How the Swiss extract gold from rubbish

Switzerland is the global leader in metal recycling, a lucrative business that attracts international interest. We visit a pioneering Swiss waste disposal and recycling plant with a delegation from Japan.

Daniel Böni reaches into the container. “There is always something,” he says and pulls out three boule balls. “This one would be too rusty, but the other two could still be used for a game,” he says, looking at the three balls that have somehow ended up in the residual waste bin. The fact that the boule balls have not been recycled is a blow to a country which is proud of its recycling record in many areas.

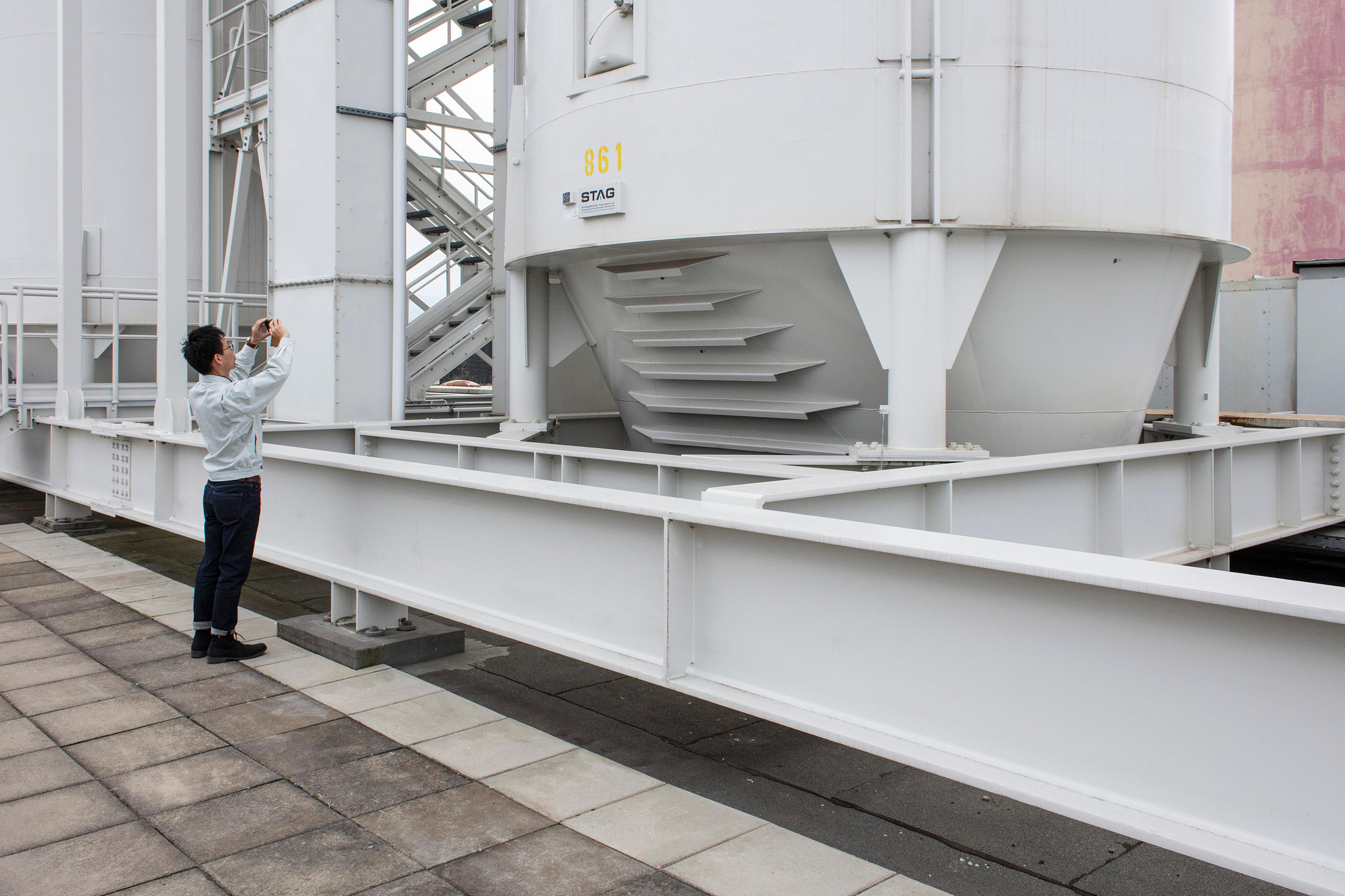

Böni, managing director of the KEZO Hinwil disposal and recycling plant, takes the Japanese delegation from global cleantech company Hitachi Zosen on a guided tour. KEZO Hinwil is a pioneer in metal recycling, burning household and industrial waste and filtering it for precious materials. Items like the boule balls are actually not that interesting; the search through the bottom ash concentrates more on valuable metals like aluminium, platinum and gold.

“Sometimes we even find a gold chain or a very small gold bar,” he explains. “This usually happens when granny’s hiding place was a bit too sophisticated. During the house clearing such hidden treasures often end up in the bin.” But all that glitters is not gold, and the most valuable waste in metal recycling is electronic waste. It contains particles of precious metals.

Lucrative business

“At the current gold price it’s very lucrative,” Böni says with a smile. But the metal business appears to be worthwhile overall. “Had I taken the revenues from the metal sales instead of my salary, I would have fared a lot better.”

However, metal recycling is not just economically interesting, it is also ecologically sound. “It’s at least as important as generating energy from burning waste,” he says.

When the KEZO plant opened 15 years ago, nobody knew whether the system of metal recycling would work. There are now five metal recycling plants across Switzerland using the same system. Two more are planned. Soon, all Swiss waste processing plants will filter waste for gold, which is unheard of in other countries.

“Our system is unique and is not used anywhere else in the world,” says Böni, who is obviously convinced about the Swiss system.

Exception rather than rule

Everything that does not get recycled is burnt in KEZO Hinwil. Waste incineration is the norm in Switzerland, but globally speaking it is rather an exception.

More

Rubbish and recycling

According to the World Bank, almost 40% of waste is disposed of in landfills around the world, while only 11% is incinerated for final disposal. In North America, for example, more than half of waste ends up in landfills, while Japan follows the Swiss example. Only 1% of Japan’s municipal waste is disposed of in landfills, 80% is incinerated. These and other figures were published in the 2018 World Bank report What a Waste 2.0, which illustrates that the Japanese delegates are already familiar with the system.

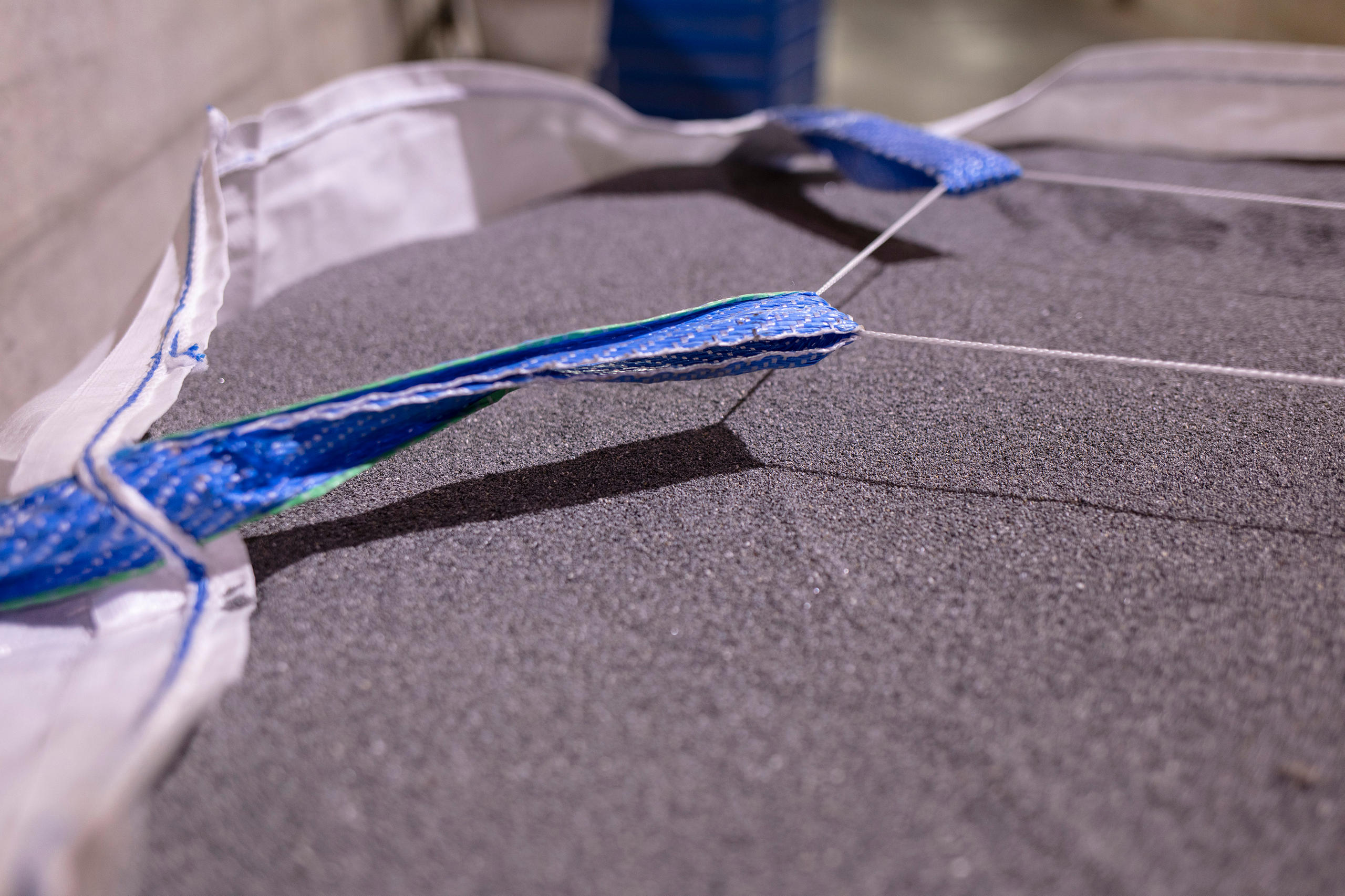

Böni explains that recovering metals from bottom ash has significant advantages. “The metal shrinks in the process, which makes it a lot easier to separate the individual pieces.” Pieces of aluminium foil, for example, shrivel and turn into small lumps.

According to Böni, another even more important factor is the dry processing of the bottom ash. The filter machines get clogged up if the raw materials are even slightly moist.

More

How much trash is tossed – and recycled – in Switzerland?

Dust-free dry ash

There are some reservations against the dry processing of bottom ash. Some in the industry argue that dry ash creates dust which is a health hazard to the workers. But the machines at the Hinwil plant seem to be leakproof as no particles permeate the inspection holes.

Böni points out that the plant is dust-free, a fact his visitors affirm with a nod. Dry processing of bottom ash is the exception rather than the rule, and all five Swiss metal recycling plants apply this system. Sweden has one dry-processing plant while Italy has six. “The Italians use this system to save water,“ Böni explains.

In the first step of the process all ferrous metals are removed from the incinerator bottom ash with a magnetic separation device. In the second step, items like the boule balls or vacuum cleaner motors are handpicked from the ash. Once this is done, the remaining ash is fed into an automatic system that runs across several buildings and floors and consists of conveyor belts and filters with tiny holes that allow for very fine filtration.

The entire process is extremely noisy with engines roaring during every step. But the sound of the particles flying against the pipes and inspection holes turns into a trickle as the particles get finer.

Pot of gold

“It’s a production process,” Böni says. “We make metal.” The plant produces around 1.2 tonnes of pure aluminium granulate a day. As aluminium is lighter than other metals, the machines can separate the aluminium pieces by their weight. About 540 tonnes of precious metal are extracted from waste a year.

Very carefully, the visitors reach into the open container and scoop some of the glittering but sharp-edged material onto their hands. Is this really gold?

There is no such thing as a pot of gold at the Hinwil plant. The precious materials are resold as a valuable mix of copper, palladium and gold. The market price for aluminium and other metals determines the business. “Sometimes it feels like paradise, sometimes it’s difficult,” Böni explains.

Metal prices are important for the business, but Böni says that, ecologically speaking, this kind of metal processing saves huge amounts of CO2 equivalents. Recycling is not as energy intensive as mining, he says.

However, the remaining ash is disposed of in landfills which Simon Retailleau, who works for Hitachi Zosen’s Zurich branch, thinks is a cause for criticism. “We could use the remaining ash for cement processing or road construction, like they do in other countries,” he says. Retailleau finds it difficult to understand why this is not the case in Switzerland.

More

Should the Swiss stop sorting their trash?

The Federal Office for the Environment argues that the residues from the waste incineration plant exceed the limit values for cement production, and they cannot be watered down.

“So we need landfills in Switzerland to avoid that contaminated material […] entering the environment,” the federal office explains. It points out that around six million tonnes of “dismantled waste” and 12 million tonnes of “excavation material” that do not exceed the limit values and could be used for construction also end up in landfills in Switzerland every year.

Gold rush in Japan

The visitors from Japan seem to be very impressed by what they see – their comments and exclamations range from “interesting” to “very, very interesting”.

Sachiko Oochi, who heads Hitachi Zosen’s research unit, leads the delegation. After the tour, she says the dimensions exceeded her expectations. “I was surprised by the sheer size of the plant.”

Oochi says she learnt a lot during the tour but thinks the bottom ash in Japan contains different materials. “We need to examine carefully whether we can follow suit in Japan, but I think it would be worth considering.”

Whether the Japanese will soon be rummaging through their own rubbish in search for gold remains to be seen.

Edited by Marc Leutenegger, Translated from German by Billi Bierling

More

Why don’t the Swiss recycle more plastic?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.