In the Swiss Alps, solar power takes to the water

The world’s first high-altitude floating solar power plant is now operating – in the Swiss Alps. According to experts in the field, this technology could become a major part of the photovoltaic industry worldwide.

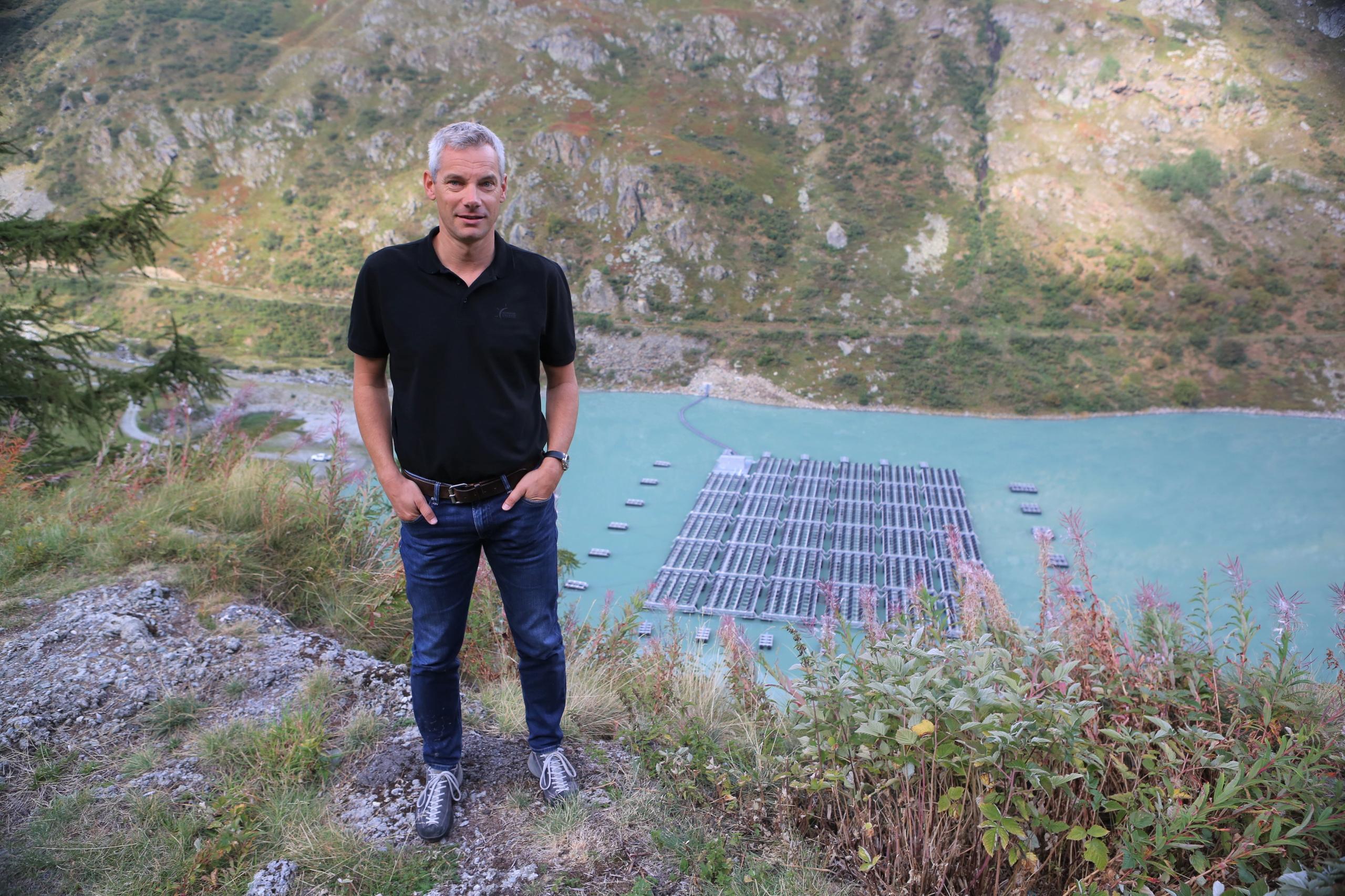

“The idea started over a coffee,” Guillaume Fuchs recalls. “We were wondering how reservoir lakes could be used to produce more power. That was in 2013, and there were already a few projects on the go for floating solar power plants. But at that point, there was none in an Alpine environment.”

We meet in Bourg-St-Pierre, a village in Canton Valais on the road to the Great St-Bernard Pass, between Switzerland and Italy. A French-Swiss dual citizen, Fuchs qualified as a mechanical engineer and worked in the auto industry before getting into the field of renewable energies.

“I wanted a job in a more sustainable sector,” he says. He now works for Romande Energie, the main supplier of electricity in French-speaking Switzerland.

We travel a few kilometres southwards, into a valley that is gradually starting to take on an autumn glow. After a few minutes we get to the Lac des Toules, a man-made reservoir used for hydroelectric production at an altitude of 1,810 metres (5,938 ft). This is where Fuchs developed his project, the first floating photovoltaic installation in the Alps.

“Here you find pretty extreme conditions: there’s wind, ice, snow, and temperatures ranging from -25°C [-13°F] to +30°C,” he says. “I was lucky enough to be working with people who didn’t talk about problems but about solutions.”

More electricity than in valley

The solar plant at Lac des Toules consists of 1,400 panels, laid on 36 floating structures made of aluminium and polyethylene plastic anchored to the bottom of the lake. Current production exceeds 800,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) per year, which is the equivalent of consumption for about 220 households.

Despite a considerable up-front investment of CHF2.35 million ($2.6 million) – more than what a similar installation on dry land would cost, thanks to extra costs associated with rafts and anchors – a photovoltaic installation on a man-made lake at a high altitude has several advantages.

“The atmosphere is a bit thinner and so UV rays are more intense,” Fuchs explains. “The panels are actually more effective at low temperatures, and we can even use the reflected light from the snow.”

Using two-sided panels, which are fitted with photovoltaic cells both front and back, means they can also use light reflected from the surface of the water, which adds to the electrical yield.

“Compared to an installation of the same dimensions down in the valley, we produce about 50% more electricity up here,” he points out.

Resistant to snow and ice

Beginning operation in December 2019, the solar power plant in the Alps got through its first winter successfully, Fuchs says. The problem with ice, which can be as thick as 60cm on the lake, was resolved using floats, which raise the structure whenever the surface of the water freezes over. When the lake is completely emptied at the end of March, the platforms come to rest on the bottom, which is flattened out.

The structure can sustain up to 50cm of snow. If the snowfall is heavier, the snow slips off the panels as soon as the sun begins to shine.

“The back of the panel is what produces electricity,” Fuchs explains. “So they warm up, and the snow just slips off. After doing several tests we came to the conclusion that a slope of 37° on the panels would be enough to get the snow off, without compromising the efficiency of the photovoltaic cells.”

Future of solar power

The first floating solar installation was built in 2007 in Japan, and it was followed by projects in other countries, including France, Italy, South Korea, Spain and the United States. Currently, more than a hundred floating plants are operating around the world and the capacity has been increasing since 2014.

The panels can be placed on all kinds of bodies of water, from the industrial (disused mines) to the open sea. The world’s biggest installation of this kind is now in Anhui province, China, while the biggest one in Europe is in Piolenc, in the south of France (with 47,000 photovoltaic panels).

According to players in the sector, floating stations are really the future of solar power because the water cools the panels, increasing their yield. Furthermore, they resolve the issue of land use because they don’t take away any space from agriculture or construction.

This kind of solar power is likely to expand in many parts of the world, according to a reportExternal link from the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore and the World Bank.

Panels on existing structures

Fuchs and Romande Energie are hoping to take the pilot project further. If the experimental phase confirms what has been found so far, the first floating solar plant in the Alps will be extended to cover about a third of the Lac des Toules. The facility will then be able to provide 22 million kWh per year, meeting the needs of 8,000 households.

This is not all. Fuchs hopes to put his technology on other lakes in Switzerland and beyond. But there are some prerequisites.

“The lake has to be accessible – it can’t be situated in a protected area, and of course it needs to be in a location with solar potential,” he says. “A study of ours found that there may be about ten lakes in the Swiss Alps that could accommodate that kind of infrastructure.”

The project on the Lac des Toules was approved by the local chapter of the World Wildlife Fund, as it is a site already used for power production, and one where fauna and flora are unable to thrive, since the lake is emptied once a year.

But pending a study on the installation’s effect on phytoplankton (microscopic marine algae), the environmental groups would prefer to see other solutions. Before covering over large parts of man-made lakes, engineers should consider built-up areas with large populations and install panels on existing infrastructure, such as roofs, façades and car parks, Michael Casanova of Pro Natura told the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.