Can the WTO live up to its mission?

Global trade tensions are on the rise since US President Donald Trump took office. The Geneva-based World Trade Organization (WTO) was designed to keep trade relations smooth. How much can it do?

US President Donald Trump is delivering on his campaign promise and deploying sweeping tariffs to pressure neighbouring nations, transatlantic allies and rivals. Canada, Mexico, the EU and China are scrambling to respond.

China has announced retaliatory tariffs on several American agricultural products. Meanwhile Canada has imposed tariffs on a series of US goods including orange juice, peanut butter and coffee. The EU is mulling how best to respond to Trump’s threat of 25% tariffs on European goods.

On February 1, Trump ordered 25% tariffs on goods from Mexico and Canada, as well as 10% tariffs on imports from China.

Mexico and Canada benefited from a one-month pause to tariffs after agreeing to boost border controls.

US tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico took effectExternal link on March 4.

On March 3, the US imposed an additional 10% tariffs on all Chinese goods.

Tariffs of 25% on aluminium and steel imports are to come into effect on March 12.

Trump has also threatened 25% tariffs on European goods.

Last updated on March 11, 2025.

Retaliatory measures sell politically, some analysts note, but economically they come at a cost to all parties and tit-for-tats pave the way to trade war. Trump has admitted the US economy could know a “period of transition” as global stock markets slump.

The Geneva-based WTO was established under US and European leadership in 1995 to keep global trade smooth and provide an arena to settle economic spats. It replaced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). With trade tensions between major world economies running high, this could be its moment to shine and deliver on that mission.

“The WTO was created precisely to manage times like these – to provide a space for dialogue, prevent conflicts from spiralling, and support an open, predictable trading environment,” WTO director general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala recently reminded members gathered in Geneva.

The question is: can it? Not likely, say experts.

“Trump couldn’t care less about whatever rules there have been in the WTO,” says Cédric Dupont, professor at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Geneva. “For him, it’s transactional. It’s bilateral. And he doesn’t really want to bother with the WTO.”

Former Swiss Ambassador to the WTO Didier Chambovey agrees. “The US is acting as if it were not a WTO member in terms of tariffs,” he says. Chambovey was also head of the body responsible for arbitrating complaints at the organisation.

WTO membership implies a series of privileges and obligations. The lynchpin is access to global markets under fair and predictable conditions: members enjoy the privilege of non-discriminatory trade. Obligations include reducing tariffs, avoiding quotas, and facilitating smooth trade through efficient custom procedures.

Tariffs are taxes governments impose on imported goods and services, rendering foreign products more expensive than domestically produced alternatives.

When a country imposes a tariff such as a 25% duty on imported steel, the importer must pay that percentage to the government before selling the product domestically.

These customs duties can be used to protect domestic industries from foreign competition, raise government revenue, or address trade imbalances. Tariffs can also be used for diplomatic leverage.

The Trump administration sees trade deficits in a negative light. It has turned to tariffs to reduce them in the name of protecting US industry and to achieve goals as disparate as controlling migration to stopping the flow of Fentanyl, a drug which kills hundreds of thousands annually. The risk is that tit-for-tat measures escalate to full-blown trade war sweeping multiple countries and economic sectors.

There is little the WTO can do to push the US to play by the rules of international trade. The WTO is member-driven and has no agency to act on its own, notes Dupont. Most WTO member states, for now, are in wait-and-see mode when it comes to Trump’s agenda, which shifts day-to-day. Washington is clearly no fan of the WTO and has already ignored some of its past rulings.

Paradigm shift

US policy, note the ambassador and the professor, has led to the weakening of the WTO since the era of President Barack Obama. The first Trump administration de facto killed the WTO’s appellate body, which functions as the top court of global trade, by blocking appointments of new members to replace those retiring.

Facing a barrage of trade disputes at the WTO over policies similar in spirit to those coming into play now, including global tariffs on steel and a tariff war with China, the US argued the appellate body had overstepped its authority by reversing the decisions of expert panels.

US President Joe Biden did not change course and further weakened the organisation. His administration notably ignored a ruling that found Trump’s 2018 steel and aluminium tariffs violated the United States’ WTO obligations.

The change in the US approach, in the ambassador’s assessment, reflects a “paradigm shift”. When China joined the WTO in 2001, the expectation from China was reform. Trade liberalisation was supposed to push it – and Russia, which joined just over a decade later – towards a market economy.

Instead, by the mid-2000s, China had leaned into various forms of state intervention: subsidies, cheap loans, and forced technological transfer. It gained an edge in industries such as electric vehicles, steel, and shipbuilding. Meanwhile, in the US and in the European Union manufacturing jobs shrank, fuelling political backlash.

A 2020 study by the Economic Policy Institute concluded that the growth of the US trade deficit with China between 2001 and 2018 was responsible for the loss of 3.7 million US jobs. Three-quarters of those jobs were in manufacturing. During the same period automation was also a big driver of job losses.

The WTO failed to curb what some in the EU and US considered to be China’s unfair practices, leaving Washington frustrated. When it brought cases to the WTO, it lost key disputes, for instance on what constitutes a public body versus a private entity – a thorny issue when it comes to interpreting WTO rules on subsidies and countermeasures.

“In some high-profile instances, the Chinese prevailed,” says Chambovey. “That’s how the discontent developed. It seems that the US concluded that the WTO is not the right way to address the issues they have with China.”

Beijing still turns to the WTO to raise its issues with the US. As soon as Trump slapped 10% tariffs on all Chinese goods exported to the US, it immediately filed a complaint at the WTO. It later responded with tariffs of 15% on some US agriculture imports including chicken and corn.

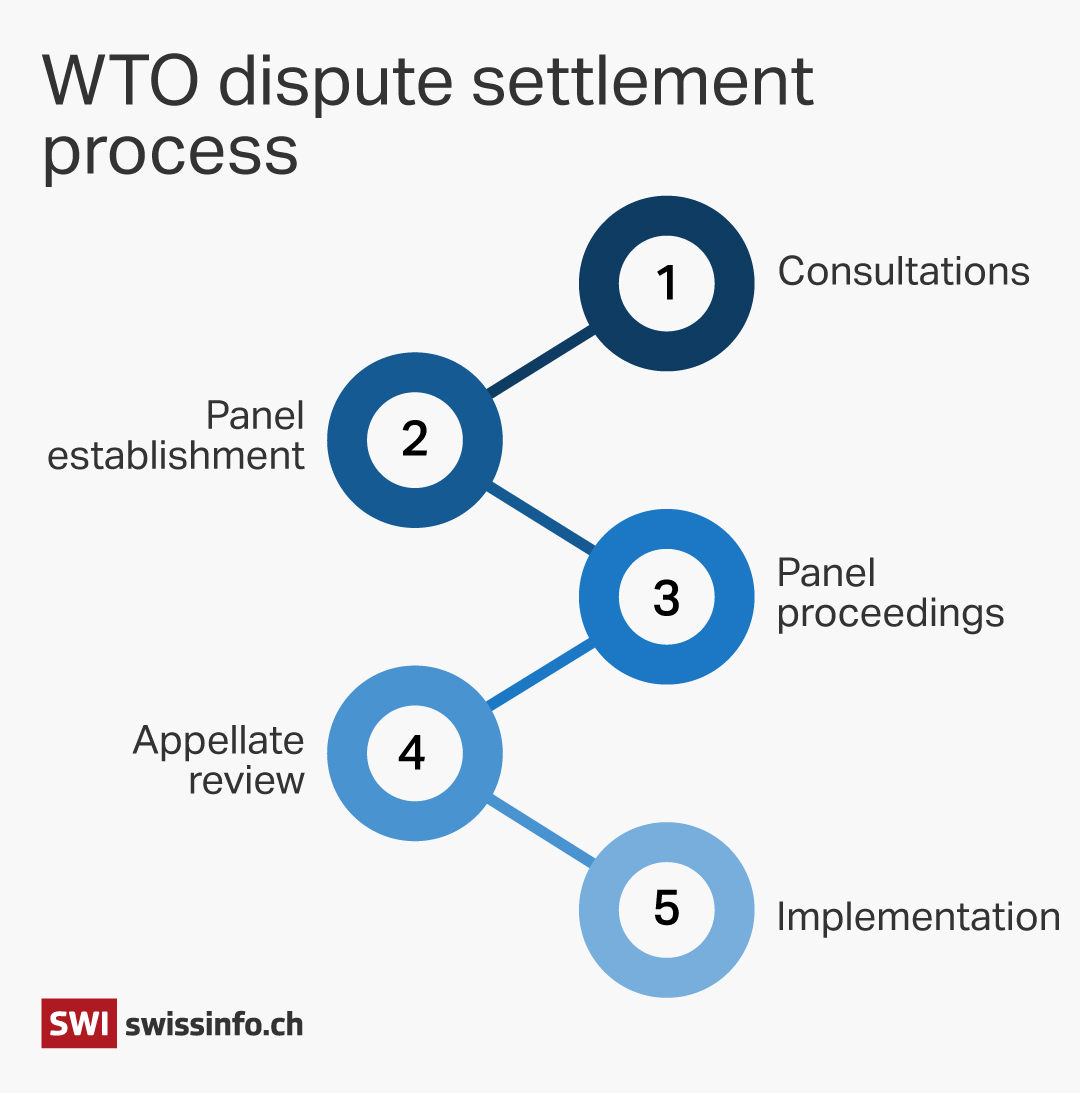

The WTO dispute process could lead to a ruling that Trump violated trade rules, as was the case in 2020, when the body found that his China tariffs broke trade rules.

But victory for China, which in principle would require Trump to recall his tariffs, would be primarily symbolic. The US could appeal, but that would go nowhere due to the WTO’s powerless appellate body. Nonetheless, Beijing appears to see some value in the process.

“The Chinese want to show the US that ‘we are the good guys, we are good multilateral players and you are the bad guys’,” says Dupont. “But it’s also because they do understand that this institution is useful. And if you no longer have that institution, what are you going to be left with? Bilateral all the time? That’s a pain.”

Alternative solutions

Nonetheless, the WTO is not obsolete. It has continued to help its members solve trade disputes, even in the absence of a functioning appellate body, although at a much more modest scale. Recent years have seen consultations on disputes ranging from intellectual property rights to the trade of agricultural goods and anti-dumping measures.

But without a functioning appellate body the WTO is currently powerless to make legally binding decisions. “It’s clear that the WTO is not in good shape,” says Chambovey.

A preference for plurilateral processes is also evident in the decision of other countries to create the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) in 2020 to bypass the statement at the appellate body. That provides a space for China and the EU to resolve problems with each other, even if not with the US. The decisions of the MPIA, unlike the appellate body, are not legally binding.

+ WTO members agree on temporary body to settle disputes

“If you cannot use the appellate body, no panel conclusion is going to have any bite because the US is not part of the MPIA,” notes Dupont.

The WTO – which has reached few multilateral agreements in its history and both experts concur needs reform – lacks the power to meaningfully play referee in conflicts involving the US. But still Dupont and Chambovey say it can be a relevant institution, even in the era of Trump.

“There is considerable trade interaction that doesn’t involve the US. And, so far, other countries are still interested in the WTO,” says Dupont. “It doesn’t mean the WTO cannot work. The US is playing a very dangerous game, because the world will organise more and more without the US.”

Chambovey agrees. “What the other WTO members should do is uphold the system – live up to their commitments and preserve what is left from the system,” he says. “The WTO will remain relevant if other members play by the rules.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

Picture research by Helen James and graphics by Kai Reusser

The story was updated on on March 18 to specify that US tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico took effectExternal link on March 4 and not March 1 as was previously stated. And to specify the title of Didier Chambovey.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.