Donor fatigue looms over humanitarian aid in Ukraine after two years of war

Two years after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the humanitarian situation in the country remains critical. For the first time, the United Nations fears that it will not get enough funding to assist Ukrainians affected by the war.

“It’s quite shocking how Ukraine has fallen off the news headlines,” says Sarah Hilding. Speaking from Kyiv, the head of the United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Ukraine does not hide her concern: “Funding is one of our main worries.”

Although the UN received enough funding in 2023 to cover 69% of needs in the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, the organisation now fears that funds will dry up, particularly as the catastrophic situation in Gaza continues to overshadow the crisis in Ukraine.

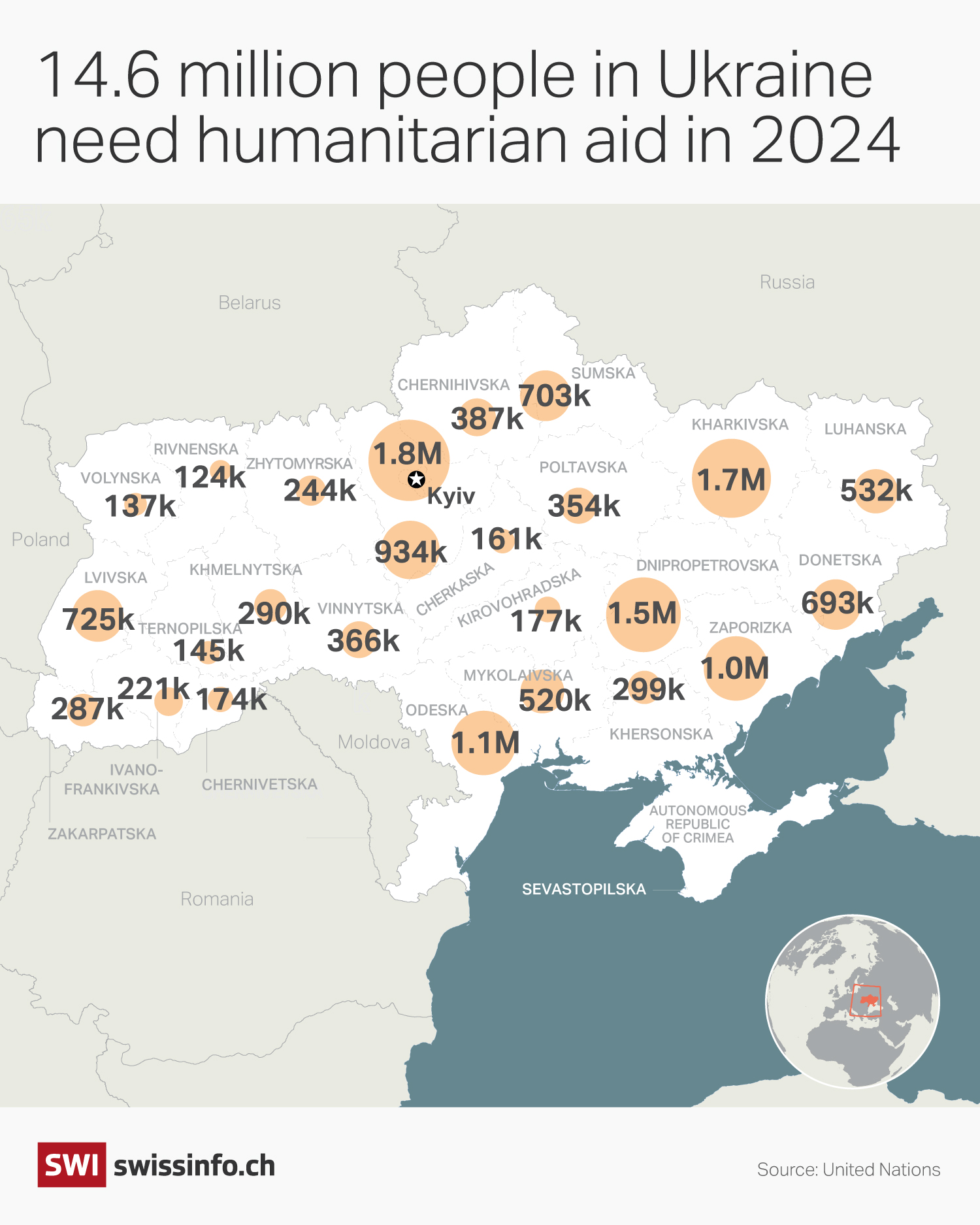

A full two years after the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, humanitarian needs in the country remain high. According to the UN, around 40% of the population – 14.6 million people – will require assistance this year.

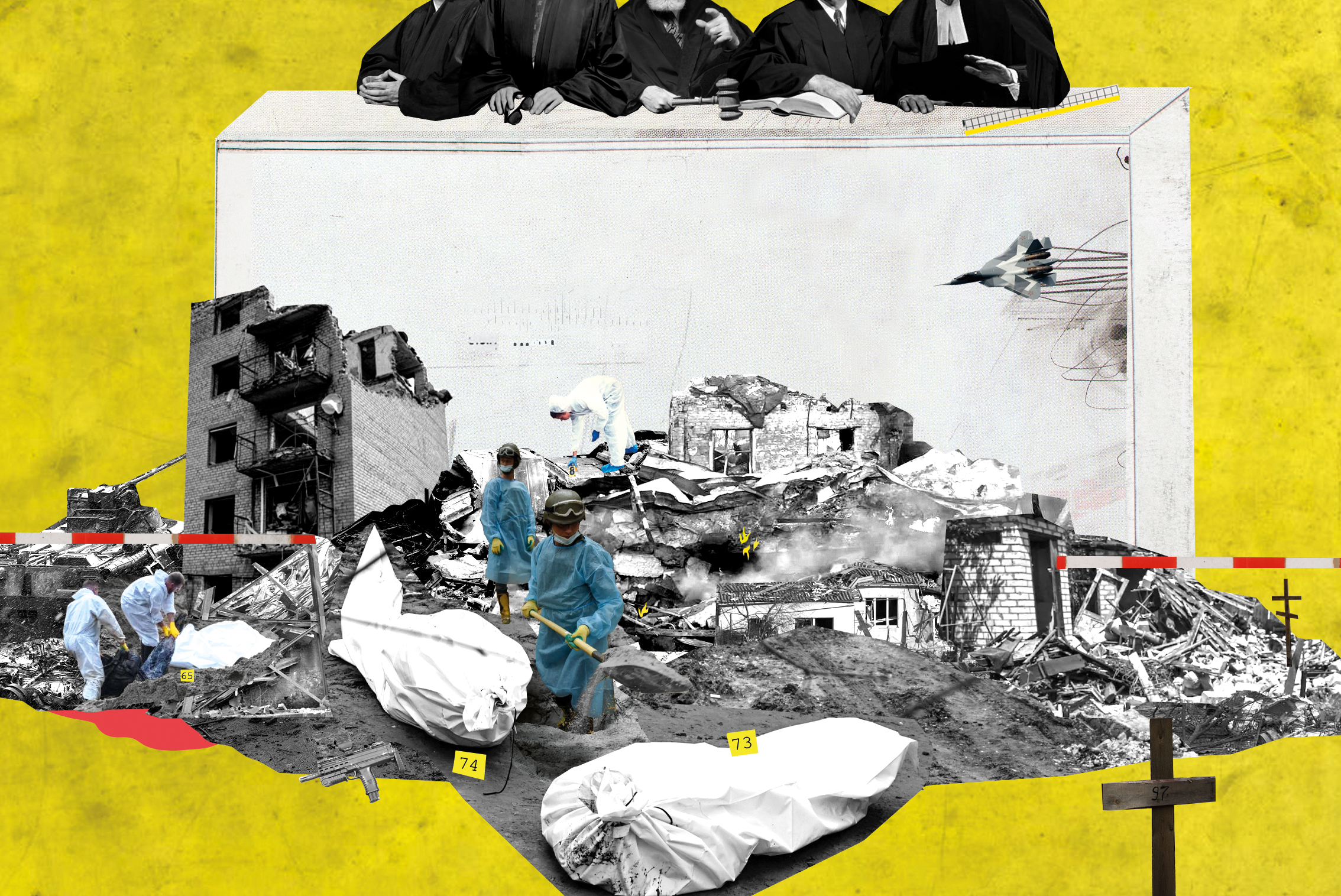

“The war really is relentless,” says Hilding. “Every single day civilians are impacted, people are killed, hospitals are destroyed or damaged, as are schools and other civilian infrastructure.” As an example, she recounts spending her morning in a shelter because of an air-raid alert.

The front line has barely moved in the last year, but the whole of Ukraine continues to be regularly targeted by waves of missiles and drones. These attacks have intensified since December 2023.

Two years on, needs are growing

Humanitarian needs are highest in the regions close to the fighting, in the east and south of Ukraine. In these territories, which include those under Russian control to which UN agencies have no access, more than 3 million people need help. In the centre and west, some 4 million displaced people are also particularly vulnerable, according to the UN.

“Frontline communities are exhausted. Their resources are drained,” says Hilding. Many of the people remaining in these regions are elderly. After two years of war, they have depleted their savings and rely on humanitarian aid to get water, food, and medical care. As time goes by, more and more people find themselves in this situation. “Because of the prolonged nature of this war, the needs of people who have remained have grown,” she adds.

Then there are the people who fled at the start of the invasion and are now returning to find their homes have been destroyed or that the land they farmed is still mined.

The UN’s coordinated aid plan for Ukraine in 2024 will cost $3.1 billion (CHF2.72 billion) to cover the needs of 8.5 million people. This is less than last year’s total of $3.9 billion, which reflects the UN’s goal to prioritise the most vulnerable people. This effort has been made in light of concerns about the generosity of donor countries.

Anticipating a funding gap

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), an international NGO present in Ukraine which receives a share of UN funding, is also expecting a funding gap in 2024.

“Things can get catastrophic very quickly if funding drops suddenly,” warns Athena Rayburn, the NRC’s regional head of advocacy for Ukraine. It is therefore important, she says, for humanitarian agencies to ensure that their response is as sustainable as possible. One of the NRC’s priorities this year will be to work with the Ukrainian government and civil society to determine which services could be delegated to them if humanitarian organisations were to run out of money.

In the event of a funding gap, tough choices will have to be made. Some people will be deprived of vital aid. “This, for someone like me and for my colleagues, is heartbreaking. We see that people need help. We should be able to tell their story in a compelling way so that donors understand that when we say we need the money, we really do,” says Hilding.

Avoiding parallel systems

Two years on, the conflict appears to be stalling. In a country like Ukraine, where the government benefits from the financial support of major international partners, is large-scale humanitarian action still justified?

“I would say so. From the moment there are emergency situations, people living in precarious situations, who are suffering from major violence, I think it’s entirely justified,” says Karl Blanchet, Director of the joint Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies of the University of Geneva and the Geneva Graduate Institute.

According to him, it is too early for development actors such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund or the OECD to invest in the reconstruction of the country, as there are still too many uncertainties linked to the war.

However, the expert underlines the risk that, in the long term, humanitarian aid creates dependency and generates parallel service systems. For example, a perfectly functional hospital run by an international NGO could emerge a few kilometres from another health facility run by the Ukrainian government, where staff and medicines are in short supply.

Trump’s shadow

The year 2024 could prove particularly difficult for humanitarian aid in Ukraine. As Western support begins to crumble, notably in the United States where Congress is blocking a new $60 billion aid package – mainly military – for Kyiv, the shadow of the US presidential election in November hangs over the humanitarian community.

Former president Donald Trump is vehemently opposed to aid for Ukraine and could decide, if elected, to reduce American support for the country, which would have an impact on the conflict and on the work of humanitarian aid staff. Known during his previous term in office for his contempt for multilateral cooperation, Trump could also seek to cut the contribution of the US – the largest donor country – to the UN humanitarian system.

“Elections or no elections, we are already worried about the fact that we’re not going to get enough funding,” says Hilding, who declines to comment on national politics. “I just hope that regardless of who’s in power anywhere in the world, humanity will show through in terms of funding for humanitarian operations.”

At a time when crises around the world – from Gaza to Sudan and Yemen – are multiplying without being resolved, and the gap between funding and needs continues to widen, many emergency situations are chronically underfunded. Could Ukraine one day join the ranks of these so-called forgotten crises?

“It’s very possible,” says Blanchet, although he stresses that the country has the advantage of being in Europe, and therefore close to the main donors. “Ukraine is less likely to become a forgotten crisis. But at some point, there’s going to be widespread [donor] fatigue.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

>>> Read our article on the phenomenon of forgotten crises, from the DRC to Myanmar and Afghanistan:

More

How to break the cycle of underfunding for forgotten humanitarian crises

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.