Switzerland’s housing shortage: how bad is it?

With high immigration and not enough new houses and flats being built, Switzerland’s housing shortage is getting worse. Just how severe is the problem, and what will drive the developments ahead?

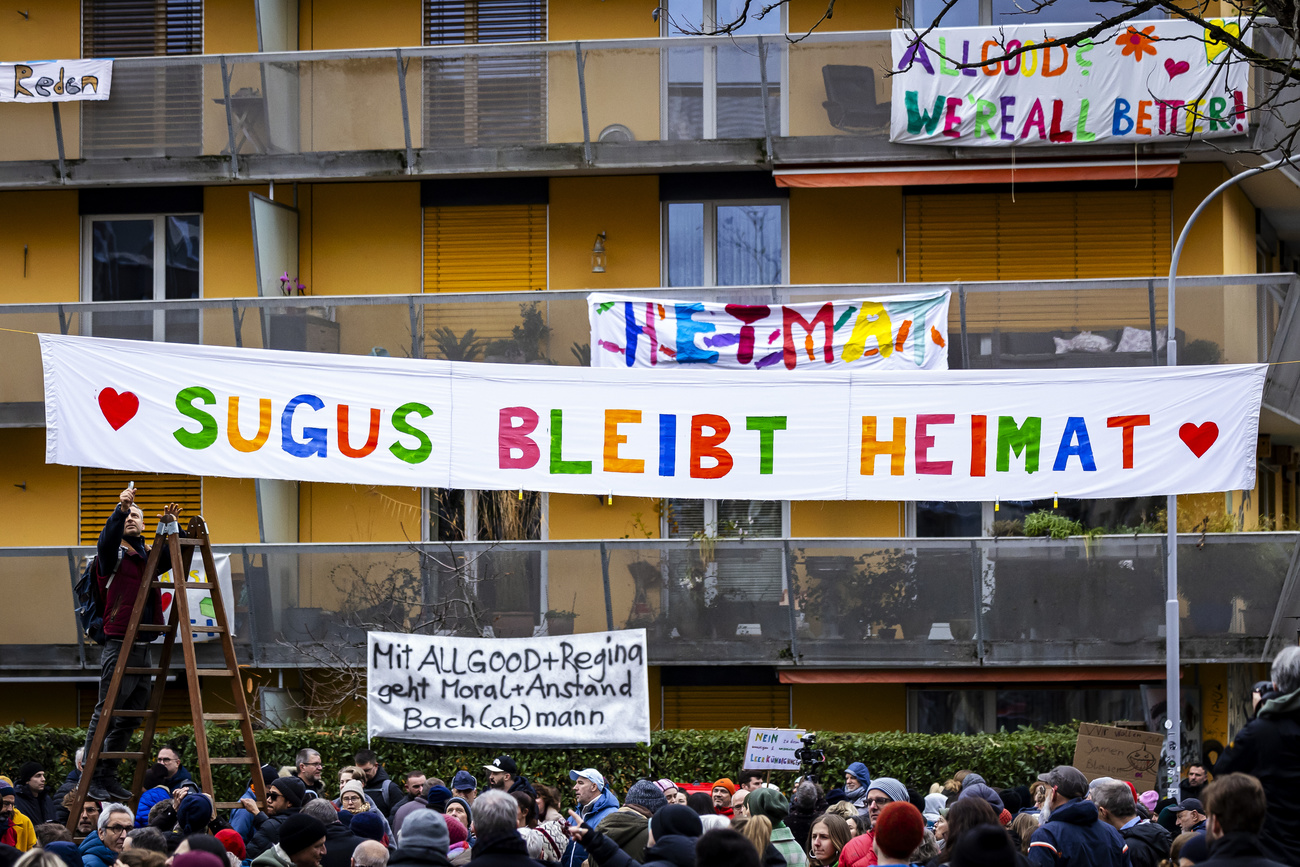

At the end of 2024, angry and desperate families joined demonstrations in Zurich over the so-called “Sugus buildings”. Around 100 tenants had been given eviction notices shortly before Christmas as the buildings required major renovations.

The owner, a wealthy heiress, refused to engage in talks, even with the Zurich authorities. Such housing protests, which drew nationwide attention, had not been seen in years.

The Sugus buildings have long since come to symbolise the wider failings of the Swiss housing market.

Finding a flat in Zurich is notoriously difficult. The local vacancy rate – the clearest indicator for housing availability – recently stood at 0.07%. This is the lowest not only in Switzerland, but probably in the entire Western world.

>>Read this special focus on the unprecedented housing crisis in Zurich.

More

Zurich: how the world capital of housing shortages is tackling the problem

But how much does Zurich’s story reflect the wider picture in Switzerland? What factors are driving the housing shortage – and where is it headed? We look at what leading experts and the data have to say.

Is there currently a housing shortage in Switzerland?

The short answer is yes and no. The most recent national vacancy rate in Switzerland was 1.08%. This means that, across the country, there is no acute housing shortage. But it is a tight market. According to the Federal Office for Housing, anything below 1% is defined as a housing shortage.

Compared with other countries, Switzerland lags. In a studyExternal link by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from two years ago, Switzerland joined Sweden at the bottom of the vacancy rankings.

The situation in Sweden has eased slightly, with the current share of available rental dwellings at 1.3%External link. Meanwhile, it has continued to deteriorate in Switzerland, where in all central locations, the proportion of available housing is well below 1%.

“With the exception of the very small countries, Switzerland currently has the lowest vacancy rate in Europe,” says Robert Weinert, chief analyst at the consulting firm Wüest Partner. But Switzerland is not the only place facing these issues. “Cities such as London, Paris and Munich are in the same situation. Too little housing is being built in urban areas across Europe.”

A new index from Wüest Partner, which compares the housing shortages in Europe using several criteria, ranks Switzerland fourth behind Luxembourg, Norway and Ireland.

And the outlook is far from encouraging. At the beginning of April, the Swiss Contractors’ Association issued a warningExternal link that only 42,000 new flats would be built in 2025, whereas 50,000 would be needed, according to the Federal Office for Housing. The result? The vacancy rate is set to dip below 1%.

What are the causes of the housing shortage?

Claudio Saputelli, head of property analysis at Swiss bank UBS, puts it simply: “The issue is not primarily one of supply – it’s demand.”

A period of higher capital interest rates, rising costs of building materials, and a shortage of skilled labour have all slowed down new construction projects in recent years. However, the main driver of the housing shortage is immigration.

In 2024 alone, Switzerland – a country of 9 million – gained around 83,000 more residents than it lostExternal link, most of them workers from the European Union. Over the past decade, the population has grown by an average of 0.9% per year – and new construction has not kept up.

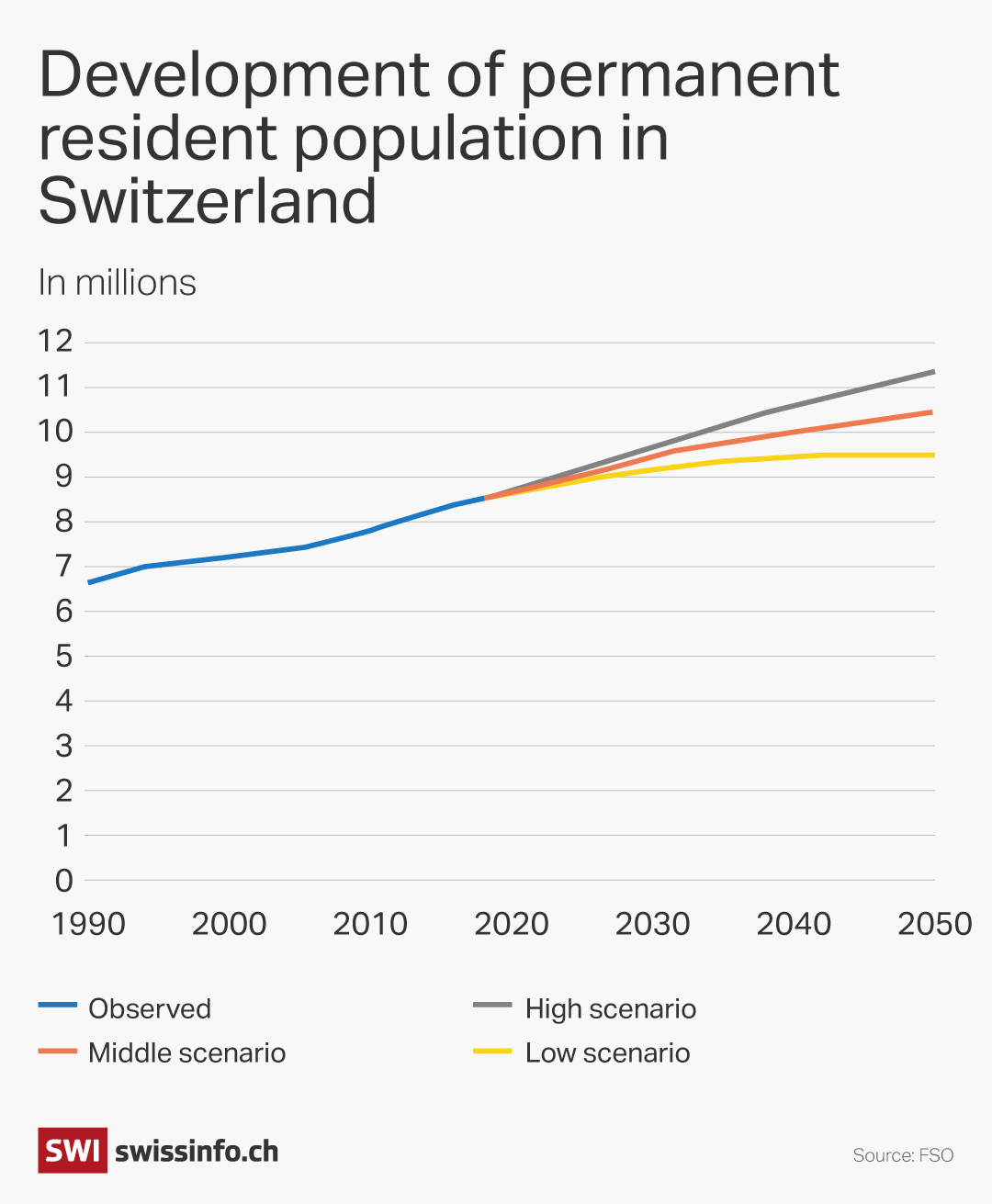

The Federal Statistical Office expects the population to reach 10 million by 2040, and 10.5 million by 2055. These figures reflect the medium-range “reference scenario” – one of three projections.

Although immigration has slowed slightly and the global economy is cooling due to disruptive forces, population growth in Switzerland is likely to continue.

How precarious is the housing shortage in historical terms?

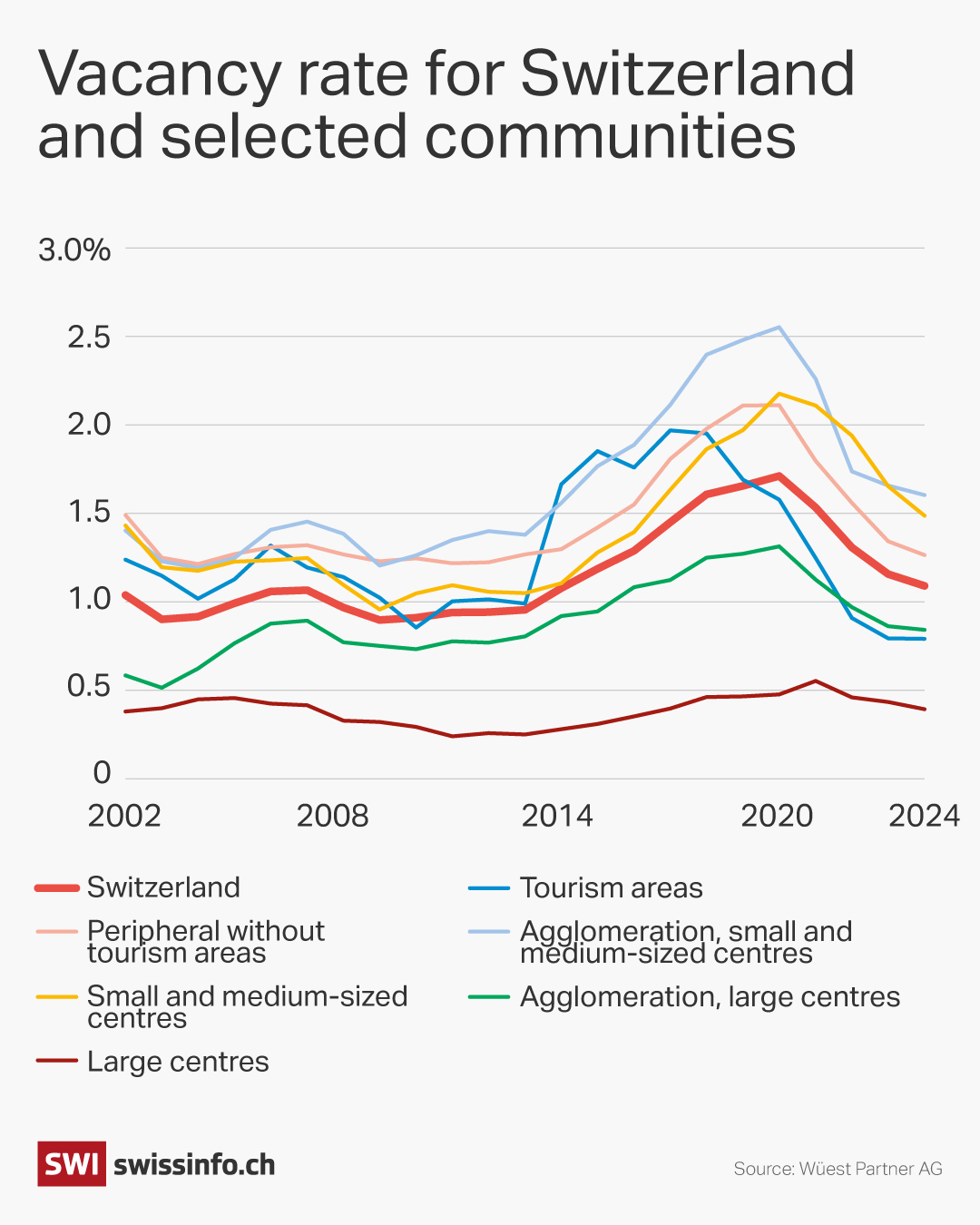

The situation today is not as dire as the headlines, protests and international comparisons might suggest. Switzerland is still feeling the effects of a housing market rebound at the end of the last decade when interest rates were low. At that time, following a period of intensive construction, more properties stood empty across the country.

“Before Covid, vacancy rates hit a record high,” says Saputelli. With the bond market offering little return, a lot of money flowed into new property development. “Back then we were complaining about too many empty flats – though only in the areas around urban centres, not in the cities themselves,” he says.

That period, when it was easier to find housing outside the centres than it is today and prices were falling regionally, appears now as a peak in the vacancy rate that has since collapsed. The surplus has been used up, and figures are now back to early-2000s levels.

A breakdown by type reveals a strikingly flat trend in the major urban centres. These areas never really saw a recovery.

The sharpest rise and fall in vacancy rates occurred in tourist areas, where demand for holiday properties surged during the pandemic. As a Tages-Anzeiger headline put itExternal link in early April: “Even the tourism director hasn’t found a flat.”

If you look further back, there have been far more extreme housing shortages in Switzerland. After the First and Second World Wars, and again in the 1970s and 1980s, urban housing became scarce and social tensions flared.

The Historical Dictionary of Switzerland notes that until 1992, supply “consistently lagged behind demand, and there was no reserve of empty flats to regulate the market”.

Even now, vacancy rates are well below the level needed for a balanced market with stable rental prices. A study by Wüest Partner puts the “ideal rate” for Switzerland at 1.27% – well above the current 1.08%. Since the figure depends on factors such as price levels and geographic location, it varies from canton to canton. Wüest Partner found the lowest ideal vacancy rate in Zug (0.44%) and the highest in Solothurn (2.36%).

What is holding back construction in Switzerland?

The major obstacle to new construction is the 2014 Spatial Planning Act, which permits almost no new zoning. As a result, land available for development is becoming increasingly scarce. The restriction is a deliberate political decision in a country which is densely populated.

The political response to the shortage of building zones is densification. Where green space no longer exists, building upwards is the answer. The idea enjoys broad political support, but implementation has proved difficult.

More

Swiss property prices rose almost 2% in 2024

According to the current building and zoning regulations, the city of Zurich could accommodate 650,000 residents in its urban area – about 200,000 more than today. But the potential for densification is not used, sometimes because of property owners’ personal reasons, but often because adding extra floors is not worth the investment.

Another factor that is typically Swiss is the influence of objection procedures. “Lodging an objection is the fifth national language,” says Ursina Kubli, head of real estate research at Zürcher Kantonalbank (ZKB), one of Switzerland’s largest banks.

Two years ago, ZKB conducted a study on the impact of densification on housing growth. It found that in canton Zurich this so-called “building on existing stock” had generated just over 1,400 new flats per year. This amounts to about 14% of new residential construction. In the city of Zurich, the study found that although there is significant potential for adding storeys, very little is actually being built.

Projects which entirely replace buildings have a much more significant impact. These are known as “new replacement buildings”. According to figures from the city of Zurich, demolition and reconstruction on the same site creates living space for 87% more people on average. Critically, it is these projects which are most targeted by legal challenges.

To address this, Switzerland needs to have a clear discussion about who can lodge an objection, where, and under what conditions, says Kubli. This view is widely held among property experts, and the Swiss Contractors’ Association has also called for appropriate action.

More

Wealthy Switzerland is a country of tenants

Could low interest rates turn things around?

There is a glimmer of hope in monetary policy. The low interest rates could give the construction sector in Switzerland a much-needed boost. In March, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) cut its benchmark rate for the fifth time in a row, to just 0.25%. More cuts are likely: according to the Bankers Association, more than half of experts expect Switzerland to return to zero or even negative interest rates this yearExternal link.

This would provide a strong stimulus for construction, as UBS analyst Saputelli explains. “It’s not a linear story. If interest rates fall from 1.5% to 1%, there is little effect. But negative interest rates really hurt. That is when many pension funds start looking for bond alternatives.” The recent turmoil on the financial markets could further amplify this effect.

But because construction takes time, any shift of investment into real estate will be felt with a delay. The housing shortage will remain an issue in Switzerland, says Wüest Partner’s Weinert. “At least for the next five years, which is about as far ahead as we can see.”

More

Edited by Balz Rigendinger/adapted from German by David Kelso Kaufher/sb

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.