How do you build trust in new technologies?

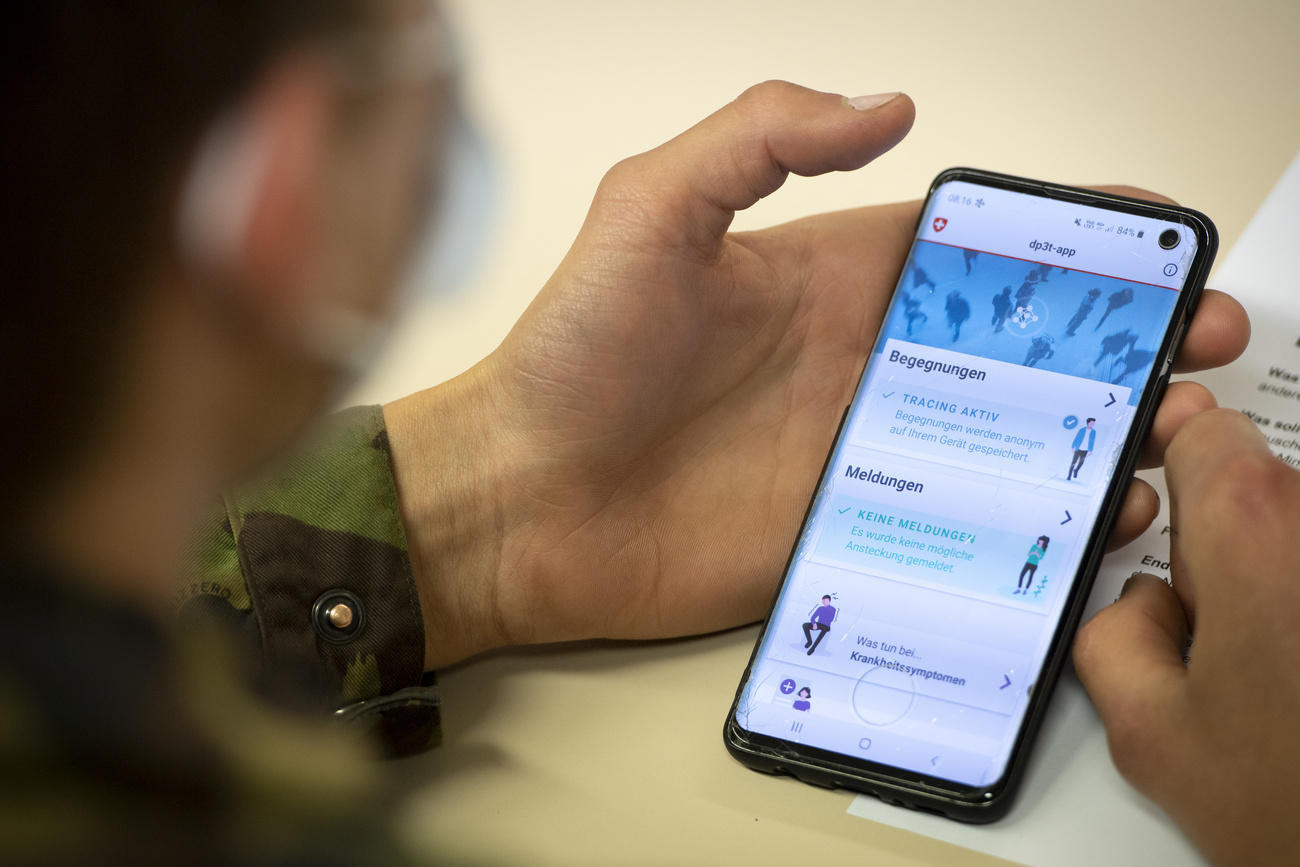

The coronavirus pandemic and controversy over the SwissCovid contact tracing app have highlighted the importance of boosting user confidence in new technologies. The “Swiss Digital Trust Label” is one solution aiming to ease this process.

In the digital age, the notion of ‘trust’ dominates the technological debate as never before. To be successful and effective, new technologies must be able to instil consumer confidence. Not only does consumption depend on this, but also the actual impact that technology has on society.

This issue inevitably influences the way that cutting-edge products and services are designed and developed. But the coronavirus pandemic has opened the Pandora’s box of the eternal conflict between ethics and innovation, placing civil society firmly at the heart of the debate.

How can innovation and ethics be combined?

So trust stops being the consequence and becomes the prerequisite of innovation. This leads to deeper reflection on the ethics and reliability of emerging technologies, two now indissoluble and essential concepts, especially in the world of artificial intelligence and digital solutions.

It raises key questions: How can one innovate while integrating ethical principles from the early stages of a new project? What criteria and rules should be adopted to protect the user, without hampering the innovative process?

The fear that having ‘too many rules’ will hinder the digital transformation of society and make it difficult to innovate is the subject of debate in the academic and business worlds. Already in 2014, the European Commission published a study on the complex and ambiguous relationship between regulation and innovation.

According to Jean-Daniel Strub, co-founder of ethix, the Swiss laboratory for ethical innovation supported by the Migros Engagement Fund, ethical considerations do not impinge on innovation, but rather help spur the development of more sustainable technologies, by confronting the main players with the risks of irresponsible progress in terms of their reputation, legality and the impact on civil society.

“Companies today cannot fail to approach innovation from an ethical perspective and make early investments in this respect. Being aware of the notion of ‘ethical risks’ is crucial in order to keep pace with a constantly evolving society,” says Strub.

Swiss Digital Trust Label

While a pragmatic assessment of the risks posed by technological advances that contradict the values of democratic and liberal societies is forcing small, medium and large enterprises, at least in the West, to address the issue of ethics, the biggest challenge nonetheless remains: turning the debate into concrete actions that will give the system a positive shock.

With this in mind, the Swiss Digital Initiative – which was presented at the first Swiss Global Digital Summit in September 2019 – launched its first project, the Swiss Digital Trust Label, at the end of last year. Its aim is to promote the responsible use of new technologies through a multi-faceted and pragmatic approach. According to the Swiss Digital Initiative’s director, Niniane Paeffgen, the idea is to give users more information on digital services, thereby creating transparency and ensuring respect for ethical values.

“At the same time, we want to help guarantee that ethical and responsible behaviour also becomes a competitive advantage for businesses. This label seeks to balance the asymmetry of information and power that exists today between people and the economy,” Paeffgen explains.

Similar initiatives have already emerged at the international level. In Switzerland, the project was initiated by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), and is being carried out thanks to collaboration by an interdisciplinary group of experts from the EPFL, the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, the universities of Geneva and Zurich and different players from the world of industry, who are all members of the digitalswitzerland network.

Can we trust a label?

While the existence of a label could certainly encourage companies to adopt responsible behaviour, in order not to be cut out of the market, questions remain about how to ensure that the initiative does not turn into a business.

“The Swiss Digital Initiative is a non-profit organisation. Our mission is to create high-quality content and to give international players the possibility of taking it on to the next level,” Paeffgen explains.

The label is currently in the development stage. A public consultation was recently initiated in order to stimulate an open debate in preparation for the launch of the label, scheduled for spring/summer 2021. However, some non-minor issues have still not been resolved, such as the cost of obtaining the label, reinvestment of the profits, and how to guarantee objectivity and transparency in awarding it.

According to the Swiss Digital Initiative, compliance with the criteria will be certified by an external and independent verification body, such as SGS Société Générale de Surveillance (General Society of Surveillance), a Swiss multinational headquartered in Geneva that provides inspection and certification services. So does this mean that we can trust the label?

An initiative that could work very well or very badly

Professor Effy Vayena, director of the Health Ethics and Policy Lab at ETH Zurich, welcomes the initiative, but stresses the importance of establishing the right criteria for it to be effective. “When selecting the criteria, pragmatism and feasibility are key. Initiatives of this kind can work very well or very badly, depending on the approach chosen,” says Vayena.

Another point to consider is the still widespread distrust among those sceptical of the ‘label business’, accompanied by the fear of rising costs for consumers. “On the other hand, what’s the alternative?” questions Christoph Heitz, president of the Swiss Alliance for Data-Intensive Services, who is leading a project to draw up a code of ethics for data-based activities.

In Heitz’s view, the basic merit of labels is to generate positive dynamics within society, without necessarily having to resort to legal obligations. “Labels cannot replace laws, but at the same time legislation cannot address all the problems. I think the good thing is that these initiatives raise awareness and set standards,” says Heitz.

However, it is still difficult to conceive that, in an uncertain or even non-existent regulatory framework, ethical initiatives can mark a real turning point for society. How would it be, then, if good ideas went hand in hand with good laws?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!