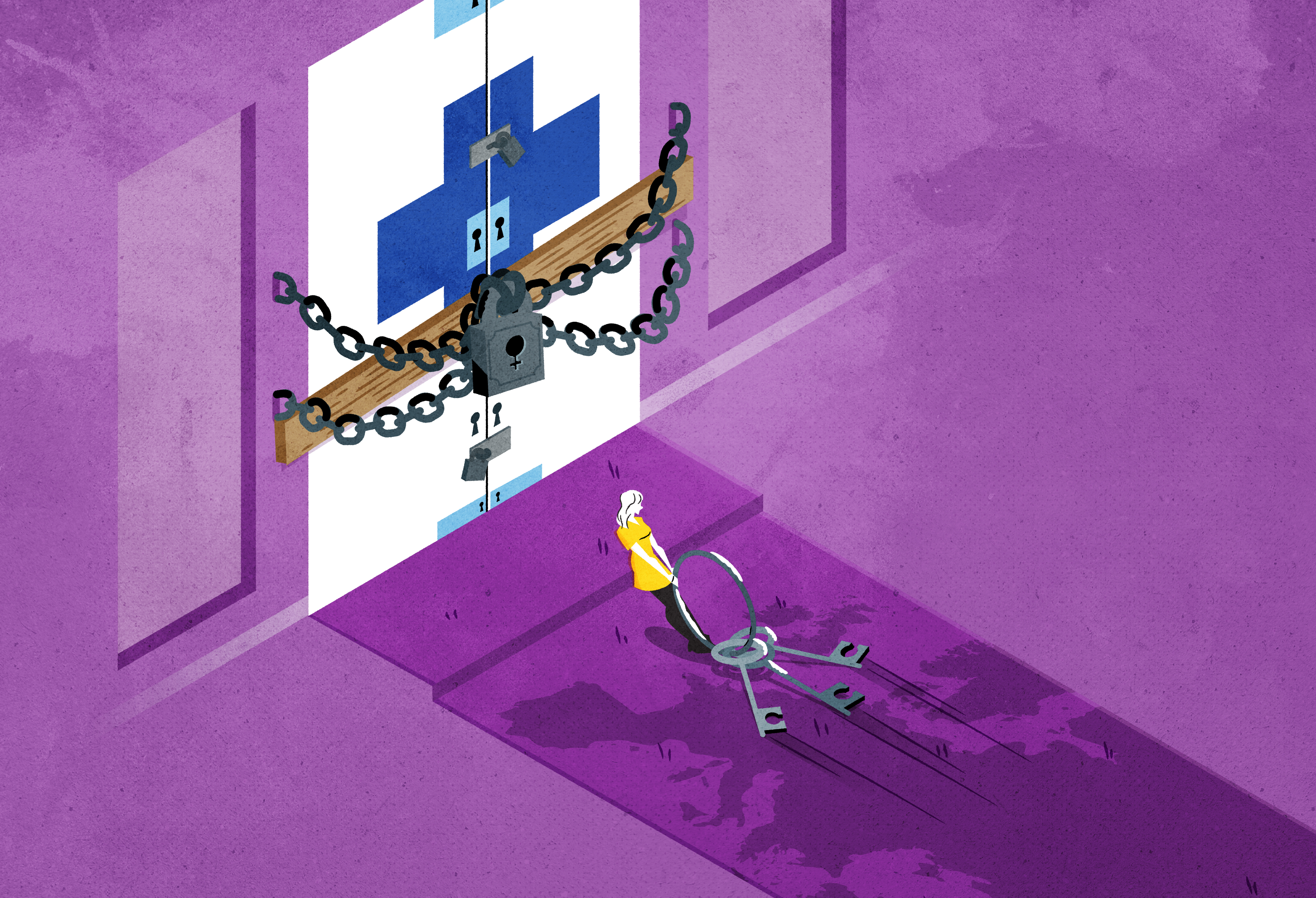

Abortion in Europe: a right for some, a fight for millions of others

Reproductive rights have been at the centre of political debates worldwide in recent months. As US President Donald Trump takes office following a campaign where access to abortion was a central theme, Europe too finds itself at a crossroads between liberal policies and restrictive laws.

As pro-life movements gain traction across the globe, campaigners are seeking an EU-wide guarantee to safe abortion access. From Hungary to Italy, France, Switzerland and beyond, we look at abortion rights from A European PerspectiveExternal link.

“I wouldn’t have handled another pregnancy, mentally or physically. But the procedure was horrible,” recalls Hanna (not her real name), a 32-year-old Hungarian psychology graduate. When she decided to get an abortion in Budapest, in the summer of 2023, this mother of two had to attend two medical appointments designed to convince her to bring the pregnancy to term, Hanna says. Eventually, she managed to secure a surgical abortion just five days before the 12-week legal limit. Throughout the whole process, she had to listen to the heartbeat of the fetus twice and received a paper with its vital information and age. “It’s horrible… You don’t want to do it. It was mentally exhausting and added guilt to an already difficult decision,” she told A European Perspective.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s conservative government has gradually undermined reproductive rights over the years. Hanna’s experience was a consequence of a law passed in September 2022, obliging people seeking abortion to be confronted with “vital functions” of the fetus “in a clearly identifiable manner”. Though described as a recommendation rather than a strict legal requirement, the process often means that the woman must listen to the fetus’ heartbeat.

Jennifer, 28, from Győr in northwestern Hungary, opted for a medical abortion across the border, in Austria, at a cost of €500 (CHF470). She recalls the Austrian clinic as “full of patients, mostly from Hungary and Slovakia – a conveyor belt, but in a good way”. After a consultation, she was given her first dose of medication and advised to drive home safely.

“In Austria, there were no questions, no watching videos of babies, no listening to heart beats. No one questioned my decision or made me feel ashamed,” she says. “If you can afford it, I’d recommend going abroad for better care. The process was emotionally taxing, but it was a relief to be treated with respect and dignity. It made all the difference.”

A tale of two realities

These stories underscore the divide within Europe on reproductive rights. While some countries pursue progressive legislation, others enforce some of the strictest conservative policies worldwide. In March 2024, France became the first country in the world to explicitly enshrine the right to abortion in its constitution, making it a European leader in assuring access to abortion.

Similarly, Slovenia provides a compelling example of free access to abortion. Though the right to abortion isn’t explicitly mentioned in its constitution, its Article 55 has enshrined freedom of choice in childbearing since Slovenia’s independence in 1991. Nowadays, the country boasts one of the lowest adolescent abortion rates in EuropeExternal link. “Slovenia’s example shows how normalising abortion access and integrating comprehensive education leads to better outcomes,” says Slovenian activist Nika Kovač, coordinator of the European ‘My Voice, My Choice’ campaign. “When abortion is legalised and accessible, the rates of abortions statistically decline because of better reproductive education,” Kovač explains.

In stark contrast, Malta entirely banned the procedure until 2023, even when a woman’s life was at risk. A recent legal change kept it highly restrictive, excluding factors such as rape or fetal abnormality. In this predominantly Catholic country, where Roman Catholicism is the state religion, deep opposition to abortion persists, with nine out of ten citizens opposing legalisation, RTBFExternal link reports. Upon joining the European Union in 2004, Malta ensured its national abortion law remained unaffected by EU treaties.

The Catholic Church’s influence can help explain Malta’s stance on reproductive rights. In his 2025 address to the Diplomatic Corps, Pope Francis called the notion of a right to abortion “unacceptable”, stating it “contradicts human rights, particularly the right to life”, Vatican NewsExternal link reports. According to the pope, “all life must be protected, every moment of it, from conception to natural death, because no child is a mistake or is guilty of existing, just as no elderly or sick person can be deprived of hope and discarded”.

“In the 49 countries across the European region, 44 have made abortion legal, based on request or socioeconomic backgrounds,” explains Leah Hoctor, the Regional Director for Europe for the Geneva-based Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR). Interviewed by RTS and SWI swissinfo.ch for A European Perspective, she identifies Malta as one of five exceptions in Europe including Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco and Poland “where abortion is basically not available”.

’20 million women do not have access to safe and accessible abortion in Europe’

Termination of pregnancy has not been permitted on request or for socioeconomic reasons since the 1990s in Poland. In October 2020, a ruling by the Constitutional Tribunal further tightened restrictions, banning abortion even in the case of fetal impairment. This decision effectively imposed a near-total ban, leaving countless women without legal options for abortion.

To help women navigate these constraints, activists established Ciocia Czesia (Auntie Czech), an initiative enabling them to travel to the Czech Republic for the procedure. Interviewed by Česká Televize for A European Perspective, co-founder Jolanta Nowaczyk comments: “In later stages of pregnancy, travelling abroad for an abortion may be the only feasible choice. For example, people usually discover that the fetus is malformed around 15 or 16 weeks of gestation, which is slightly too late for taking the pills. In such cases, they typically travel to countries like the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, or the UK.” However, travelling isn’t possible for all. Forty-four-year-old Magdalena, from Toruń, recalls: “I had my first abortion at the age of 24, using medications I found in a newspaper advertisement. They were sold as ‘restoring menstruation’. I had five abortions in total, and always did them at home, alone, using pills I bought online. Travelling abroad was never an option for me, I couldn’t afford it financially.”

“Only women who have the money to travel to another place can get leave [from work] and can pay for the hotel and the procedure, can do this safely and quickly,” comments Nika Kovač of ‘My Voice, My Choice’ campaign. This initiative seeks to ensure that all women in the EU have free access to safe abortion services, no matter where they live. “The situation in Europe is much worse than we thought,” says Kovač about the campaign’s research into abortion access. “Twenty million women do not have access to safe and accessible abortion.” Legalising abortion at the EU level is not an option, as abortion laws remain a sovereign matter for member states under EU treaties. Instead, the petition aims for policies enabling cross-border access for women in countries with restrictive laws. In December 2024, the ‘My voice, my choice’ campaign achieved one million signatures gathered in support of its proposed EU-wide abortion law.

In Brussels, RTBF met Lana Cop, one of the coordinators of the campaign, for A European Perspective:

Systemic barriers

“Even in countries with legal access, systemic barriers often prevent women from obtaining timely care,” says Leah Hoctor from the CRR. This includes places like France: in a survey published in September 2024, 82% of women who had had an abortion in the country said that obstacles remain, citing long waiting times and discrepancies in access between urban and rural areas, Radio France reportsExternal link.

In some countries, where there are legal rights to a safe procedure, the difficulty of finding a provider can lead women to seek abortion far from home. This is the case in Portugal. According to a recent reportExternal link by the General Inspection of Health Activities, many doctors in the country claim to be conscientious objectors, forcing health institutions to redirect patients.

This situation has driven many women in Portugal to seek abortion services abroad. In 2023 alone, 530 women living in Portugal had an abortion in the border clinics of Vigo and Badajoz in Spain, the national coordinator of the ‘My Voice My Choice’ campaign Diana Pinto, told Lusa.External link Yet in Spain too, gaps exist: between 2011 and 2020, 45,000 Spanish women had to travel outside their province for an abortion, RTVEExternal link reported in 2022.

On January 10, 2025, the Portuguese parliament debated amendment proposals to the abortion law in a session initiated by the Socialist Party (PS). Among other changes, the PS sought to extend the legal time frame to get an abortion. Ultimately, all proposed amendments were rejected – an outcome warmly welcomed by the Permanent Council of the Portuguese Bishops’ Conference, LusaExternal link reports.

In Italy, although abortion has been legal since 1978, the prevalence of conscientious objectors in the country – 90% in some regions – often forces women to rely on private healthcare or pro-choice groups. This was the case for Kiara, who lives in the province of Brescia, in the Lombardy region. Kiara found out she was pregnant in March 2022. “My plan to abort started immediately because I have no intention of becoming a mother,” she tells A European Perspective. “But when I went to my general practitioner, I found out that he was a conscientious objector.” She then turned to social media where she found the Telegram group “IVG Sto benissimo”, an Italian pro-choice network which puts women in touch with nearby medical providers who are not ‘conscientious objectors’. Similarly, Greta, 34, from Florence in Tuscany, says that as soon as she found out she was pregnant in 2019, her practitioner claimed he could not issue the certificate confirming pregnancy, the first step in getting an abortion. Greta had to go to a private gynaecologist. “This left me pretty bitter; no one should have to go to a private gynaecologist just to get a certificate,” she says.

For the TV programme “RebusExternal link” in 2021, public broadcaster Rai 3 met one of these conscientious objectors, Dr Maria Rosa D’Anna, director of the Pediatric Department at the Fatebenefratelli Hospital in Palermo. “I created a clinic that offers support to all the patients that come in and manifest a difficulty in carrying the pregnancy to term,” she said. “We suggest an alternative, which is to keep the pregnancy, offering this free-access clinic so to make their choice more aware.” Expressing her respect for Italy’s Law 194, which legalised abortion, she added “but it can’t be used as a contraceptive method.”

Italy’s far right government, led by Giorgia Meloni’s party Fratelli d’Italia, has faced repeated accusations of undermining women’s reproductive rights and supporting pro-life campaigns. On April 23, 2024, the Italian Senate gave its final approval to an amendment proposed by Fratelli d’Italia, legitimising the presence of anti-abortion associations in family planning clinics. In some hospitals, pro-life associations even have dedicated rooms in the same corridors where abortions are performed.

Cecilia Cardella, 78, is a volunteer for the Centro di Aiuto alla Vita (CAV, “Centre to help life”) based in Pisa, a branch of the Italian pro-life organisation Movimento per la Vita. “I’ve always had the idea of helping, rather than the mothers, children, including those at a very early age.” she tells A European Perspective. In Tuscany, barred from operating in local clinics by regional policy, the CAV relies on word of mouth and the support of doctors that are close to its vision, Cecilia explains. To women in need, it provides financial help – €200 per month for 18 months – as well as grocery packs and other essentials, aiming to incite them to bring the pregnancy to term. “When they come to us, if they’ve already made an appointment to terminate the pregnancy, we insist as much as possible on the other possibilities we can offer, to see if we can save that small life, which is so precious to us.”

In other regions, pro-life movements are already receiving institutional support in Italy. In 2022, the Piedmont regional councillor Maurizio Marrone, member of Fratelli d’Italia, allocated €460,000 to associations promoting “the social value of motherhood” and protecting “nascent life”. This amount doubled in 2023 and 2024. Laura Onofri, president of the association ‘Se Non Ora Quando? Torino,’ against gender discrimination, noted that only pro-life groups answered the call for proposalsExternal link: “there’s a clear desire to pressure women against abortion,” she says.

Criminal code and practice on papayas

In its guidelinesExternal link to enhance abortion care globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the procedure be decriminalised completely. Yet several European countries still have abortion clauses in their criminal code. Leah Hoctor from the CRR comments: “Two examples of this would be the UK and Germany. These are two countries where women can access abortion when they need it in general. But because of how it is treated in the criminal code, there’s still a lot of stigma around it. In the UK, we have seen a rise in prosecutions of women who have sought and have obtained abortion outside of the law. That is obviously a big concern for us”.

Termination of pregnancy is still officially a criminal offence in Germany as well. “Criminal laws create a chilling effect,” Hoctor adds. “Doctors may hesitate to provide legal services, and women face undue stress and stigma.” In October 2024, a coalition of 22 organisations urged the Bundestag to pass legislation that removes abortion from the criminal code, extending access to the procedure, from 12 to 22 weeks of pregnancy.

The legal status of abortion in Germany has led to a lack of medical training for doctors in this area. “Medical providers are not educated in the procedure as part of their normal course of study,” highlights Hoctor. This gap has led advocacy groups to organise “papaya workshops”, where professionals practise abortion techniques using papayas to simulate the process, as BR reported in May 2024.

In Switzerland, in 2002, voters approved legalising the procedure during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy “on written request by the woman, who must confirm that she is in a state of distress”. This requirement, and the fact that abortion laws are still governed by the criminal code, creates a persistent stigma, according to Barbara Berger, the director of Santé Sexuelle Suisse (Swiss Sexual Health). “This kind of system puts a lot of pressure on medical personnel, who want to be sure that a woman makes a good decision. This leads to moralising,” she said in an interview with SWI swissinfo.ch in 2023. Santé Sexuelle Suisse feels the solution is obvious: abortion should no longer be regulated by the criminal code in Switzerland, but instead by public health legislation, as in France. Berger believes this would allow the patient to make her own choice, allowing her to prioritise her health. “Once a woman has made her decision,” she said, “abortion should be available to her without delay and without obstacles.”

Historic shifts

Despite challenges in many parts of Europe, the landscape is shifting in some countries with historically restrictive stances on abortion. In 2018 in Ireland a referendum led to the repeal of the Eighth Amendment, which had recognised the “equal right to life” of the mother and the fetus. This change allowed the Irish parliament to legislate on the termination of pregnancy, resulting in the legalisation of abortions up to 12 weeks of pregnancy or later under certain circumstances. Pro-life movements remain active in the country, continuing to challenge aspects of the current legislation and advocate for further restrictions.

Meanwhile, in 2023, Finland passedExternal link a groundbreaking reform allowing women to terminate a pregnancy up to 12 weeks without justifying their request. Until this reform, Finland had the strictest abortion laws in the Nordic region, requiring approval from two doctors to proceed with a termination. While facilitating access and reducing stigma around abortions, the change of law did not significantly affect the number of procedures, according to statistics from the Finnish Institute for Health and WelfareExternal link. The path towards this historic parliamentary vote began with a citizen-led initiative called Oma Tahto (“Own will”), compelling lawmakers to address public demand for greater autonomy.

_________________________

Although not all were quoted, 11 women shared their personal stories for this report. Special thanks to all of them.

*A European Perspective is an editorial collaboration connecting European Public Service Media. Find out more hereExternal link.

Reporting by Martin Sterba (CT), Catherine Tonero and Garry Wantiez (RTBF), Rachel Barbara Häubi (SWI swissinfo.ch/RTS), Veronica DeVore (SWI swissinfo.ch), Sara Badilini (EBU), Alexiane Lerouge (EBU) and Lili Rutai (EBU).

Additional content provided by AFP (France), Arte (France-Germany), BR (Germany), Franceinfo (France), RTBF (Belgium), RTE (Ireland), RTP (Portugal), RTVE (Spain) and SWI swissinfo.ch (Switzerland).

Sub-editor: Kate de Pury (EBU)

Translation and edition for SWI swissinfo.ch: Veronica DeVore

Project Management: Veronica DeVore (SWI swissinfo.ch) and Alexiane Lerouge (EBU)

Illustration: Ann-Sophie De Steur

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.