The Olympic truce: noble myth, harsh reality

The International Olympic Committee and the United Nations are hoping for a ceasefire in armed conflicts, including between Russia and Ukraine, during the Paris Summer Games. In reality, the Olympic truce is rarely respected. We take a look at the history behind this 'invented tradition'.

On his visit to Paris in May, Chinese President Xi Jinping supported the principle of an Olympic truce, proposed by the the UN and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and approved by the French president, Emmanuel Macron.

So far, Moscow has not rejected the call for a truce. It would be expected to start a week before the Olympic Games, that is, on July 19, and to end a week after the Paralympic Games, on September 15. The Kremlin, however, says that “as a general rule, the Kyiv regime uses this kind of idea or initiative as an opportunity to regroup and re-arm.”

“The Russian forces, who are currently doing well in the war against Ukraine, are following their own agenda, and probably wouldn’t favour the idea of a truce,” says Russia specialist Lukas Aubin, the head of research at IRIS, the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs. Moscow feels humiliated by the actions of the IOC, Aubin points out: Russian and Belarusian athletes are not allowed to compete under their national flags.

Will the Olympic movement succeed in getting what other international bodies have so far failed to achieve – a ceasefire, even a provisional one – in this war? Could it even achieve it in other theatres of war, like the Middle East?

Safe passage rather than truce

The whole idea of an Olympic truce (called “ekecheiria” in Greek) can be traced back to Antiquity. During this truce, “the athletes, artists and their families, as well as ordinary pilgrims, could travel in total safety to participate in or attend the Olympic Games and return afterwards to their respective countries,” the IOC explains on its websiteExternal link.

“It was more of a safe passage than a ceasefire or truce as we understand it today,” explains Patrick Clastres, a historian of the Olympic Games at the University of Lausanne. “In Greece at the time, there was constant warfare. The concept of peace was only invented after the Peloponnesian War, in the fourth century B.C.”

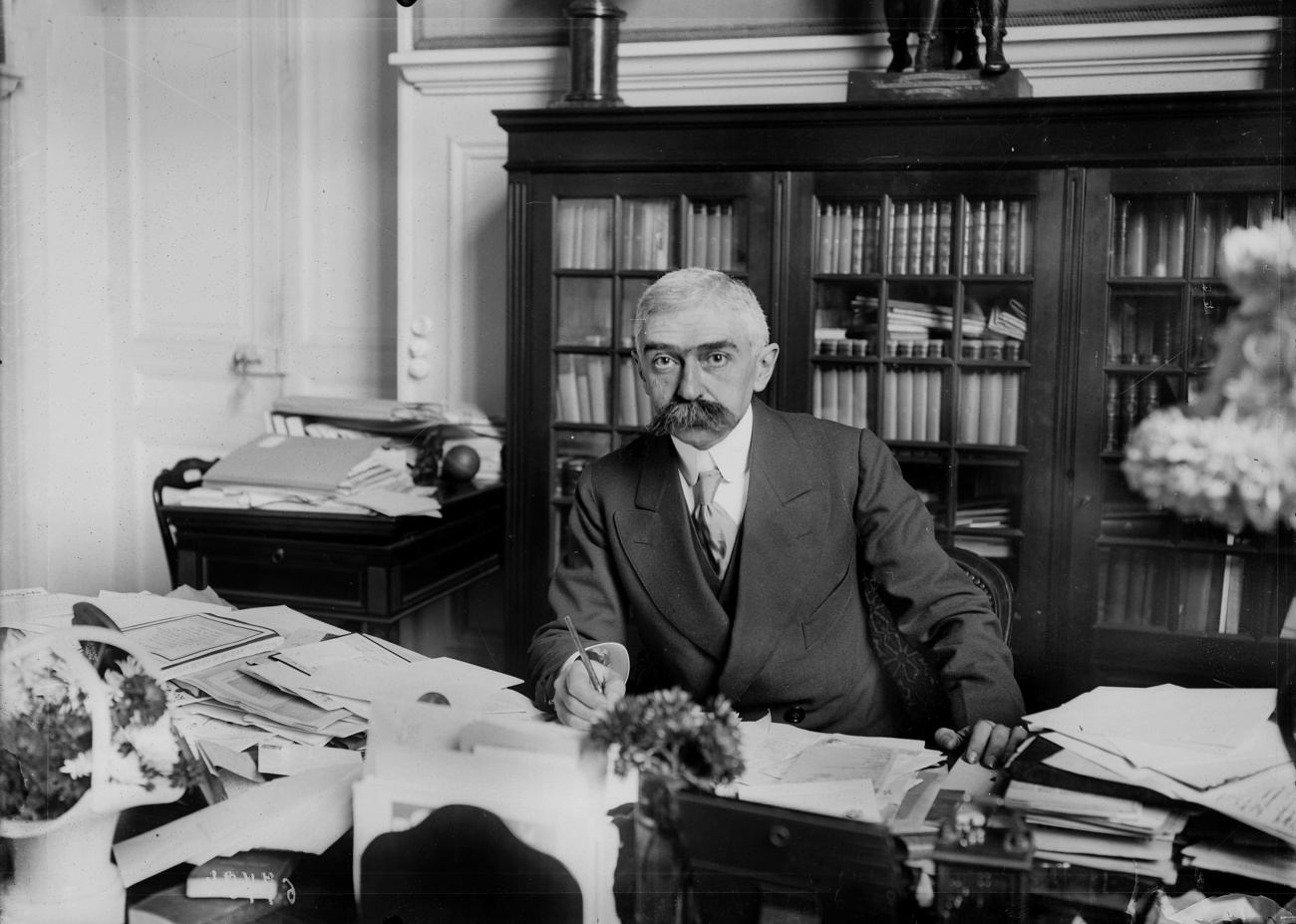

The truce is really an “invented tradition” that started with the revival of the Games in the late 19th century, says Clastres. At the Sorbonne Conference of 1892, which led to the founding of the modern Olympic Games, Pierre de Coubertin, who was to be the second president of the IOC (1896-1925), proclaimed the idea of peace through sport. “Let us export our rowers, runners and fencers,” he saidExternal link. “For therein lies the free trade of the future, and the day we do it, the cause of peace will have received a strong and vital ally.”

The world of amateur sport as Coubertin conceived it was in fact limited to a tiny social elite. “No one was thinking then that workers, women, or nations subject to colonialism might one day be participating in the Olympic Games,” says Clastres.

Five circles on a white background

Beginning with the first modern Games, held in Athens in 1896, geopolitical and military agendas clouded over the pacifist gospel of sport according to Coubertin. The holding of these first Games “needs to be understood as an episode in the Greeks’ effort to regain full national integrity and as a pursuit of the aims of the War of Independence that began in 1821,” writes historian Christina Koulouri in the catalogue for the current Louvre exhibition on the Olympic movement and its history. Dimitrios Vikelas, the first president of the IOC, was for a time a member of the National Society, a fiercely nationalist group in Greece.

No Olympic truce was forthcoming during the 20th century and its two world wars. But Coubertin continued to hope it would happen. He was, after all, the man behind the Olympic flag of five circles, symbolising the five continents, on a white background representing the truce, as Clastres points out.

Samaranch and his truce

In the 1990s, the Olympic movement was not in top form. There were boycotts, first by the Americans, then by the Russians. In 1992, in the midst of war in the former Yugoslavia, the UN forbade athletes from Serbia and Montenegro to participate in international sporting competitions, including the Barcelona Summer Games.

Juan Antonio Samaranch, president of the IOC at the time, was a Catalan. “He understood the danger to ‘his’ Olympic Games,” says Clastres. “He used all the resources of international diplomacy, Switzerland’s in particular, to get the UN to change its decision.”

The IOC, working closely with the UN, invented a neutral banner under which Serbians and Montenegrins could compete. It also proposed an Olympic truce for the Winter Games at Lillehammer in 1994. The IOC aspired to have a profile on the world political scene. At the same time, the UN was taking an interest in sport. This added up to a “win-win” relationship during the 1990s, when people still believed in the possibility of world peace and the “end of history”.

The UN went on to “make sport an important part of its soft power”, writes Julie Tribolo, a lecturer in public law at the University of Côte d’Azur. In 2001, the then secretary-general of the UN, Kofi Annan, named former Swiss president Adolf Ogi as his special adviser on sport for development and peace.

The foundation that disappeared

In 2000, the IOC even founded an International Olympic Truce Foundation (IOTF) and a similarly-named Centre (IOTC), with its seat in Lausanne and its offices in Athens. Oddly enough, it is now apparent from an internet search that the foundation has been deleted from the register of companies for canton Vaud.

“The IOC, which founded the IOTF, and the members of the board of the IOTF decided to dissolve the IOTF in 2020,” explains the IOC in Lausanne, “for operational reasons, in order to rationalise the work of the two organisations and transfer to one entity all the prerogatives, functions and activities to the IOTC.”

The IOTC organises camps focused on sport for peace. “These Greek-centred institutions were a concession from the IOC to Greece, which has always dreamed of being the permanent home of the Games,” says Clastres.

The impact over the last 30 years of the Olympic truce, which is discussed prior to each Games, is negligible. The Russo-Georgian war over South Ossetia and Abkhazia happened during the Beijing Games in 2008. Similarly, the Sotchi Winter Games in 2014 did not prevent Russian forces from seizing the Crimean peninsula. The Russians invaded Ukraine at the end of the Beijing Winter Games in 2022.

“And that’s before we’ve even mentioned other international conflicts, such as in Yemen, which have never been affected by this so-called truce,” says Aubin.

Adapted from French by Terence MacNamee/gw

More

Newsletters

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.