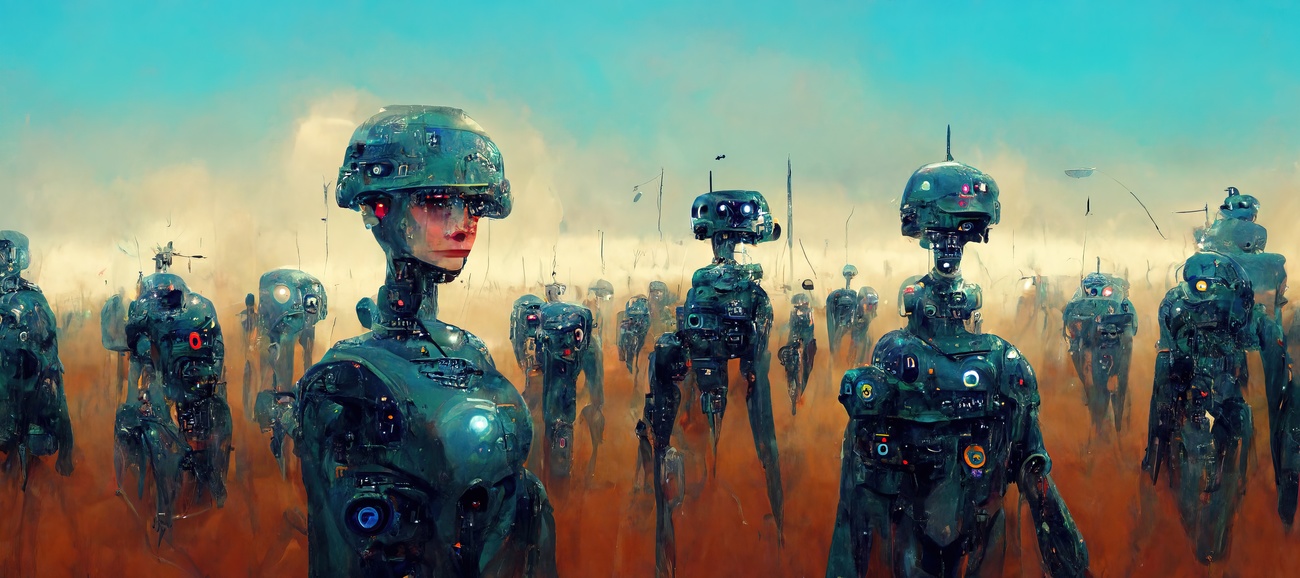

‘We have a unique opportunity to regulate autonomous weapons’

Killer robots are on the battlefield and humanitarian organisations are worried. Georgia Hinds, a legal adviser with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) stresses the urgent need for a binding treaty to prohibit and restrict autonomous weapons by 2026.

Inside Geneva Live Podcast Recording

We’d like to invite you to a live recording session of our Inside Geneva podcast about the role of the Geneva Conventions and international law. Mark your calendars – June 5, 2024, from 12:30 to 13:30 – at the Geneva Graduate Institute. Registration is required to secure your spot here.External link If you have any questions, please email us at event@swissinfo.ch.

Check out our selection of newsletters. Subscribe here.

According to a recent news report, artificial intelligence (AI) software known as “Lavender”, developed by the Israeli army, identified up to 37,000 potential targets in GazaExternal link. Israeli intelligence sourcesExternal link told reporters that the programme factored in an error margin of 10% and permission was granted to kill between 15 and 300 civilians as “collateral damage” per Hamas target, depending on their rank.

Israel is no exception. Throughout the world, war is evolving to become more digital, quick and automated, so much so that humans are left with only a few seconds to pull the trigger – or none at all. In Geneva, the United Nations and humanitarian organisations fear a surge in war crimes related to these technologies, which are evolving more quickly than their regulation.

More

New wars, new weapons, and lots of ethical questions

On the sidelines of the latest UN “AI for Good” conference, taking place in Geneva on May 30-31, SWI swissinfo.ch spoke to Georgia Hinds, a legal adviser for new technologies of warfare with the ICRC. Earlier this month, she published two new reportsExternal link on the impacts of AI on military decision-making and its implications for civilians, combatants and law.

SWI swissinfo.ch: What are the different kinds of military applications of artificial intelligence (AI) today?

Georgia Hinds: Artificial intelligence is being increasingly integrated on the battlefield in at least three key areas. The first is in cyber and information operations, changing the nature and spread of information, for instance with the use of ‘deepfake technology’ to fabricate highly realistic – yet fake – content. Another key application is in weapon systems, where AI is being employed to either partially or fully control functions such as target selection, or the launch of a strike, as is the case with autonomous weapon systems (AWS). Finally, AI is being used in tools to support or inform military decision-making, for instance by modelling the effects of a weapon, but also now to provide more complex recommendations about potential targets or courses of action.

SWI: With technology evolving so rapidly, can regulation keep up?

G.H.: We need to keep in mind that AI isn’t developing itself. Humans are choosing to develop this technology and they continue to have a choice about when and how to apply it on the battlefield.

International humanitarian law (IHL) does not explicitly regulate military AI or autonomous weapons. However, it is ‘technology-neutral’, meaning its rules apply to the use of any weapon or way of conducting warfare – so in that sense there is no regulatory gap. Human commanders remain responsible for ensuring that any attack respects the principles of distinction (targeting only combatants or military objectives), proportionality (avoiding disproportionate civilian harm) and precautions (taking all feasible measures to avoid civilian harm), whatever technology is used.

More

Swiss researchers warn about autonomous weapons

Having said this, for autonomous weapons in particular, we do see an urgent need for new, legally binding rules to provide further clarity and guidance as to how international humanitarian law applies to prohibit certain AWS and to constrain the use of others. This kind of guidance is needed not only for armies but also for industry, for developers, and also to address broader concerns that these weapons raise, including from humanitarian, ethical and security perspectives.

SWI: What measures should be taken to regulate autonomous weapon systems (AWS)?

G.H.: The ICRC defines autonomous weapons as systems that select and apply force to targets without human intervention. And we’ve called for a new, binding treaty, to be concluded by 2026, to prohibit certain autonomous weapons and to place strict constraints on the design and use of all others. In particular, these regulations need to prohibit unpredictable autonomous weapons (whose effects cannot be controlled, for instance when machines ‘learn’ on their own) and those that directly target people. These kinds of regulations are urgently needed to preserve human control over the use of force in armed conflict, and so to limit the effects of war and uphold key protections not only for civilians, but also for combatants.

SWI: In 2023, the UN Secretary-General and the ICRC President urged states to conclude a legally binding instrument to prohibit lethal autonomous weapons by 2026External link. Since then, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolutionExternal link that expresses concern about the risks of autonomous weapons. What are the next steps?

G.H.: In the coming months, the UN Secretary-General will produce a substantive report on autonomous weapons, based on the views of states, but also of international and regional organisations such as the ICRC, civil society, the scientific community and industry. It will then be up to the international community to act upon the recommendations of that report, and we are urging states to begin negotiations of a legally binding instrument, to make sure that key protections can be preserved for future generations.

More

Swiss army chief moots future purchase of armed drones

For over a decade, the different organisations in Geneva have been discussing the risks and challenges posed by autonomous weapons within the context of the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, which seeks to prohibit or restrict the use of weapons whose effects are considered excessively injurious or indiscriminate. We now have a clear majority of states in favour of legally binding rules and so we’re optimistic that this momentum can produce an effective treaty by 2026.

SWI: The “AI for Good” Summit is currently taking place in Geneva. Can artificial intelligence be used to avoid civilian harm during warfare and hence be more in compliance with humanitarian law?

G.H.: It’s important to critically examine any claim that new technologies will somehow make warfare more humane. We have heard similar claims before, for example in the context of chemical weapons and also drones, and yet we continue to see large-scale suffering and civilians being caught up in conflicts. Bringing more humanity to warfare requires prioritising compliance with international humanitarian law, with the specific objective of protecting civilians. We do recognise that there is potential for certain AI systems to assist decision-makers in complying with the law, for example in urban warfare if they can provide commanders with additional information on factors such as civilian infrastructure and population. At the same time, decision-makers need to understand and account for the limitations of these technologies, such as significant data gaps, bias and unpredictability.

SWI: According to an investigation by Jerusalem-based journalistsExternal link, the Israeli army has deployed a sophisticated AI system in Gaza to target presumed Hamas leaders. In some cases, the programme tolerates error margins of up to 100 civilian deaths per target, reports claim. What is your view on this? How can we hold countries accountable when no law exists?

G.H.: The ICRC is a neutral, impartial humanitarian organisation, and so we generally refrain from commenting publicly on specific uses and situations in ongoing conflicts – these are things that form part of our confidential, bilateral dialogue with the parties to those conflicts.

However, as I mentioned before, there is no lawless space or situation in armed conflict. International humanitarian law and the frameworks for accountability will continue to apply, no matter what tools are used. To apply these rules to an attack where a military had used an AI system, we could be looking into whether it was reasonable for a commander to rely upon the output of an AI system and whether they took all feasible precautions to avoid civilian harm.

SWI: Is humankind losing control over its weapons?

G.H.: The loss of human control over the effects of weapon systems is one of our key concerns in the context of autonomous weapon systems, particularly as we see trends towards increasingly complex systems, with expanding operating parameters. That being said, currently our assessment is that military forces continue to maintain remote piloting or oversight over weapon systems, even when certain weapons – such as armed drones – are advertised as having the ability to operate autonomously. It’s key now to set clear limits on the design and use of autonomous weapons, to make sure that this control over the use of force is preserved.

SWI: Robot soldiers could make up a quarter External linkof the British army by 2030. In your view, what does the future of warfare look like?

G.H.: Sadly, whatever technology is being used, the future of warfare looks horrible. That reality is sometimes lost when talking about new technologies, as these discussions happen far from the battlefield, and new technologies are somehow portrayed as clean or clinical.

More specifically, our reading is that physical robotic technologies are progressing more slowly than AI developments. The less visible advancements in AI pose immediate concerns, and these will no doubt eventually enable further robotic systems.

In the near term, we do see AI integration being a key feature on the battlefield, not only in weapon systems but throughout the planning and decision-making cycle, from providing recommendations to controlling aspects of weapon systems during attacks. Future warfare will therefore become increasingly complex and unpredictable. Therefore, our priority is to focus the international community’s attention on the specific applications of AI in armed conflict that pose the highest risk for peoples’ lives and dignity.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.