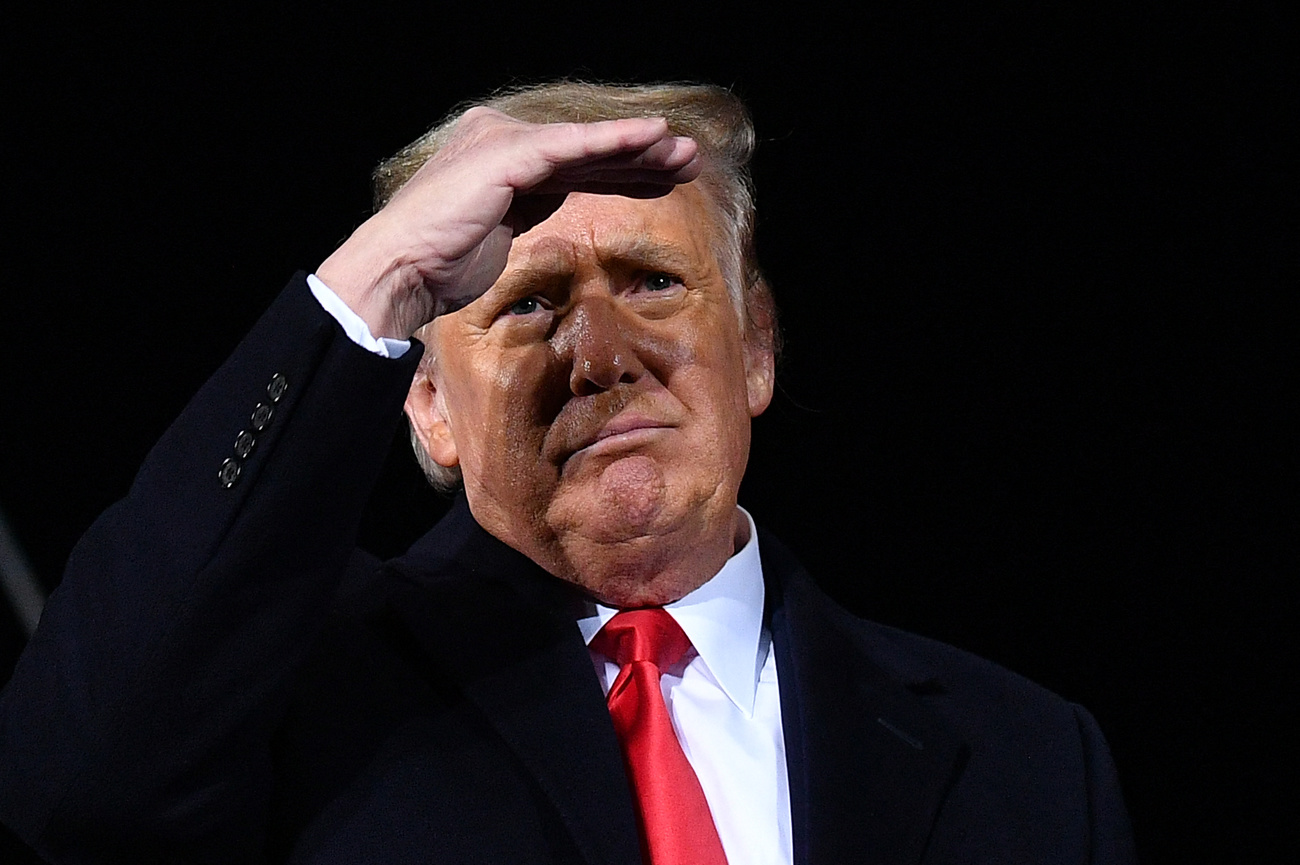

Trump, the UN, and the future

It’s fair to say it’s been a pretty turbulent few weeks for the humanitarian community in Geneva. First came the announcement that the United States would leave the World Health Organisation.

Then Israel’s ban on UNRWA, the United Nation’s agency for Palestinian refugees, came into force. And finally, in what one analyst described as a “shock and awe” moment, the Trump administration announced it would freeze funding for foreign aid.

In this week’s Inside Geneva, we take a deep dive into the implications of all three of those decisions – what they mean for humanitarian work worldwide, and what they tell us about the UN’s relations with the US, and even the future of the UN itself.

More

Inside Geneva: Trump and the UN

Our guests are Lawrence Gostin, Professor of Global Health Law at Georgetown University in Washington DC, Joergen Jensehaugen of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo (PRIO), who has written a report on the impact of the UNRWA ban, and journalist Colum Lynch, longtime observer of the UN and US foreign policy for, among others, the Washington Post, Foreign Policy, and now Devex. (https://www.devex.com/External link)

While the US decision to leave the WHO was not unexpected – Trump tried to do the same thing in his first term but ran out of time – Lawrence Gostin is nevertheless “angry and disheartened”. As someone with decades of experience in public health, who has worked closely with the WHO, he can see only disadvantages in the US strategy.

“This is going to mean that all of the vital work of the World Health Organization – polio eradication, AIDS, TB (turberculosis) and malaria – all of this important work is going to be even more underfunded,” Gostin told Inside Geneva.

Bad for the US too

Gostin stresses that leaving the WHO cannot be good for the US either. Citing emerging pathogens, Ebola, or the avian flu currently circulating in north America he says, “it makes us isolated, alone, and far more vulnerable and fragile against all kinds of health threats.”

The head of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has appealed to member states to try to persuade Trump to change his mind. That may be wishful thinking; the flurry of executive orders coming from the White House, some of them legally questionable, suggest this administration is keen to get on with things, whatever the cost.

Gostin, who, like his longtime colleague and former US chief medical advisor, Anthony Fauci, admits that he now fears for his personal safety because of his outspoken opposition to Trump’s public health policy, it’s now a matter of waiting and hoping for a change.

UNRWA ban challenges UN

The ban on UNRWA, like leaving the WHO, was not unexpected. Israel’s parliament approved it back in October, but ordered a 90 day interim period before it came into force. The problem, says Jensehaugen of PRIO, is that exactly how this ban should be implemented has never been made clear.

In East Jerusalem, UNRWA has closed its offices. In Gaza and the West Bank, Israeli officials are prohibited from having any contact with UNRWA. Since Israel controls these territories, and in particular what goes in and out of them, that, on paper at least, means UNRWA cannot operate at all.

The implications for aid distribution, in particular for northern Gaza, where thousands of people are now returning, in mid winter, to destroyed homes, are serious, says Jensehaugen. “UNRWA is what we call the backbone of the humanitarian operation. They don’t only bring in aid themselves, they are really the operation which all other humanitarian actors depend on.”

Surely then, it might have been better for the UN to use those 90 days to ramp up other agencies to replace UNRWA? In fact, with one voice, those agencies have said this is not possible. But Jensehaugen also highlights the UN’s “Catch-22” dilemma: on the one hand its “principled position” is that it cannot ramp up because it “cannot accept the legality of the {Israeli banning} law. The expulsion of the UN agency is illegal.”

On the other, there is the “humanitarian imperative. And the UN apparatus really loses out either way,” Jensehaugen told Inside Geneva.

“If they go all in on the principled stance, they’re not adequately prepared on the humanitarian stance. If they go all in on the humanitarian stance, they’re undermining themselves in a principled sense.”

Aid cuts across the board

The idea of other agencies stepping in to replace UNRWA may now be academic, because the US, the biggest donor to most UN humanitarian agencies, has ordered a freeze on foreign aid. Even if others had wanted to fill the gap, they probably now have no funds to do so.

All sorts of programmes, from de-mining, to HIV prevention, have been stopped. Those working on them have been told to stay home. It is, says Lynch of Devex “a death sentence for many small NGOs who just don’t have the finances to sort of weather this.”

Tragically, it may also be a death sentence for thousands of the world’s most vulnerable, who needed malaria treatment, or the mines removed from their schools and farmland, or any of the many other things the aid agencies do.

So what is Trump’s game plan, and what does it mean for the UN? Lynch does not think Trump actively dislikes the United Nations – and he’s certainly not the first US president to want to cut it down to size. “I don’t think he has any sort of inherent hostility towards the UN,” Lynch tells Inside Geneva. “I don’t think he’s particularly ideological. I think if it’s useful for him, fine. If it’s not useful for him, he does whatever he wants.”

Multilateral or transactional?

Reassuring words? Not really. The UN is supposed to be a multilateral, not a transactional institution. But Trump’s new ambassador to the UN, Elise Stefanik, has already suggested Washington favours certain agencies – the WFP (World Food Program) or Unicef (United Nations Children Fund) – because they further US interests.

For Lynch, the changes to the humanitarian aid system could be profound. ‘‘This is really the end of foreign aid as we know it,” he suggests. “Somalia, a couple of years ago faced a major famine. The Americans stepped in and provided over $1,000,000,000. I don’t really see this administration responding to a coming crisis with a major outlay of cash in the way that we have done historically.”

Gostin, meanwhile, is preparing to weather the next four years, and hoping for better things to come. “After four years, I do believe there’ll be a new president…and America will once again get back to our position as an international leader and someone with high values. That’s my hope and my dream, but it’s also my expectation.”

But in Oslo, Jensehaugen is less optimistic. “I think there is increasing disrespect for what the UN stands for,” he warns. “Can the UN survive this kind of strain? I really hope so. But we’re into difficult times. I have absolutely no doubt about that. I hope the UN manages to pull through.”

As we said at the beginning “shock and awe.” Listen to the whole discussion on Inside Geneva.

vm

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.