Swiss mountain moved 10cm a year before crashing down

The mountain that sent four million cubic metres of rock through a Swiss village on Wednesday was known to be unstable. A section of the mountain moved 30 centimetres over the course of three years, but it was impossible to determine when it would collapse.

Several hikers are still missing in canton Graubünden after the rockslide swept down from Piz Cengalo, through the Val Bonasca and onto the village of Bondo. There was another landslide on Friday afternoon. Nobody was reported hurt.

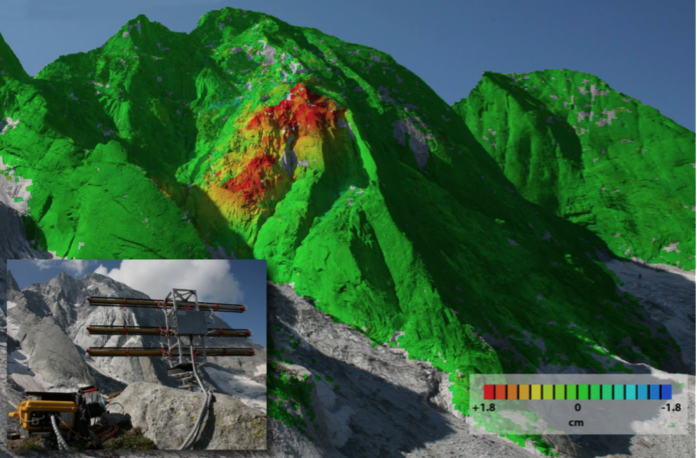

It followed a less devastating rockslide in 2011, which prompted researchers to take a closer look at the mountain between 2013 and 2016. Using radar and infrared technology, researchers found a large portion, of several million cubic metres (see pic), had deformed by 30cms over the observation time frame – 10cms per year.

The “Influence of Permafrost on Rockslides” report, conducted by ArgeAlp, stated the resulted indicated a “profound movement” of both “tilting and slipping”. The local authorities had already installed an alarm system to alert of any debris flows.

The problem was predicting rockslides with any degree of accuracy, explained Marcia Phillips from the SLF Institute for Snow and Avalanche ResearchExternal link in Davos. “Permafrost only has a small role to play in this size of event,” she told swissinfo.ch. “The geological structure of the mountain and water build up in its fractures were more important.”

Piz Cengalo is made up of layers of rock, “much like an onion”, she said. Water accumulated beneath the top layer, gradually pushing it out over thousands of years. “The cause of these events take place at depth and it can take a long time for the mountain to react,” said Phillips.

Ice recovered from fractures on another mountain was dated at 6,000 years old, she added. Given the deep-seated natures of the forces acting on the mountain, such large rockfalls could take place at any time of the year. Smaller events, governed by thawing permafrost, are most likely a few weeks after a heatwave.

WSL regularly monitors permafrost in the Swiss alps and bores holes in mountains to check the temperature of the rock. SLF checks areas from Piz Ketsch in Graubünden to the Matterhorn, Jungfrau and Klätsch in Glarus. But it does not bore on Piz Cengalo.

For several years, scientists have warned of a heightened risk of rockslides in Switzerland as rising temperatures thaw permafrost and melt glaciers. In the case of Piz Cengalo, the rockslide was caused by natural erosion forming fissures that allowed water to seep into the mountain. This effect is magnified when there are larger temperature differences between winter and summer, causing the water to turn to ice and then melt.

According to the Swiss National Platform for Natural HazardsExternal link, some 6-8% of Switzerland’s surface area is unstable. “Owing to the high intensity of certain mass movements, the technical feasibility of protective structures and other safety measures is often limited, or these may prove too expensive,” its website states. “As with other natural processes, the danger areas should where possible be avoided. Where this is not possible, very extensive measures may be required.”

More

‘Little chance of survival’ for missing landslide victims

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.