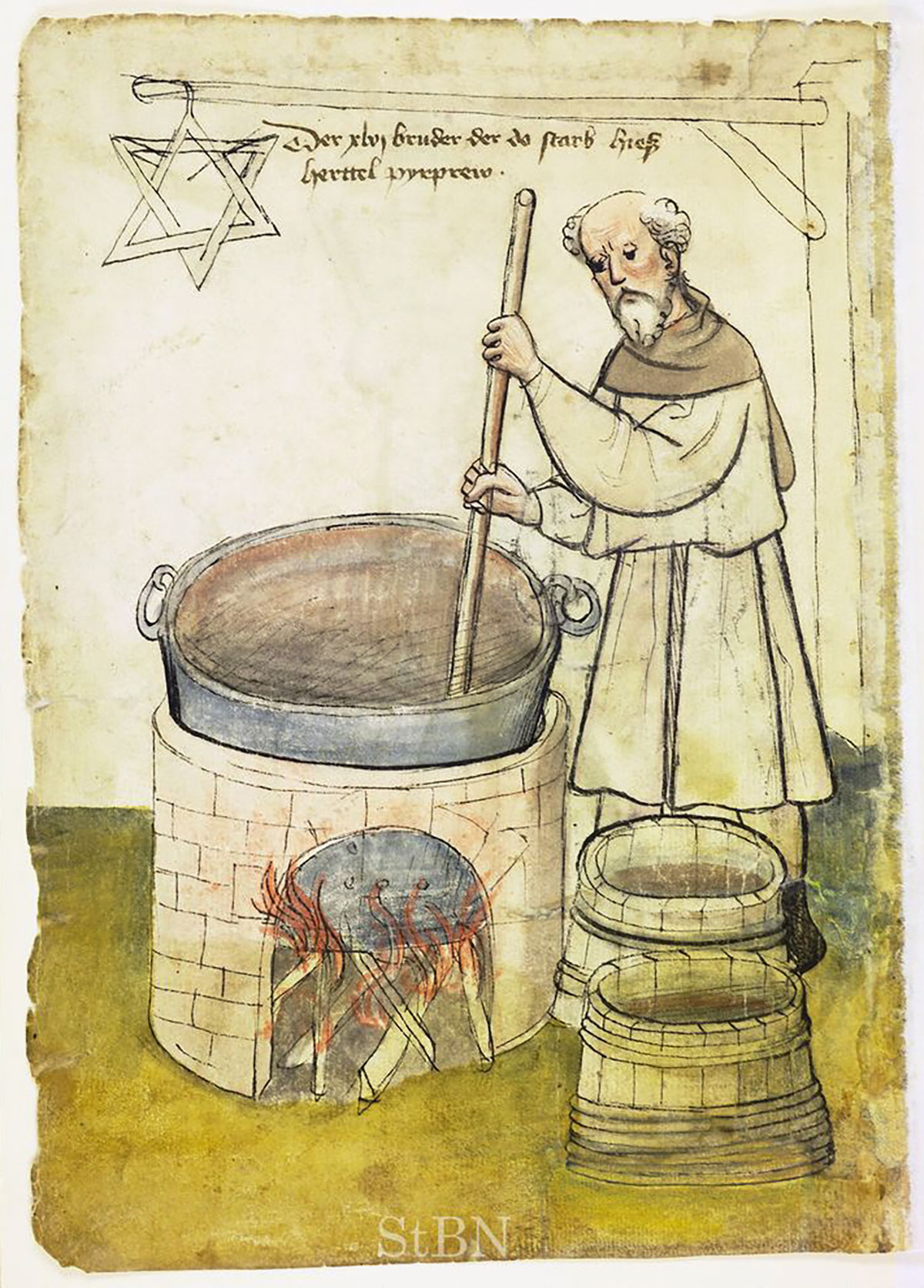

Spirits as waters of life

But it was alcohol’s intoxicating effect in particular that appealed to people. Spirits – in other words, high-proof alcoholic beverages – offered the easiest way to reach this state of intoxication. However, the production of spirits first required the invention of the distillation method, which in all likelihood came from North African Arab alchemists in the 10th century. It is difficult to pinpoint when this production method became known and used in Europe; however, from the 15th century, distilled alcohol is mentioned in books on medicine and alchemy. Over the next two centuries, distillers in western Europe industriously produced all manner of spirits – also known as aqua vitae or waters of life – from whisky and gin to brandy and others. Gin was to blame for a social crisis that occurred in early 18th century London. According to an article in the London Magazine, gin was “sold in almost every house somewhere, usually in the cellar”. It was very high proof – believed to contain up to 80% alcohol –, it was cheap, and it could be produced tax-free and without a licence. Gin was therefore particularly popular among the poor, who drunk it watered down with turpentine and sulphuric acid. The high gin consumption had disastrous consequences, and it wasn’t for nothing that it was dubbed ‘mother’s ruin’. It even led the country’s death rate to temporarily exceed the birth rate. The government tried desperately to curb consumption through various legislation, including the introduction of liquor licences. A series of failed harvests in the 1750s did the rest and the miserable phase, which would soon go down in history as the ‘Gin Epidemic’ or ‘Gin Craze’, abated.

In the area that is now Switzerland, consumption of schnapps remained moderate until the late 18th century. That changed when the potato found its way into local agriculture. The tuber was ideal for producing a spirit known as ‘Hardöpfeler’. Many peasants and artisan families who had been pushed to the verge of ruin by industrialisation, saw distilling potato spirit as a chance of survival. This also led to a rise in consumption, both among farmers and factory workers, for whom the beverage was an effective way of altering their state of mind after a long day of hard labour. Swiss historian Jakob Tanner wrote: “Inebriation was the ‘other’, it was a way of freeing oneself, of sinking and disappearing.”

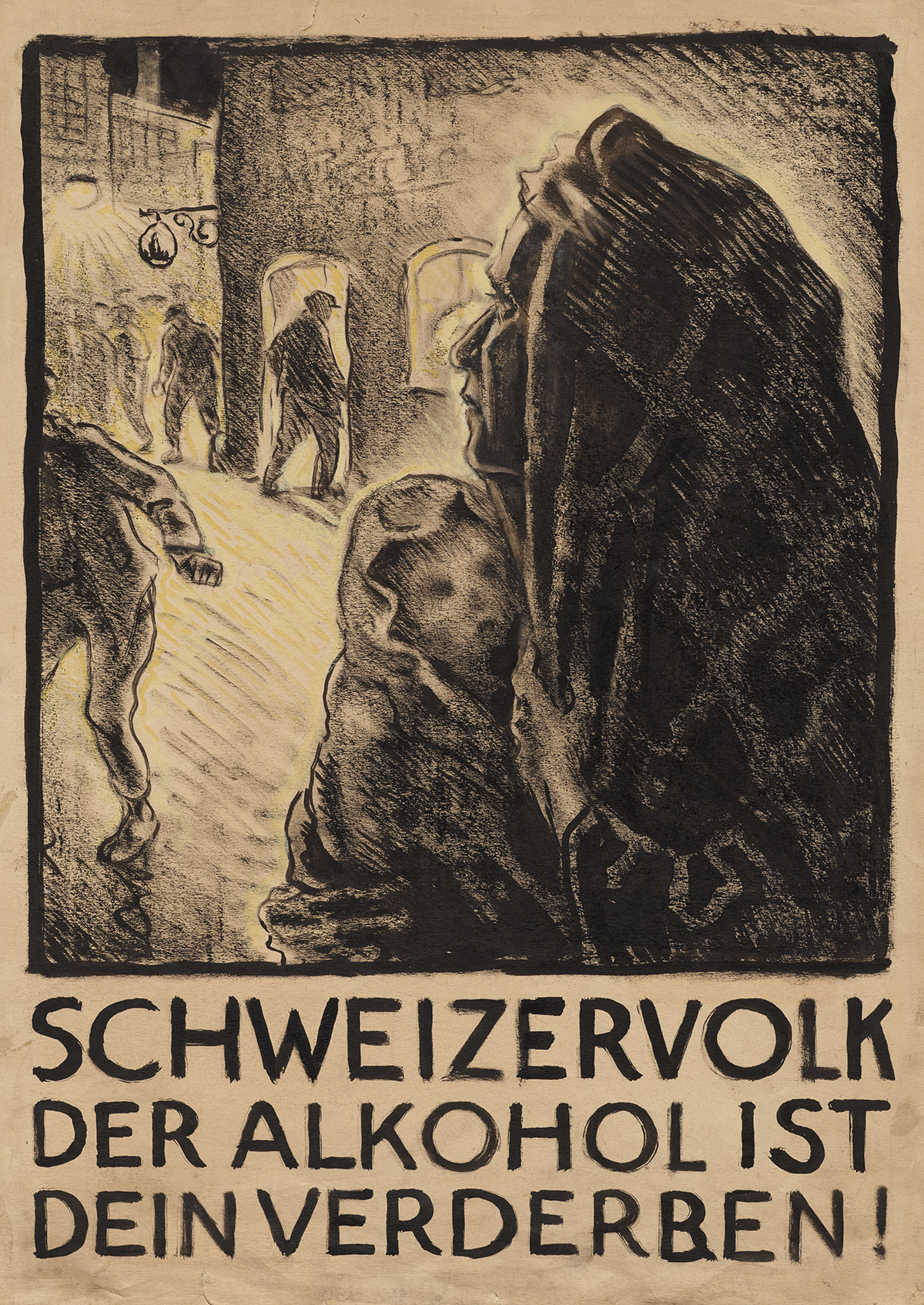

The alcohol problem

As is well known, alcohol consumption is not without its consequences. This was noted in the late 18th century by several doctors in Scotland, Germany and the US who established the terms ‘addiction’ and ‘alcoholism’ in their works, and warned against excessive drinking. In Switzerland, Genevan doctor Ernest Naville was one of the first to study alcohol addiction in 1841, citing a range of causes: the cheap availability of alcohol, a culture of permissiveness and drunkenness in the military, and precarious housing situations. Following the American example, Switzerland also saw a temperance and abstinence movement. Genevan priest Louis-Lucien Rochat set up the Blaue Kreuz in 1877 to help addicts. The Swiss federal government also recognised the need for action on the alcohol issue. In the mid-1880s, it introduced a state alcohol monopoly and an alcohol tax: measures that clearly paid off, as the age of ‘miserable alcoholism’ in Switzerland was deemed over by the 1930s – although people were still drinking as before.

According to the Addiction Switzerland foundation, some 85% of people aged 15 or over in Switzerland now regularly drink alcohol. Almost 9% drink daily and it is estimated that 250,000 are alcohol-dependent (can’t go without alcohol or would find it very difficult to do so). The World Health Organization (WHO) warned in a recent study that no level of alcohol use is safe for our health, and that the risk starts from the very first drop.

Whether as a quencher of thirst, a cure for disease, or as balm for the soul, humankind has used alcohol since time immemorial. So it’s not about to disappear anytime soon.

Isabelle Hausmann is studying history and works as an editor.

Read the original articleExternal link on the Swiss National Museum’s blog

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.