Lessons learnt ten years after Halifax crash

Chief air accident investigator Jean Overney was one of the first Swiss to arrive in Halifax on the morning after the 1998 Swissair crash.

He describes the crash of the MD-11 on September 3, 1998 – the worst in Switzerland’s aviation history – as an “exceptional air catastrophe, a unique case”.

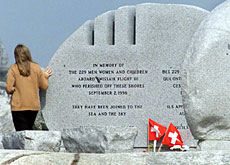

Overney had taken the reins at the Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau five months beforehand. On September 3, he received a call informing him of a Swissair crash over Halifax: flight SR111 from New York to Geneva had crashed into the sea and all 229 occupants were dead.

The experience he gained during the inquiry into the crash would later be useful for the engineer and pilot in managing other major disasters including the mid-air collision above Ueberlingen in 2002.

Overney left as head of the office in May this year, but continues to work part-time as a consultant to ensure a smooth transition to his successor.

swissinfo: How did you learn that Swissair flight SR111 had crashed?

Jean Overney: I was on holiday with my family around 60 kilometres from New York, near Boston, and a journalist from Radio Suisse Romande called me at the hotel. I had just started as head of the AAIO.

It was as if the world had collapsed around me. I jumped into a car, caught a Boston-Halifax flight reserved by Swissair and arrived on the scene at almost the same time as the Canadian investigators, who were quite surprised that I was already there.

swissinfo: What was your first task?

J.O.: A team of investigators had to be put in place. The bulk of the work consisted, in the first instance, of recovering the bodies. I went to Canada around 20 times overall. Two people from the bureau were assigned to the inquiry.

swissinfo: Did the collaboration with Swissair go well?

J.O.: We are not examining magistrates. Our role is to report on any malfunctions. Swissair and the SR Technics maintenance service worked together magnificently. They always supplied the necessary documents very quickly. SR Technics re-employed a former head who was retired at the time to lead the inquiry team and who knew the MD-11 perfectly.

swissinfo: What did this investigation bring you on a professional level?

J.O.: We learnt new techniques, for example about the repair of computer memory. And we learnt useful lessons in communication with the press. The Canadians had a very bad experience several years earlier and they learnt lessons from it. You have to be very open with the press. Likewise, there were no problems in working with the Canadian investigators, as is almost always the case in this type of situation.

swissinfo: And from a personal point of view?

J.O.: Let’s say first of all that one must separate the professional from the private. It was necessary to learn to control one’s emotions, to behave in an appropriate manner with the families. For example, we learnt that it was better not to bring too many people together at the same time. There had been some dreadful tragedies. I remember one mother whose son had a serious car accident and who had paid for his daughter’s ticket to return from New York to Switzerland.

But pain goes through several stages. At the start, the families always have hope. “There will be just one survivor and it will be my wife,” they think. Then comes anger, sometimes.

swissinfo: Anger against you?

J.O.: No, more against the company or the manufacturer. As the Swiss administration, our mission consisted of reassuring people who were clinging on to us. In these types of cases, we are a little like priests. We console, we listen. All requests must be taken seriously.

swissinfo: The inquiry did not uncover the cause of the disaster. Do you feel frustrated?

J.O.: We made an important discovery, that metallic PET films, that insulate electrics, resisted a Bunsen burner flame during tests but not a short circuit, as occurred in the SR111 flight. That allowed the certification rules to be adapted.

Of course, it would have been better still if one had found the origin of the short circuit. As a general rule, one does find the original cause of catastrophes. But in this case, the inquiry has certainly led to discoveries which mean that these 220 people did not die in vain.”

swissinfo-interview: Ariane Gigon

On September 3 at 0018 GMT, flight Swissair flight SR111 left New York for Geneva with 215 passengers and 14 crew on board.

The pilots noticed a suspicious smell 53 minutes later.

The pilots saw smoke and requested permission to land. They were redirected to Halifax. Communication with the plane ended six minutes before its impact with the Atlantic around Peggy’s Cove in Nova Scotia. The entire episode lasted 20 minutes.

The victims of the crash included 136 Americans, 41 Swiss and 30 French.

It took more than one year to recover 98 per cent of the debris.

The report by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada was published on March 27, 2003.

According to Swissair’s Geneva lawyer Christian Lüscher, the firm agreed to pay SFr198,000 ($178,360) for each victim.

One of the 155,000 electric wires was burned in two places.

Investigators decided this cable was probably where the fire started, above the cockpit.

A short circuit produced intense heat, which then set fire to the insulating material.

The investigation concluded that the fire started on the right of the cockpit, above the ceiling near the back. It then spread and severely damaged the control systems and the cockpit area so that the pilots lost control.

Among the 50 recommendations made afterwards by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada was that fire detectors should be compulsory in ceilings and in other places which cannot be seen.

Materials were made subject to new certification procedures.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.