Small ski resorts join forces to survive

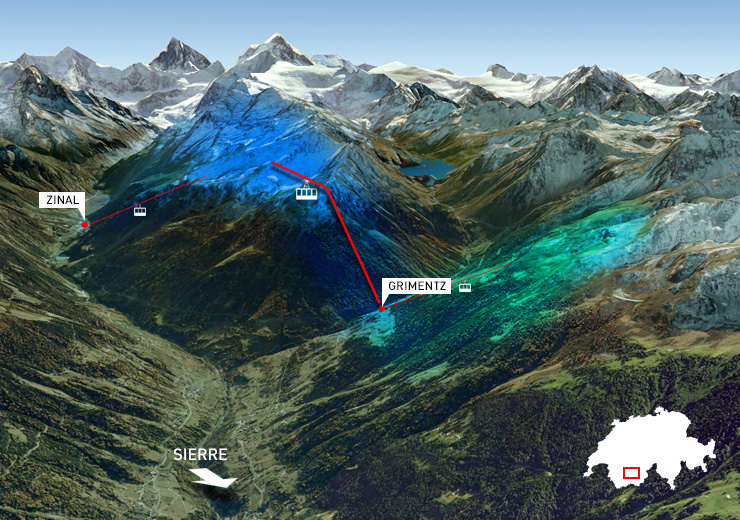

One large ski area is easier to market than two small ones. Grimentz and Zinal, in canton Valais, two resorts on a human scale, are now linked by cable car. But guaranteed snow and natural beauty may not be enough to ensure their future.

They are located in what geographers call a “hanging valley”. The road leading up to the Val d’Anniviers has first to negotiate an almost sheer rock face, twisting backwards and forwards round some 15 hairpin bends.

There is a clear view over to the northern side of the Rhone valley. The mountains over there are less stark. The terraced vineyards stretch right up to the plateau where Crans-Montana is located, a veritable town in the mountains.

It’s quite different on the Anniviers side. Here nature is untamed, with steep slopes, deep gorges, rushing streams and unspoiled villages.

Fifteen kilometres, 25 hairpin bends and eight minutes in a cable car later, you have climbed 2000 metres and find yourself at the foot of the Corne de Sorebois, one of the highest points of the Grimentz-Zinal ski area. There is an amazing view of the “imperial crown” as the circle of mountains is known: 30 peaks of more than 4,000 metres, including the famous Matterhorn.

“Pretty, isn’t it?” whispers Pascal Zufferey of the ski lift company that has been created as a result of the merger of the two areas. As of this winter, the new cable car makes it possible to access Zinal from the village of Grimentz. “We have linked two friendly little resorts, of comparable size but of different character: Grimentz tends to be family oriented, while Zinal is more for sports enthusiasts,” explains Zufferey, a native of the valley.

Snow conditions are ideal, even in this mild winter. That’s the benefit of a high altitude. In the Val d’Anniviers skiing starts above 2,500 metres and the top of the pistes lies almost at 3000. The ski areas start where those in some other resorts end – and some pretty famous ones too.

And to give nature a helping hand, there are snow cannons. “People have become very fussy,” explained Pascal Bourquin, head of the ski lifts. “They want faultless pistes, with not even the tiniest stone sticking out. We start making snow in the middle of November in order to have a good base layer that will last until Easter.” And there’s no problem about getting water for it: it comes straight from the huge Moiry reservoir.

From cows to sport enthusiasts

It’s coming to the end of the day at the foot of the pistes on the Zinal side. In its only shopping street the little resort has two trendy bars and a pub, on whose terrace a group of British tourists loudly discuss what they’ve done that day. What do they like about the place? “The snow, the scenery, the peace and quiet and the more or less guaranteed sunshine.”

Grimentz and Zinal are two villages at the end of the Val d’Anniviers, one of the side valleys in canton Valais leading from the southern ridge of the Alps down to the Rhone valley.

The southern ridge, which contains the highest peaks, is also the region with the greatest number of prestigious ski areas, which between them have hundreds of kilometres of pistes. They include the Portes du Soleil, most of whose resorts are in France (Champéry, Morgins, Avoriaz, Châtel), the 4 Valleys (Verbier, La Tzoumaz, Nendaz, Veysonnaz) and Zermatt.

The Val d’Anniviers has a second resort combining two villages, St-Luc/Chandolin, in addition to Grimentz/Zinal. In all, the valley has 220 km of pistes and 27 cable cars.

The resort of Vercorin, at the entrance to the Val d’Anniviers, is part of the commune of Chalais in the Rhone valley, and is not included in these figures.

Population

15 villages

2,600 residents (population)

750 hotel beds

1200 beds in group accommodation

20,000 beds in chalets and holiday flats

The population of the valley can therefore go up almost tenfold when the resorts are full.

Further on, a crowd of Belgians are enjoying a stroll round the village. They are staying at the Intersoc holiday club, which with 550 beds is the biggest hotel establishment in the valley. It took over the premises that used to belong to the Club Méditerranée.

In his restaurant, which now serves a range of sea food alongside its typical local dishes, Rémy Bonnard is well placed to observe the way the village has developed. His parents bought one of the first hotels in Zinal in 1944. At the time the plateau was simply used as a spring pasture for the cattle before they moved further up the mountain for the summer – what’s known as a mayen. Nobody lived there all year round. “They only installed heating in 1960, when the first ski lift opened,” Bonnard recalled.

Today there’s no need to go as far as Zinal in order to get to the pistes. Thanks to the new cable car, visitors can leave their cars in Grimentz, eight kilometres down the valley. So is Bonnard worried about losing customers, especially since half the skiers just come for the day?

“I’ve been doing business here for 35 years, and would have been tempted to say ‘yes’. But in fact, the real reason why we get fewer customers is that the permitted blood alcohol level is now lower, and enforcement is more rigorous. Before, people used to stay on until about ten in the evening in order to avoid getting stuck on the motorway. But now they go home as soon as they’ve taken off their skis.”

Construction ban

Go to the other village, and the feel is quite different. While Zinal extends into the meadows, Grimentz is built against the side of the mountain. Famous for the old chalets lining the main street, the heart of the village barely seems to have changed over the course of the last five centuries. Of course there has been a lot of construction further away from the centre, but all of it in chalet style. And nothing too big.

But there will be no more building. On March 12, 2012, Swiss voters approved the initiative launched by ecologist Franz Weber, which severely limits the construction of second homes. In canton Valais the impact has been brutal. It is impossible to get by without tourism here, and construction became the direct consequence.

“A disaster,” said Zinal architect Gabriel Vianin. “It’s not so bad for me, because I am 67. But what about young people who have taken over their parents’ businesses, and can only keep on four or five workers where before they had 20 or 30? What are they supposed to do with the others?”

The fact is that there will soon be no land left where construction is permitted. Simon Wiget, the young head of the Sierre-Anniviers tourist office, is only too well aware of the fact. But what really annoys him about this abrupt halt is “the feeling that we are seen as an Indian reservation that people want to keep as beautiful as possible in order to spend their holidays here, but where they wouldn’t dream of actually living, because they want all the conveniences of living in towns”.

The feeling is widely shared throughout the valley – even if nature-lover Zufferey predicts that “in 20 years from now, perhaps we’ll be thanking Franz Weber”.

But what’s to be done in the meantime? There’s a real lack of hotels in the Val d’Anniviers: 750 beds, against 20,000 in flats and holiday chalets.

“But if you aren’t an international chain, you have practically no chance of building a hotel,” warned local mayor, Simon Epiney. “No bank will lend you money. In the whole of canton Valais Zermatt is practically the only place where you have hotels that manage to survive in the mountains.”

Hara-kiri

CHF30 million ($34 million) is the cost of the new cable railway – the third longest in Switzerland – linking the ski areas of Grimentz and Zinal. The commune provided a loan of CHF12.5 million while the Confederation and canton Valais provided CHF8 million. The ski lift company RM Grimentz-Zinal (annual turnover: CHF15 million) found the remainder, mainly by increasing its capital.

CHF400 million is the total amount of investment made in 2013 by Remontées Mécaniques Suisses, the umbrella association of cable car companies. In addition to Grimentz-Zinal its other large project was the CHF50 million invested in the ski lift linking Arosa and Lenzerheide in canton Graubünden.

CHF757 million is the total turnover of Swiss cable cars for the season 2012-2013. It has been falling continuously since the 2008-2009 season, when it reached a high point of CHF862 million. Three quarters of Swiss cable car companies face financial difficulties.

(source: RM Grimentz-Zinal, Remontées mécaniques suisses)

“The hotel industry in the Alps as a whole really needs a makeover,” independent consultant Laurent Vanat, an expert in mountain tourism, told swissinfo.ch. “Especially if you compare it to Austria next door, where everything is nicer, newer and less expensive.”

“Switzerland is the only alpine country where every year 200,000 skiers go to a different alpine country to ski, mainly to Austria,” he pointed out.

“There’s a real imbalance in our competitiveness with Austria,” Epiney agreed. “The number of Swiss going to Austria has shot up incredibly in the last ten years. And you have to admit that visitors are often treated better there and the facilities are more modern and more attractive. The Austrians have made tourism into a major industry, with loans at almost zero interest rates. In comparison, Swiss help to tourism is just a joke.”

“This country is committing hara-kiri. It has forgotten that the advantage of tourism is that it can’t be relocated. Twenty years ago Switzerland was one of the five most popular destinations in the world. Today it stands somewhere between 20 and 30…”

What makes the outlook even worse is that specialists see young people losing interest in winter sports. In the 1980s snowboarders represented a new clientele for the resorts, but now numbers are falling off, and schools in Switzerland’s plateau area are having more and more difficulty in organising their traditional ski camps.

The possible disappearance of low altitude ski areas because of climate change isn’t good news for Valais either. “A large number of our customers are people who learned to ski in low altitude resorts. So we aren’t at all happy to see the resorts in cantons Fribourg, Jura and Vaud disappear, because that’s where our future clients first acquire their skills,” said Bourquin.

An island of light

However, people in the Val d’Anniviers don’t give up easily. And they are ready to help each other out. In 2006, 70% of them voted in favour of merging their communes. The schools in the valley were merged into a single centre, in Vissoie further down the valley, in the early 1970s.

Since then, cooperation in other areas has been successfully expanded: sewage, rubbish collection, tourism promotion, ski lifts.

“It wasn’t too difficult to organise all this. We know each other because we were all at school together,” said Wiget.

Night has fallen in Grimentz. In the midst of the dark chalets, the little ice rink seems to float like an island of light. Caught in the yellowish floodlights, two children are skating round on the natural ice. It’s as natural as the huge expanses of virgin snow, and as the face of the two little resorts struggling to survive in a battle of giants.

2012-2013 season

France

57.9 million skier-days (the number of skiers multiplied by the number of days skied)

Turnover of cable car companies: CHF1563 million

Austria

54.2 million skier-days

Turnover of cable car companies: CHF1492 million

Switzerland

25.4 million skier-days

Turnover of cable car companies: CHF757 million

(source: Laurent Vanat, consultant)

(translated from French by Julia Slater)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.