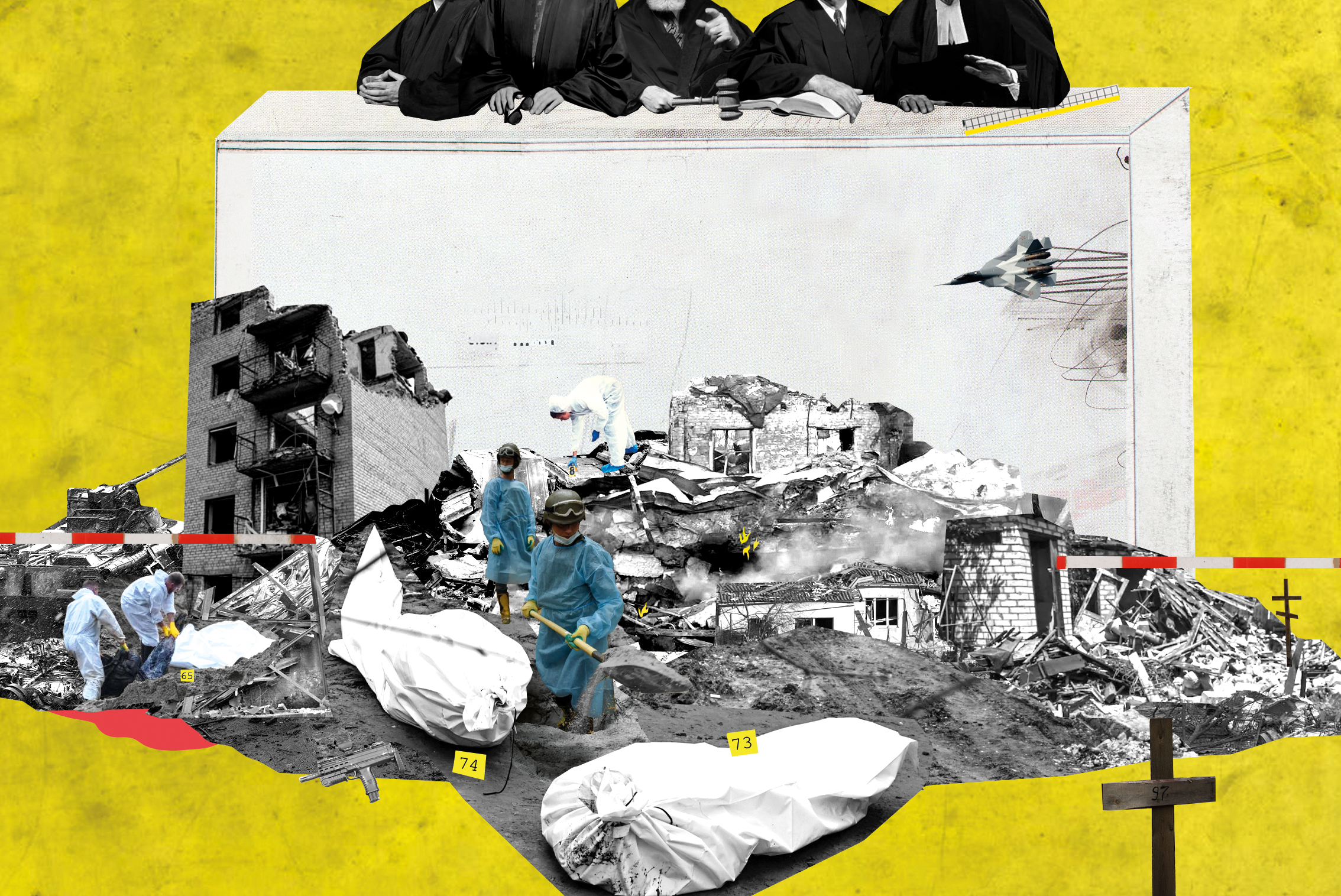

Lest we forget – why we need international law

Europe has been marking 80 years since D-Day. I doubt anyone reading this will have missed the solemn ceremonies in Normandy, the elderly men, all of them approaching, or already, a century old, who were part of that invasion.

For us, it’s hard to even contemplate what their experiences must have been. These were men, boys even, who waded through the waves and into machine fire with 80 pounds of kit on their backs. They watched their friends killed in front of them, and still kept going.

Bit by bit, the human lifespan is making our understanding of that part of history cloudy. The further each generation is from the Second World War, the more we tend to rely on fictional narratives of what it was like – Hollywood films, or Netflix dramas. And first-hand history isn’t only scarce because the generation who lived it is dying out – they also didn’t tell us much. The men in my family who served in the Second World War, like my great uncle, who was at El Alamein and Anzio, never talked about it.

More

Inside Geneva Podcast: is international law dead?

Why was that? Now, I wish I had asked him more. Then, I was a teenager interested in boys, music, and make-up. Not the memories of a kind but rather quiet old man. But I don’t think he would have told me what it was really like, even if I had asked him. I think that generation were resolved that what they went through, what they witnessed, had to be “never again.”

That’s why, in the immediate aftermath of that war, the world, including the big powers who were vying with each other for influence then just as they do now, united around some fundamental principles: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the Geneva Conventions in 1949.

These were the rules designed to make sure what happened in the Second World War, from the genocide of Auschwitz to the firebombing of Dresden, to the starving, in Nazi camps, of Soviet prisoners of war, must never happen again. Outlawing war was probably not realistic, but imposing some rules on its conduct, and on the way human beings treat each other in general, surely that was possible?

Law versus sovereignty

So how are we doing, 80 years later? We hear a lot about international law, especially here in Geneva. But today, when politicians refer to it, it’s often in terms that make it sound like a bit of a nuisance, and certainly not something that should get in the way of national sovereignty.

More

Geneva Conventions turn 75: are they still effective?

On Inside Geneva this week, we decided to be a bit provocative, and ask: “Is international law dead?” We recorded the episode in front of an audience at Geneva’s Graduate Institute, with expert input from international law professor Andrew Clapham, the ICRC’s head of arms and conduct of hostilities Laurent Gisel, and Cristina Figueira Shah, international law student and co-President of the Human Rights, Conflict and Peace Initiative.

Clapham began by telling us he believed we were at “a bit of a crossroads for international law,” pointing to perceived double standards over some countries’ response to the International Criminal Court (ICC) naming Vladimir Putin as a possible war criminal versus the reaction to the ICC’s chief prosecutor doing the same for Benjamin Netanyahu. “It’s quite blatant that when we like what the ICC is doing we will support it, but as soon as it steps out of line we will call it a ridiculous institution.”

Is there any way to dial down that politicised approach? Gisel pointed out that every country has ratified the 1949 Geneva Conventions – those laws are universal, and all countries are obliged to uphold them. But does that mean they do? Although the ICRC does not talk publicly about its conversations with governments, and the military, Gisel said he believes that dialogue, and the ICRC’s firm reminders of what the law says, have an effect “on a daily basis.”

Read more: Situation in Gaza ‘clearly a war crime’, says Swiss ICC lawyer

And, responding to questions about whether we are seeing more violations of international law, or whether they are just more widely discussed, Shah said she believes that “fifty or sixty years ago we as a society would not discuss those types of human rights violations in the same way…Now we have the law, and at least my generation or younger generations tolerate much less those types of violations, and we are reporting more.”

Our audience at the Graduate Institute provided some healthy scepticism. What evidence is there, asked one member, that international law has reined in any of the conflicts of the last decades, from former Yugoslavia, to Chechnya, Iraq, Ukraine, or the Middle East?

More

The dangers of a pick and mix approach to international law

Clapham provided a couple of examples: the 1997 Ottawa treaty against landmines has been so successful, he told us, that even non-state actors, armed groups, are not using them so much. There is evidence too that the forced recruitment of child soldiers is declining, even by the most brutal of militias.

And Gisel offered an example many of us were not familiar with: blinding lasers, weapons that were on the drawing board in the 1980s, were banned before they could ever be mass produced and used.

So, is international law dead? Our three panellists offered a clear “No…but.” To find out more, and to hear some ideas on how to revive those standards we set ourselves after the Second World War, you’ll have to listen to Inside Geneva, wherever you get your podcasts.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.