How Berlin made Ferdinand Hodler, and vice-versa

Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918), Switzerland's most famous "national painter", found his first success abroad in Berlin. Now he is back, and in context.

When Ferdinand Hodler’s painting “Die Nacht” (“Night”) was first shown in Geneva’s Musée Rath in 1891, its nude figures were deemed to “offend good morals” and provoked such a scandal that the painting had to be removed before the exhibition even opened.

Seven years later, the same work helped launch Hodler’s international career when it was displayed at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. Though Hodler never lived in Berlin, he visited several times and the city played a key role in his success.

“Berlin was a platform for Hodler, a place to network,” says Stefanie Heckmann, a curator at the Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art. “He planned it that way – he was strategic and clever.”

The Berlinische Galerie is exploring the Bern-born artist’s ties to the German capital and his reception there in a new exhibition, “Ferdinand Hodler and Modernist Berlin,” which opened on September 10 and runs until January 17, 2022.

The Swiss artist in the Berlin scene

Often viewed as Switzerland’s “national painter,” Hodler was last the subject of a major Berlin exhibition in 1983.

The latest show is a cooperation with the Kunstmuseum Bern, which has loaned more than 30 works to the museum as it doesn’t possess any Hodler paintings.

It is not a comprehensive retrospective: instead, it aims to place Hodler in the context of the Berlin art world by showing his work alongside that of his contemporaries in the city.

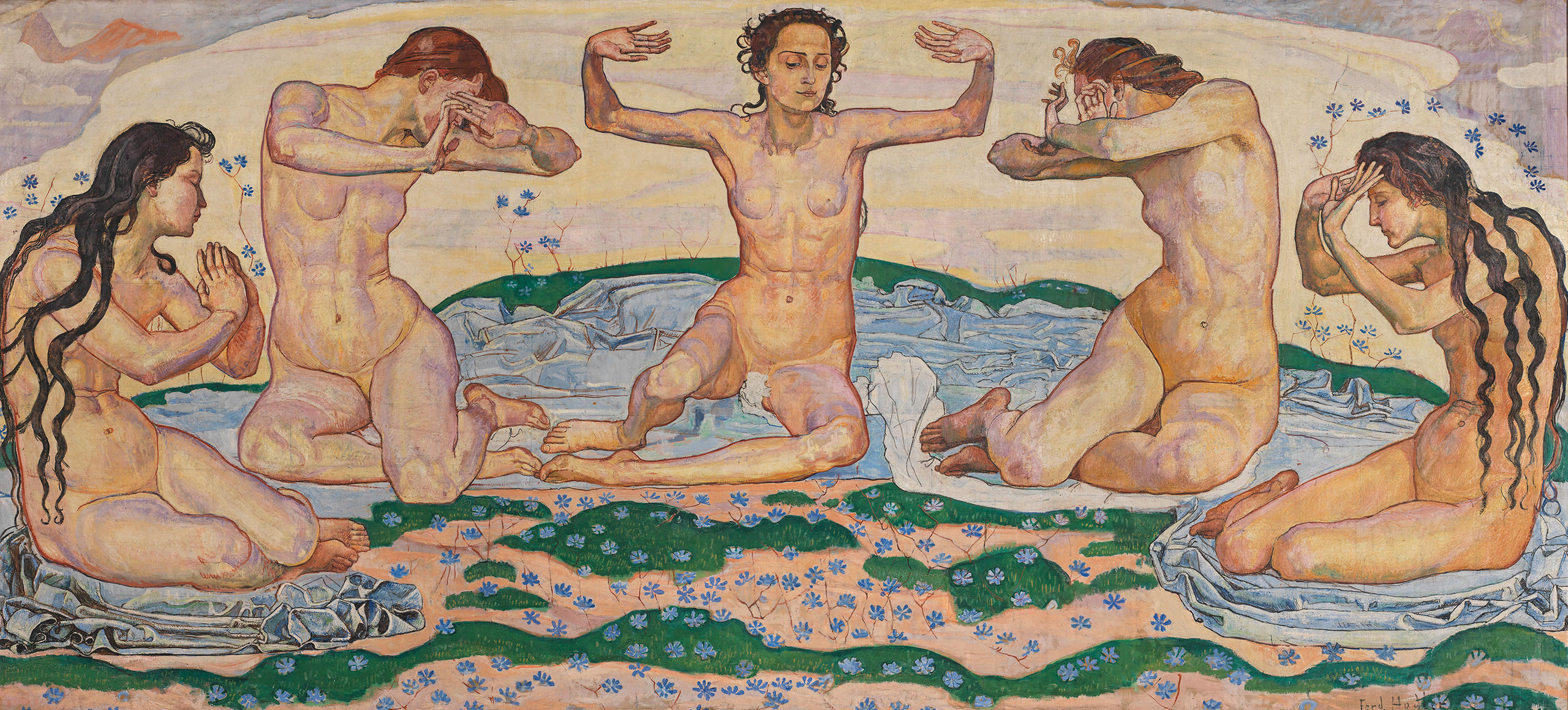

“Die Nacht,” a reflection on sleep and death, is among the highlights. It hangs in a large gallery at the end of the exhibition, opposite a similarly monumental work, “Der Tag” (“Day”, pictured below).

From 1898 until the outbreak of the First World War, Hodler held more than 40 exhibits in Berlin. In the early years of the 20th century, it was one of Europe’s most important art centres alongside Paris and Vienna.

The exhibition of “Die Nacht” was followed by shows at the Berlin Secession, an artists’ society of which Hodler became a member. His work was also displayed in the galleries of Fritz Gurlitt and Paul Cassirer, dealers who championed Impressionism and Modernism.

‘Hodler belongs to Germany’

By 1911, Hodler was a fixture on the Berlin art scene. As one critic wrote in 1911: “The tireless Secession presented Hodler’s paintings at every opportunity: he is known on all sides as the best monumental painter of the present…because Hodler belongs to Germany like Gottfried Keller.”

But he also polarised opinions. Though he was admired by established artists such as Lovis Corinth and Max Liebermann, the broader public took time to warm to him. Hodler’s enigmatic Symbolist portrayals of people were perhaps too mystical for the rational Prussians.

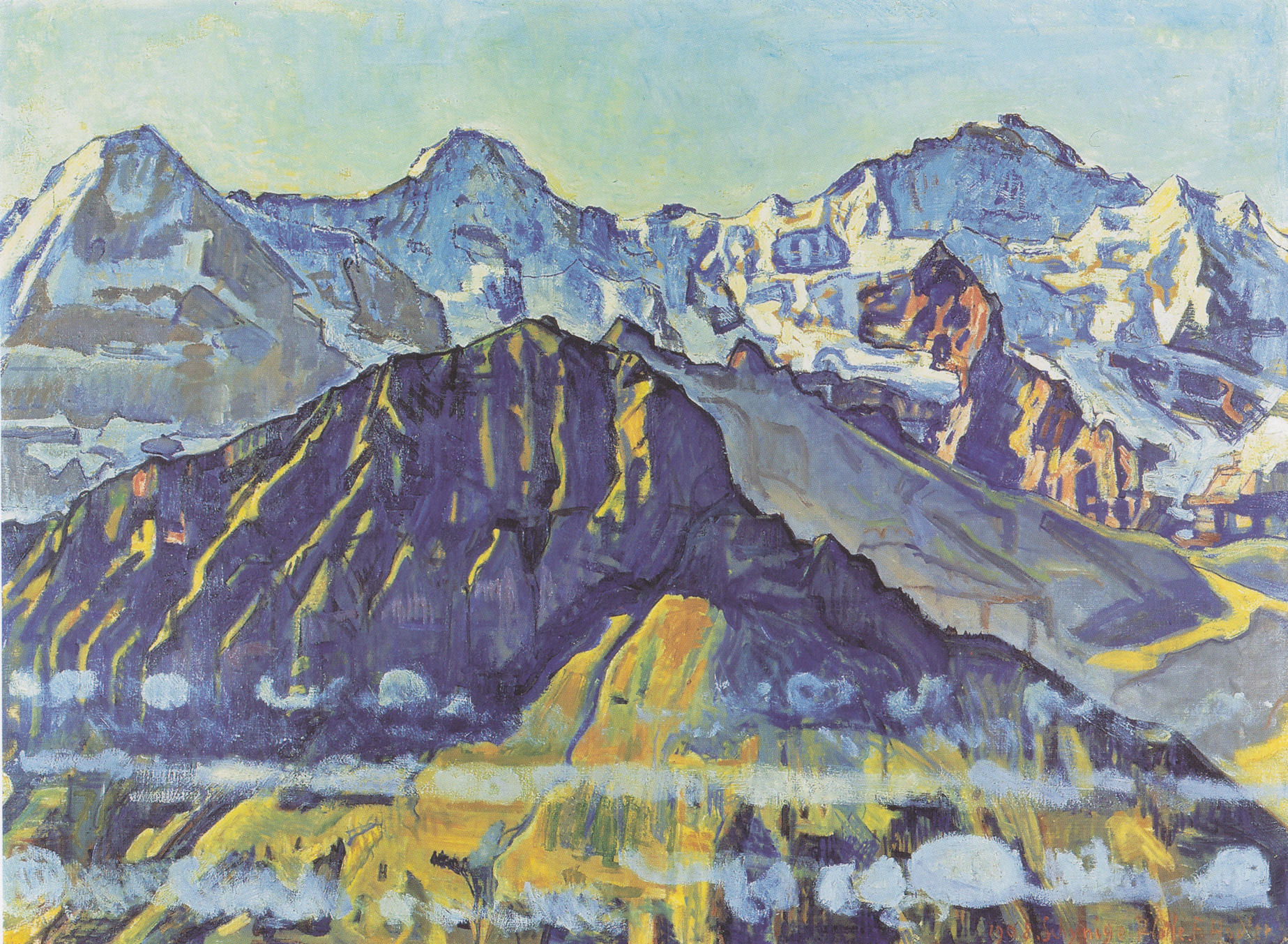

Hodler’s Alpine landscapes sold better, offering welcome escapism to residents of the crowded metropolis in flat, marshy northeastern Germany. Demand was such that he painted around 30 versions of “Lake Thun With Stockhorn Chain” from 1911 to 1914.

Bold, strange, primitive

The new exhibition illustrates how bold and pioneering Hodler’s works were in comparison with Berlin contemporaries and shows how they stood out as strange, or even “primitive,” as many reviewers commented.

His 1911 work, “Cheerful Woman,” is a vibrantly colourful view from behind an energetic, dancing figure in a red dress. The strong, dark contours of her body contrast dramatically with the orange-yellow background.

This painting is displayed alongside a much darker, 1901 painting by Eugen Spiro, “The Dancer Baladine.” Though similar in scale and subject matter, it is much more restrained in style and colour.

One of the most powerful works in the exhibition is Hodler’s 1912-1913 “Unanimity, The Orator,” an almost cartoon-like depiction of an impassioned campaigner for the Reformation.

One critic wrote in 1911 that “now it is becoming more and more obvious that Hodler is indeed a kind of Moses who can lead us into a new Promised Land”. Hodler was, as the critics noted, a trailblazer or even a “prophet” for the next generation, both in the dramatic intensity of his style and in his preoccupation with the inner life of his subjects.

A pioneer Expressionist

His German career came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of the First World War. Hodler was among a group of Geneva citizens and intellectuals who protested the shelling of Reims cathedral by German troops.

What became known as the “Hodler Affair” provoked a wave of indignation in Germany and he was expelled from a number of German artists’ associations.

But by the time of his death in May 1918, he had been largely rehabilitated. Berlin galleries began showing his work again. In autumn of that year, one critic praised the display of a “splendid early landscape” at Ferdinand Möller’s gallery and noted that Hodler’s “stock is rising.”

Even if by then, Expressionists such as the Brücke artists had taken some of his ideas further and produced images much more shocking to the Berlin bourgeoisie, younger painters — including Wassily Kandinsky — recognised Hodler’s contribution to the development of art.

The critic Theodor Däubler addressed his legacy in his 1918 obituary of the artist. “Hodler can be called one of the first Expressionists,” he wrote.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.