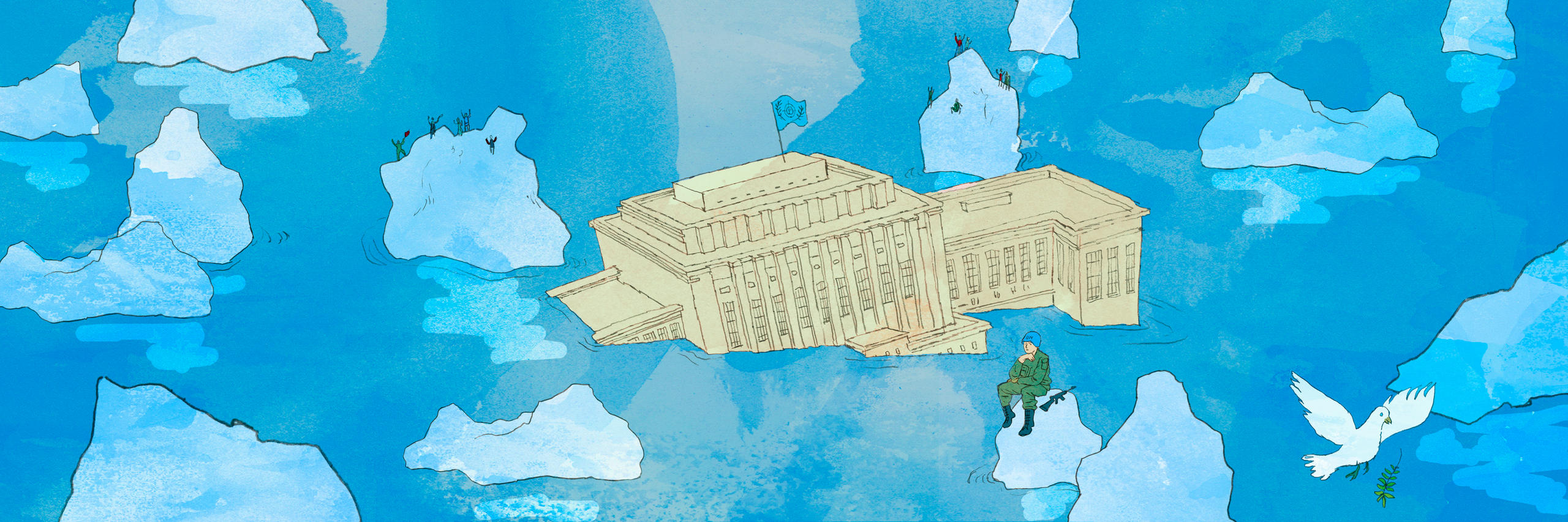

Does the UN have a future?

Each year in December, the United Nations Emergency Relief Coordinator makes a pilgrimage to Geneva, to unveil the UN’s humanitarian appeal for the upcoming year. The idea is to outline the areas the UN thinks will need help, what sort of help, and how much. As you can imagine, the figures are staggering: from Syria to Yemen, Afghanistan, Gaza, Lebanon, DRC, Ukraine, and more, 305 million people are estimated to be in need.

The UN is asking for $47 billion, to help not all, but around two thirds, or 190 million of them. Aid agencies won’t get as much money as this of course, they never get as much as they ask for. Almost certainly, as with this year, where food support in Syria, and clean water programmes in Yemen had to be but, some vulnerable people will get no help at all.

Journalists in Geneva are used to the UN pleading for cash, but this year was a little different. Tom Fletcher, just appointed to the role of Emergency Relief Coordinator, pointed to a challenge facing UN aid agencies that wasn’t about shortage of money.

‘It’s not just the ferocity of these conflicts, Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Syria’ he told us. ‘It’s about that wilful neglect of international humanitarian law.’

Record numbers of aid workers – protected under international law – were killed in 2024, Fletcher reminder us. ‘We seem to have lost our anchor somehow. That scaffolding, that we felt was there, international humanitarian law that I was hoping we’d be taking for granted at this point, is shaking.’

Dismantling of international law

His words struck a chord with me. For months now, UN diplomats in Geneva have been saying, at first quietly and off the record, but increasingly loudly, that the fundamental principles of international law, the Geneva Conventions, the ‘rules based order’, are under attack. The UN Human Rights chief, Volker Türk, warned in October that ‘the international rule of law is being progressively dismantled.’

This week’s Inside Geneva, our last podcast of 2024, asks whether that is really the case, what the consequences might be, and whether there is anyone left to stand up for that rules based order.

Richard Gowan, UN director at the International Crisis Group, sees a ‘turbulent few years’ ahead for the United Nations, and its efforts to find multilateral solutions to global challenges. Arguments over Gaza, or Ukraine, he told me, are ‘proving more and more toxic inside the security council.’

Other UN member states, he adds, are ‘watching this, they’re seeing a fragmenting international order, and they are profoundly frustrated.’ It will become harder and harder for them, he predicts, to persuade their own governments that the UN remains a worthwhile institution.

Where is the solidarity?

Meanwhile Jan Egeland, once UN Emergency Relief Coordinator himself, and now secretary general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, believes the last few years have seen declining commitment towards those in need.

Egeland was in charge of the UN response to the most devastating natural disaster the world has ever seen, the Asian tsunami of 2004. He remembers how quickly billions of dollars were raised. Now, he feels that solidarity, that belief in the collective good that the UN could bring, is lacking.

‘The ideals were shared by more governments, there was more unity of purpose’ he tells Inside Geneva. ‘And today there is more nationalism, introspection, skepticism. Europe first, America first, me first, rather than humanity first.’

More

Will the United Nations soon be obsolete?

Double standards

All our guests on Inside Geneva this week agreed that perceived double standards – particularly from the big powers – were proving, as Gowan put it, ‘toxic’ for the multilateral system, and for unified support for international law.

Nico Krisch, professor of international law at Geneva’s Graduate Institute, highlighted the tendency of countries in Europe to approach international cooperation as a kind of pick and mix, from which they could select just the elements they liked.

‘If I see the Europeans talk about international law and the rules based order’ he told me, ‘but then keep supporting Israel in the face of the International Court of Justice, delivering weapons. Or not taking part in negotiations on the legally binding instrument on business and human rights that many countries in the global south want, then I ask well, what do you really mean by your commitment to international law and multilateralism?’

And over at the International Committee of the Red Cross – the guardian of the Geneva Conventions – chief legal officer Cordula Droege confessed she fears international law could be ‘unravelling’. Pointing to Lithuania’s decision to withdraw from the convention against cluster munitions, and rumours that others may leave the Ottawa convention against landmines, Droege warns of a ‘slippery slope.’

Of particular concern, she says, is the attempt by some warring parties to stretch the boundaries of what is permitted under the rules of war, by blurring the distinctions between civilians and fighters, or between hospitals and legitimate targets. Or, as Jan Egeland put it, ‘Now it seems OK to bomb hospitals because there might be a militant there somewhere. It’s not, it’s a war crime, and it has been for a hundred years.’

How to recommit

Is there a chance to revive commitment to multilateralism, and to international law? Richard Gowan suggests that although things are turbulent, the UN is still ‘doing good worldwide’. But he warns that the defence of multilateralism which Europe, led by France and Germany, launched in 2016, to counter a feared disengagement by Donald Trump, may not be forthcoming in Trump’s second term.

‘Now, if you’re sitting in any major European capital,’ he says,’ you’re not worrying about the future of the UN human rights council, you’re worrying about the future of NATO. And you have much less money than you used to.’

For those who view international law as something of a nuisance, especially when waging their own wars, Cordula Droege has some words of advice. First, she points out, obeying the rules of war isn’t just about being nice to civilians, ‘not targeting hospitals, not targeting schools, not targeting energy infrastructure,’ she explains, will mean that, when the conflict ends, as they always do, the reconstruction, and the cost of it, will be much less.

And if her appeal to bank balances doesn’t work, Droege has a more serious appeal, to the consciences, even the souls, of those fighting. It might be human to be so angry at your enemies that you can no longer see them as human, but, she warns, dehumanising others is hugely damaging for all concerned.

‘Humanitarian law is also based on the fact that to dehumanise your enemy means that you also dehumanise yourself’ Droege explains. ‘And if you do it on a large scale you dehumanise the entire society and the fabric of society.’

Our last discussion of the year on Inside Geneva is fascinating, and profound. Do listen, and let us know what you think – do the UN, or the Geneva Conventions, have a future?

More

Inside Geneva: Does the UN have a future?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.