John Sutter, the Swiss slave-owner

In the 19th century, California proved to be a destination of choice for many Swiss. As far as the lucrative gold rush is concerned, the name of the German-speaking Swiss pioneer John Sutter, who gave his name to what is now Sutter County, California, goes down in history. This is the second of two articles on the controversial Sutter.

When Sutter founded the colony called Nueva Helvetia, he believed he would turn a profit from the cultivation of crops, livestock raising, production of spirits and handiwork. He was under pressure due to the debts he owed for services provided by rich ranchers and that had to be paid back. But Sutter also needed workers to provide for the running of the colony. To do this, he got involved in the enslavement of native peoples in the region, and even in the slave trade.

More

John Sutter: a Swiss with a dark side in the Wild West

He managed to create a private army of 200 men, mainly composed of native soldiers. He seized native populations from neighbouring settlements. The enslaved women and children were handed over for the most part to his creditors. The remaining men and women were subjected to a complex system of exploitation that ranged from contractual relations to forced labour. According to information provided by his overseer, Heinrich Lienhard, Sutter sexually abused indigenous women in his power. All of these crimes went unpunished, despite the fact that the brutal subjection of the native population violated a clause of the treaty ceding the lands in 1840, which called for the inhabitants to be treated with respect.

Between 1846 and 1848, during a war between the US and Mexico, the American expeditionary force under John Fremont took over the fort and forced Sutter to cooperate. He was then made a lieutenant of volunteers, appointed by the US government to maintain order on his lands. In fact California in 1847 was already controlled in large part by the Americans, and there was a great instability of institutions.

The discovery of gold on his lands in 1848 led to the notorious gold rush, which brought masses of prospectors from all regions of the US. These newcomers took over a large part of Sutter’s landholdings. By then Sutter was deeply in debt. But the value of the remaining lands in his colony grew as a result of the gold rush. In October 1848, Sutter decided to transfer the ownership of Nueva Helvetia to his son John A. SutterExternal link. In an area near the fort, his son planned the city of Sacramento, parcelled out the land, and with the proceeds of sale paid off his father’s debts.

In the meantime, Sutter the elder dedicated himself to agriculture and in particular to wine growing on his property, named Hock Farm, situated 60 miles north, on the banks of the Feather River. His was a large-scale agricultural operation involving crops, livestock, fruits and vines. The area was later named Sutter County.

Yet Sutter lost most of his fortune to partners involved in fraudulent schemes, and the prevailing anarchy frustrated his efforts to get back possession of his colony. The restoration of the rule of law after California officially joined the US in 1850 propulsed him into legal battles in defence of his land – fights that went on until his death. At the same time he occupied various offices, including delegate to the Constitutional Convention of the State of California. He unsuccessfully ran for governor in 1849, and became major-general of the California militia in 1853. Following the destruction of his headquarters due to arson in 1865, he moved to Washington, D.C., hoping to be compensated by the federal government. California awarded him a pension from 1865 to 1875. In 1871 he settled in Lititz, Pennsylvania, where he died and was buried in 1880.

Shattered myth

In his lifetime – but also in more recent times – the figure of “General Sutter” inspired adventure stories whose content was highly exaggerated. They were accepted in Switzerland without much critical evaluation. There were, in particular, totally unrealistic ideas about his wealth.

Martin Birmann, who acted as guardian of Sutter’s wife, laid the foundations of this myth with his book General Johann August Suter, published in 1868. But he was not the only one to exploit the theme. In 1925 there followed the novel L’Or: La Merveilleuse Histoire du Général Johann August Suter by the famous poet Blaise Cendrars, who was the first to give him the status of a hero. Following that, Stefan Zweig, Cäsar von Arx, Traugott Meyer, Helen Liebendörfer (as late as 2016!) and other authors wrote fictional accounts of his life. There was even a film made in 1936 by Luis Trenker.

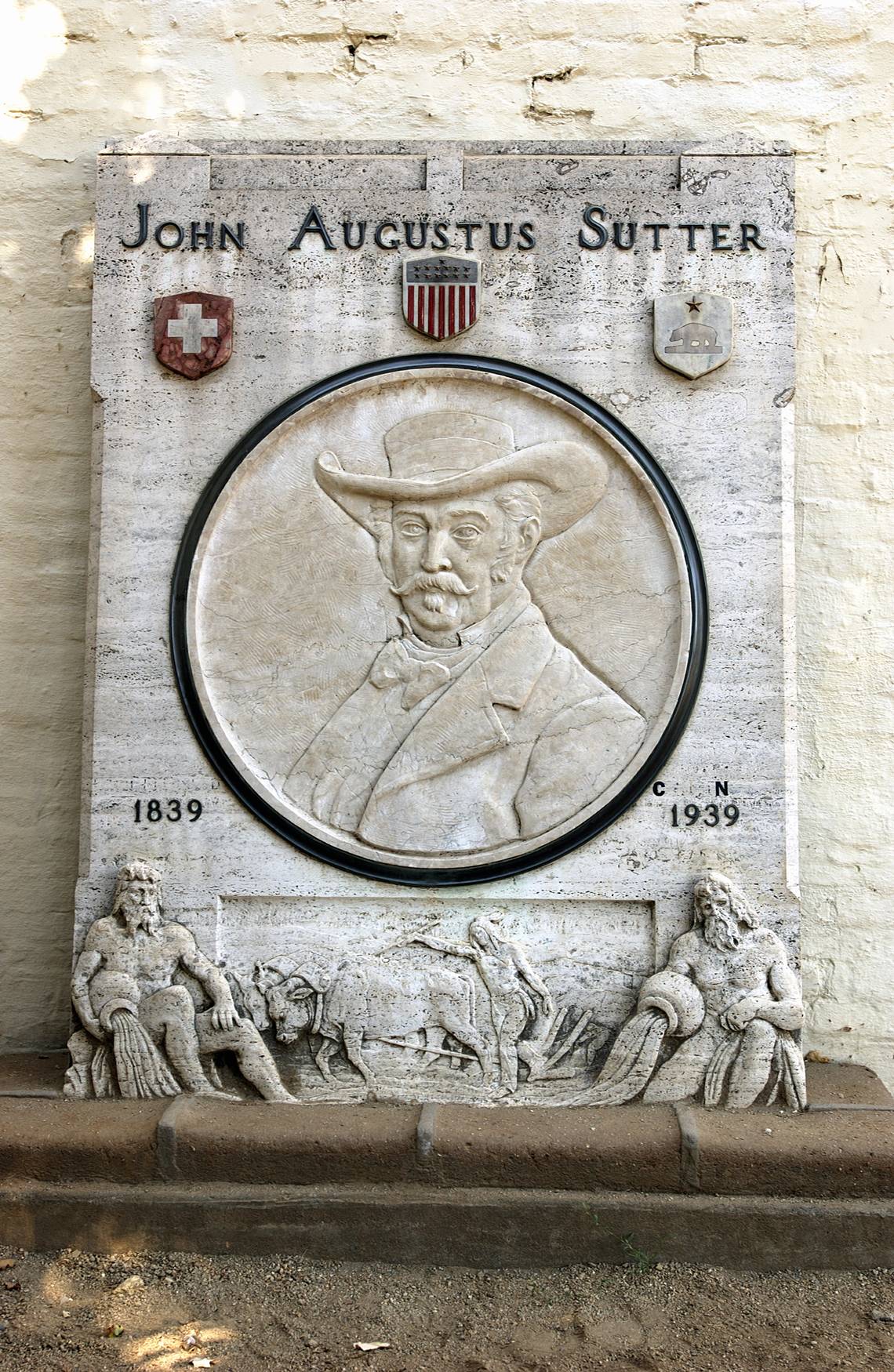

The exhibition Swiss in American Life, organised by Swiss consulates and partly funded by Pro Helvetia, the Swiss arts foundation, toured the US between 1977 and 1983. In it, Sutter was represented as a “great Swiss historical figure”. Finally, during the preparations for twinning the town of Liestal with Sacramento in 1989, the government of canton Basel-Land paid for a monument of Sutter to be erected in Sacramento, out of the cantonal lottery fund.

Beginning in the 1980s, new research in the US looked into aspects of Sutter’s career that had been glossed over in previous narratives. This research paid attention to the Native American perspective, giving greater visibility to the victims of the conquest of the American West. One author working in this field, Andrés Reséndez, coined the term “the other slavery”, referring to the subjection of Native Americans. So the romanticised picture of General Sutter has been overshadowed by the brutality of the historical person. According to Benjamin Madley, the inhuman practices of the system of forced labour introduced by the ranchers and Sutter himself only encouraged the violence shown by white Americans when dealing with indigenous tribes. It led to the genocidal atrocities that took place in California with the start of the Gold Rush in 1848.

As part of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, the simplistic view of John Sutter established in collective memory was called into question both in Switzerland and in the US. In Rünenberg, his Swiss birthplace, demonstrators draped his statue in a bloody banner, while in California his statue in front of the Sutter Medical Center in downtown Sacramento was taken down. Sutter remains a divisive figure, whose only justification could be the historical period in which he lived. He was a typical 19th-century robber baron, part of a society that experienced tumultuous social conflicts, colonialism and injustices of all kinds.

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.