Rare diseases take centre stage at global health summit

The needs of millions of people with rare diseases were finally recognised as a priority at the world’s largest global health meeting. Patients now hope this will nudge drugmakers and national health authorities to improve access to diagnosis and treatment.

Nearly 200 countries gathered at the World Health Assembly at the United Nations in Geneva last week to lay out a roadmap for the future of health. In a first, countries adopted a resolutionExternal link on Saturday calling for a “comprehensive action plan” on rare diseases. This diverse group of over 7,000 known illnesses include some of the more common rare diseases cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that affects the lungs, and sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder. While most of these diseases remain individually rare, they collectively affect over 300 million people in the world.

The resolution, which acknowledges rare diseases as a global public health priority for the first time, was welcomed by patients, their families, and health systems that have been complaining about delayed diagnosis, the prices of available therapies, and lack of awareness and social support.

“There wasn’t anything for rare diseases – no action plan, no global strategy,” Alexandra Heumber Perry, chief executive officer of the patient alliance Rare Diseases International (RDI) told SWI. “The resolution is a historic milestone.”

More

Pandemic treaty comes as welcome sign of multilateralism

The resolution urges World Health Organisation (WHO) member countries to develop national health plans for rare diseases, including policies to improve diagnosis, access to affordable treatment and more research and innovation. The resolutionExternal link also commits the WHO to put together a 10-year global action plan on rare diseases – which it defines as those affecting 1 in 2,000 people or fewer, about 7% of the world population.

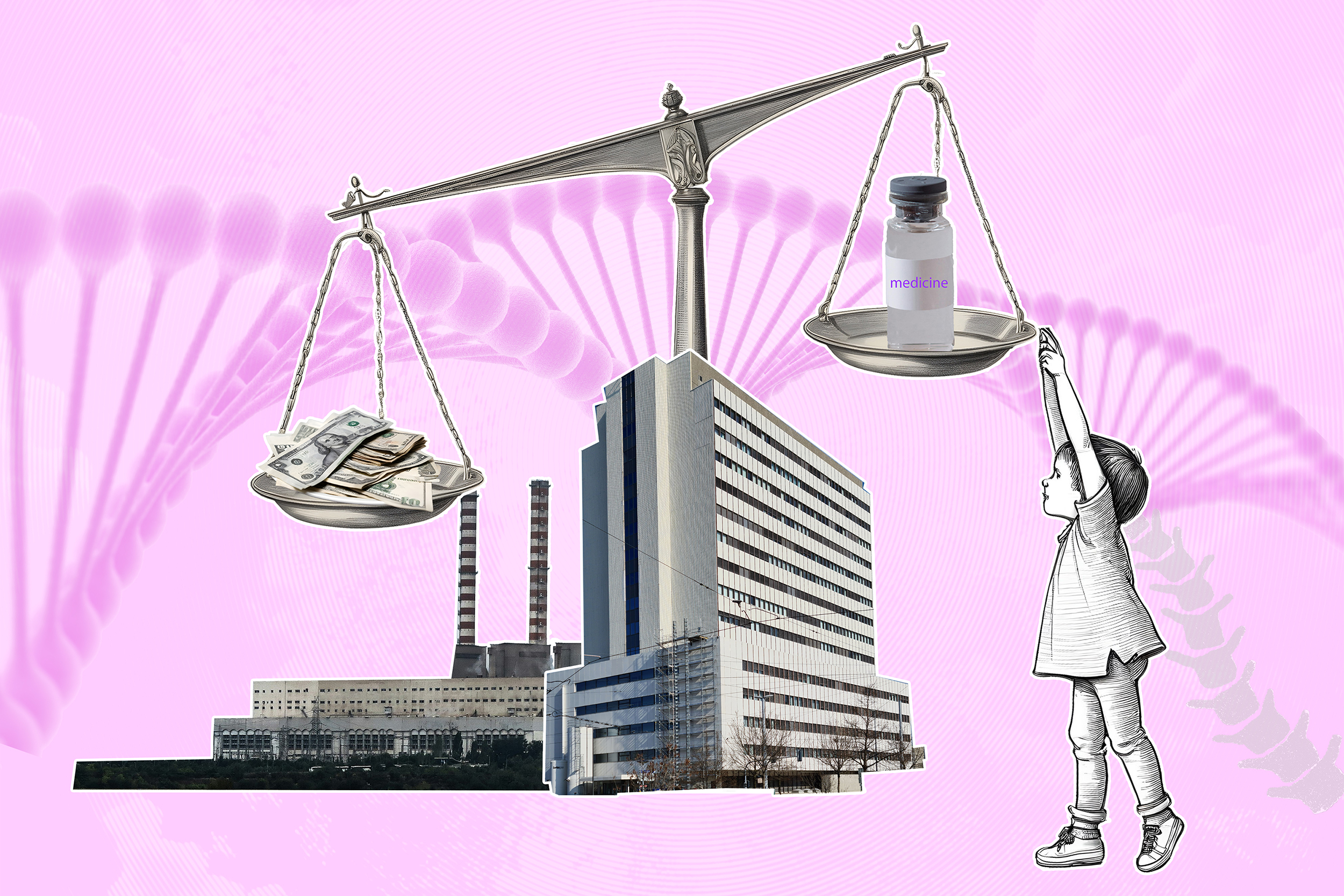

Health equity campaigners were critical of the adopted text, which they say doesn’t put enough pressure on the pharmaceutical industry to lower prices and increase medicine access. They nonetheless welcomed a decision which put the rights of rare disease patients on the global health agenda.

Either no drugs or expensive ones

The resolution comes amid growing concern about access to life-saving treatments for rare diseases, some 70% of which are genetic.

Drug development takes decades of investment for research and testing, which pharmaceutical companies usually recoup through sales. But the inability to scale rare disease drugs due to the limited number of patients for each condition has meant there is little appetite from companies to pursue development of such drugs.

Laws such as the Orphan Drug Act launched in 1983 in the US, that provide incentives such as extended monopolies, have helped drive investment in rare disease drug development.

Before 1983, only 38 orphan drugs were approved by the FDA. Since then, more than 550 medicines to treat rare diseases, those that affect fewer than 200,000 Americans, have been approved for over 1,100 indicationsExternal link. Orphan drugs accounted for 72% of new drugs launched in 2024 up from 51% in 2019, according to the health data firm IQVIA.

Even as the number of drugs rise, some 95% of diseases still lack disease-specific treatments, leaving patients to rely on physical therapy and other health interventions that only address symptoms.

More

Gene therapies’ moment of reckoning

François Lamy is the father of a boy with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, a genetic condition that leads to loss of muscle function, and the vice president of AFM-Téléthon, a French patient association focused on finding cures for rare genetic disorders. The latter was instrumental in funding early research of gene therapies, which can modify a person’s DNA to treat diseases.

Lamy said that despite incentives it is still challenging to attract pharma companies to develop new drugs for diseases – some of which have only 10 patients in the world.

“We have done a lot of early research for drugs to make it easier and cheaper for companies, but we still struggle to find a pharmaceutical partner to develop and bring treatments to market,” Lamy told SWI on the sidelines of an event hosted by RDI. That has left research that could change lives stuck in academic labs.

And, for those diseases that do have treatments, their prices are often astronomical. The latest example is the gene therapy Lenmeldy, which treats a rare inherited disorder that affects the brain and nervous system. It was launched last year by Orchard Therapeutics for at a record-high price of $4.25 million (CHF3.51 million) for a one-time treatment.

Companies argue the prices reflect the value the therapies bring to patients and cost savings to health systems from reduced hospital stays, but they are far out of reach of patients in low-income countries.

“Healthcare expenditure by low-and middle-income countries is very low, and there is no reimbursement programme, so the out-of-pocket expenditure is humongous and therefore most of the patients are not able to afford the drugs,” said Chetali Rao, a scientific and legal advisor to the Third World Network in India, in a side event at the World Health Assembly, hosted by Doctors without Borders.

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

In India, for instance, the only treatment approved for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a genetic disease that can cause fatal muscle loss, is ridisplam, sold as Evrysdi by Swiss company Roche, at a price of $173,000 per year in India according to media reports.

While it is currently approved in more than 100 countries and has been used to treat some 16,000 people, only around 165 people in India have received it. Some 3,200 babies are born with SMAExternal link each year in India, meaning only a minority of patients is treated.

A generic manufacturer and two patients are legally challenging Roche to loosen patent protection to allow cheaper version from other producers. A Roche spokesperson told SWI that it is committed to “sustainable access” and has offered the Indian government a “tailored solution” to pricing.

Beyond medicine

The challenges in many low-and middle-income countries go beyond medicine. It takes 4-6 years on average to be diagnosed as patients are passed from one specialist to the next searching for answers.

It is estimated that some 40% of peopleExternal link never even get a diagnosis. Newborn screening for rare diseases isn’t mandated in many countries, and advanced genomic sequencing to identify genetic mutations aren’t available in low resource locations.

This has also left huge gaps in data on how many people actually have a disease. Many countries also face shortages of specialists, including speech therapists and genetic counsellors.

“Access to medicine is important, but there are a lot of other things that are needed such as support for caregivers,” said Miza Marsya Roslan, a 27-year-old from Malaysia who has SMA and is the vice secretary of SMA Malaysia Association.

Adoption of national plans for rare diseases have been unequal across the world – with some countries lacking databases to track conditions while others cover treatments – but public policies are slowly catching up.

Malaysia, whose Minister of Health spoke at the event hosted by RDI, launched a rare disease framework in 2018 and guidelines on orphan drugsExternal link in 2021.

Spain, which brought the topic to the international stage together with Egypt, has a national policy for rare diseases since 2009.

Switzerland only adopted a national policyExternal link on rare diseases in 2014, which includes goals on access to diagnosis and treatment. The number of people with rare diseases in the country is estimated to be over half a million – more than those living with diabetes.

Roslan hopes that the WHO resolution will spur more countries to take rare diseases and the needs of patients more seriously. “With this resolution, we are really hoping for equity and that young people can really integrate into society,” she told SWI. “We just want to be able to achieve our potential.”

While the creation of a global action plan is critical and health equity campaigners hope it’ll bring more attention to prices and access, the decision is non-binding and will depend on the will of governments.

“The resolution alone won’t change lives,” said Mohamed Hassany, assistant minister for public health projects in Egypt. “Our goal is to translate [it] to national agendas.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.