From pandemics to climate change, can we work together?

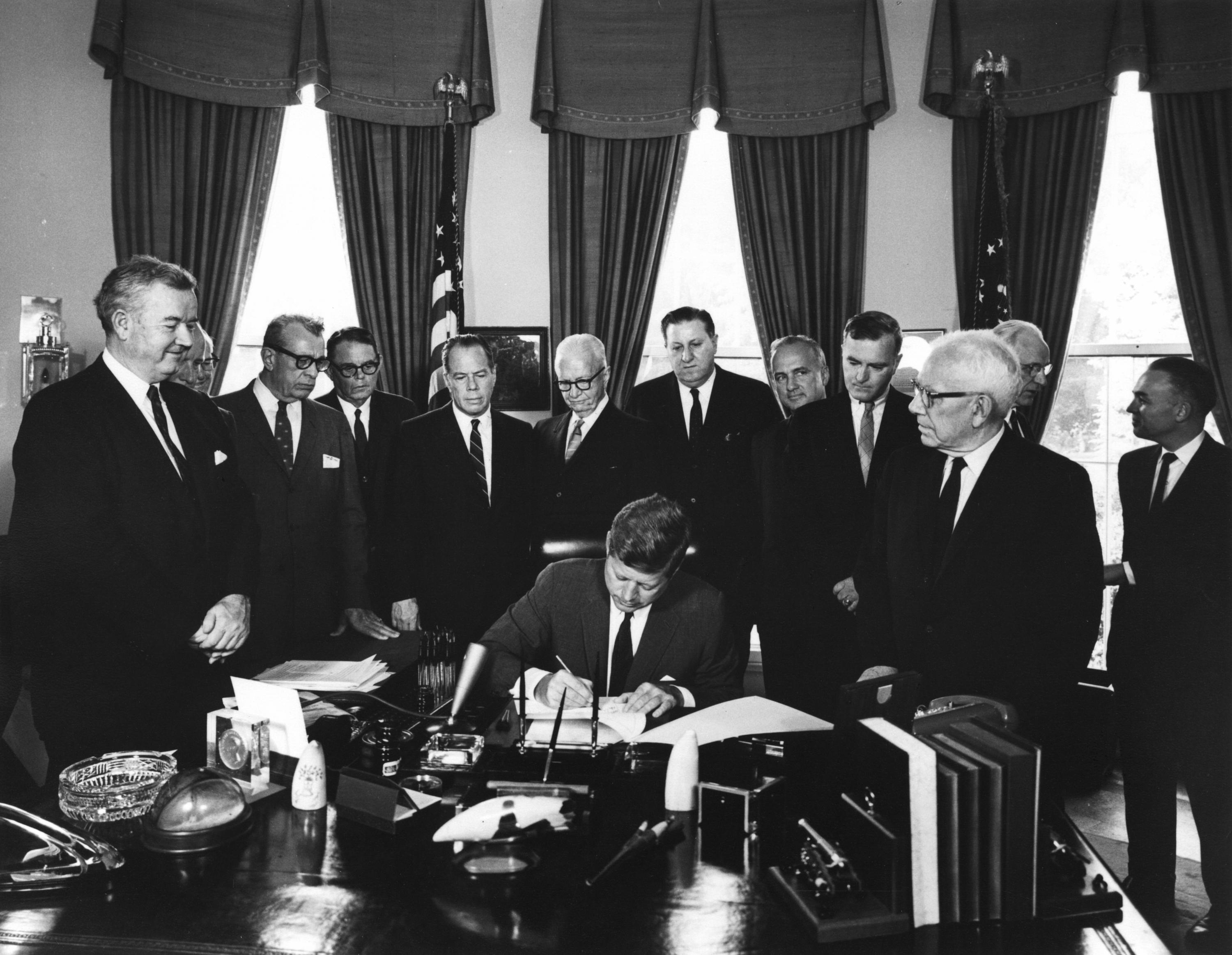

Last week, member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) rose to their feet for an extended standing ovation. The long awaited, and much negotiated, pandemic accord had been passed.

It was hailed as a historic moment; global treaties are always tricky, and this was the first agreed by the Geneva-based WHO since the tobacco control convention more than 20 years ago.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the head of the WHO, said the agreement, designed to prevent the uncertainty, vaccine inequity, and lockdowns of Covid-19, meant “the world is safer today”. But how significant is it really? And is this a genuine sign that countries can work together for the common good? What about other challenges, such as climate change, where cooperation is essential? That’s our topic on Inside Geneva this week.

More

Inside Geneva: pandemics and climate change, can multilateralism still work?

The pandemic agreement was negotiated and approved in record time – three years may sound long to most of us, but it’s a sprint in treaty terms – but that speed and unity means some key elements are missing. There is broad accord on coordinating global preparedness and response, and even some positive words on skill sharing and equitable access to medicines.

But agreement on the thorny issue of “pathogen access and benefit sharing” has been delayed. Primarily poorer countries argued hard that if they maintain vigilance on emerging viruses, and rapidly identify and share the details with pharmaceutical companies in wealthy countries, they should expect to benefit from fair access to life-saving treatments.

More

Pandemic treaty comes as welcome sign of multilateralism

Major step forward

Former UN Human Rights Commissioner Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein believes the treaty is “a major step forward”, arguing that failure to agree would have been a dangerous setback, leaving the world divided, and unprepared for, the inevitable next pandemic.

Al Hussein provides Inside Geneva with a fascinating behind-the-scenes view of the negotiations towards the pandemic agreement. In his current role as a member of The Elders (the body founded by Nelson Mandela to bring together global leaders to work for peace, justice, human rights and a sustainable planet) he had a quiet role as a facilitator, trying to bridge differences between member states.

“What we noticed in the negotiations is a very strong pushback, principally by the African countries, on this idea that they would make available their sequence data,” he tells Inside Geneva.

“They would sequence a mutation, as they did with the Omicron variant of Covid, and they upload the genetic sequence data. And for this efficient and rapid action, they received little in the way of therapeutics, diagnostics and vaccines.”

Al Hussein believes the discussions, and the promise to move forwards on equitable access and benefit sharing, can only be positive, and he thinks it will work. Market forces may even drive cooperation, he suggests, because big pharmaceutical companies in wealthy countries will need the pathogen sequences, and they will want access to huge emerging markets in the Global South.

Elephant in the room

But there’s still an elephant in the room: the United States has left the World Health Organization and took no part in the pandemic agreement. Can a global health treaty function without a major superpower? One with a huge pharmaceutical industry? Al Hussein thinks it can. The lack of the US may not, at the moment, “make much difference”, he says. And if everyone else works together, the US may realise it’s not ideal to be shut out of scientific knowledge and to be shut out of the profitable race to develop new medicines the entire planet needs.

We can all hope al Hussein’s optimism is justified. But there’s another big challenge – existential, some argue – that needs global cooperation, and that’s climate change. Here the US is not the elephant in the room, but the rogue elephant trampling over years of hard work aimed at reducing the speed of global warming, amid clear scientific evidence that rising temperatures are already having disastrous consequences, from floods, to droughts, to melting glaciers.

Our second guest on Inside Geneva is Peter Schwartzstein, climate security specialist, and author of a book on climate change-related conflict, The Heat and the Fury: On the Frontlines of Climate Violence. He describes the time since President Trump’s re-election as “continual, mostly very unhappy whiplash. In the climate space, the Trump administration is going out of its way to kill both climate language, but also anything even tangentially related to climate programming”.

Schwartzstein’s book details fascinating, but hugely worrying, links between climate change and conflict. Farmers in Bangladesh for example, pushed off their land by rising sea levels, turned to fishing instead. But the waters are lawless, pirates have operated in the region for decades. Now climate change has given the pirate business a boost, as they ply their trade taking the new fishermen hostage and extorting money from their desperate families.

Schwartzstein, who has done extensive research in Iraq and Syria, even suggests that “ISIS […] benefited tremendously from collapsing agricultural conditions to bolster its ranks. The idea being that without climate and wider environmental-induced difficulties in farming areas, the group never would have been able to grow as large and as deadly as it soon became”.

Learning the hard way

Schwartzstein fears that, as with Covid-19, we may only learn the hard way that global unity around climate change is essential. “We’re up against a ticking clock,” he warns Inside Geneva. “Even though we’ve enjoyed successes in the past, even though the renewables rollout is going rather well, it’s all too little, too late from the point of view of avoiding genuinely dangerous degrees of warming.”

He suggests another disastrous summer of wildfires, droughts, floods and sheer unbearable heat may finally concentrate our minds. But will that mental focus penetrate to the gilded, air-conditioned salons of the White House? Here al Hussein, who also offers The Elders’ quiet diplomacy on climate change, has some words of advice to leaders who choose to deny the scientific facts.

“Their children and grandchildren will have to deal with abominable and extreme heat levels and forest fires and fierce hurricanes and no trade and collapsed economies and extreme food security and complete anarchy,” he says. “Is this what they wish for their children? What form of love is that?”

And while al Hussein, based on the work he does behind the scenes tackling those big global challenges, does retain some optimism that people with integrity and vision, from business to academia as well as politics, will step up to the challenges, he also occasionally entertains a darker scenario.

“I sometimes imagine engraving our epitaph, he tells us. “I’m sure it’s going to be something like ‘here lies humanity […] but the markets were up’.”

Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that. Listen to Inside Geneva for a fascinating discussion.

vm/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.