Multicultural soap inspires Swiss artistic creation

The Swiss artist Beat Zoderer hoarded bars of soap – yes, soap – as material for his latest art project. He perceives them as a mirror of a multi-ethnic metropolis and created a new work on that basis, The London Soap Opera.

The route to Beat Zoderer’s temporary studio in London leads past jackfruit and caftans, papayas and kurtas, dates and djellabas. It is easy to work out the composition of the population from the bewitching range of goods on offer: Tower Hamlets in London’s East End is home to more Bangladeshis (32%) than white Britons (31%), and they rub shoulders with Pakistanis and Somalis as well as immigrants from India, the Caribbean, Ghana, and Kenya and their descendants.

Here there are more than 50 mosques and Indian restaurants cook halal – i.e. according to Muslim rules, while fashion and cosmetics espouse the beauty ideals of the Hindu-Indian, Caribbean, African and western worlds as well as chaste Muslim rules.

Zoderer has landed “somewhere between Karachi and Dhaka and Bombay,” he says as he opens the door to his studio on Smithy Street. The Zug cultural foundation Landis & Gyr has allocated it to him as part of an artist’s residency. He is visibly stimulated by the multi-ethnic bustle of the city on his doorstep.

One thing in particular caught his attention: the huge range of soap bars. “I’ve never seen such variety as there is here,” he says. Between Whitechapel and Bromley, Banglatown and Bethnal Green, soap bars made of vegetable and animal fats with a myriad of fragrances can be found in all colours and shapes. But he says that in one beauty salon in particular, in Mile End, he came across an almost limitless array of soaps, in between nail sets and artificial hairpieces. “I was interested in the consistency and the range of colours,” he says. “I let the material guide me.”

That was the starting point for his latest art project, The London Soap Opera.

His decision to leave his Swiss homeland, a haven of cleanliness and order, for one of the more chaotic parts of London – and then to begin hoarding soap, of all things, has elicited a few ironic remarks, including from the Mile End Indian shopkeeper. For Zoderer, however, visiting the chemist’s shop was the equivalent of a trip to an art supply store for other artists. The colour palette was all that the artist, for whom colour is a central component of his work, could have wished for.

Everyday objects

Since the 1980s, Zoderer’s art has taken inspiration from everyday materials. His objects and installations are tinged with social criticism. Aged 67, he is a trained structural draughtsman who is often treated as a descendant of the Zurich Concretists – an art movement that sought to disassociate itself from realism – because of his works focused on colour, form and patterns. But in contrast to the Concretists, he works with the flotsam and jetsam of everyday life. Wooden beams and metal slats. Plastic file covers and ring binders.

He used ring binders in a work making fun of the Swiss love of order. In 1984, he also created Billig Bill (Cheap Bill) a work satirising an exhibition poster by the father of Concrete Art. He cut wooden versions of the four triangles that formed Bill’s precise square painting and simply folded them outwards. This is Zoderer’s way of bringing to life what he calls a “democracy of materials”.

From his foraging expeditions for soap, Zoderer brought home bars of green, yellow, white, red, blue and black. They are transparent or opaque, monochrome or marbled, oval, rectangular, square or circular. In work that is almost meditative by nature, he carved them into miniature sculptures in the ancient art of glyptic, or stone carving. His sketchbook, lying open on the table, contains dozens of small form studies. These were his starting point, but he interpreted them freely.

Zigzags, semicircles, circles, triangles, cubes, concave and convex shapes, mini labyrinths and concentric rosettes like desert roses compose The London Soap Opera. It is a 72-part series of miniature reliefs that now hangs in neat rows in his London gallery, Bartha Contemporary in Notting Hill. This creation is akin to a mini-retrospective of his vocabulary of form, observes his dealer of many years, the Swiss gallerist Niklas von Bartha.

In the post-colonial metropolis, the soap bars explore a tangled subject with broad cultural-historical scope. Soap bars were invented in their present form by Arabs in the seventh century and made of heated fats, oils and alkaline salts. They were scorned in the Middle Ages, then rediscovered, and manufactured and marketed for mass use. Soap bars now serve as a mirror of the multi-ethnic capital city of 9 million, reflecting cultural and social ideals.

There is, for example, Fair & White, made with olive oil that has melatonin-reducing properties and lightens the dark complexion of women (and men) who seek to conform to western ideals of beauty. Or Crusader, which is supposed to prevent inflammation and boils thanks to its antiseptic properties. There are soaps made with argan oil, with shea butter or papaya enzymes, or the Aleppo soap made from olive and laurel oil. But soaps also carry the scent of their respective homelands – the Maghreb, West Africa, Philippines or Syria – into exile. Soaps are bearers of memory.

Civilising ‘savages’ with soap

At the same time soap reflects and records the history of the former colonial power and its self-image. “Soap is Civilisation” was once a slogan used by the British company Unilever. The success of the English Level brothers, who founded the Lever Brothers soap factory in northwest England in 1885, was closely linked to colonial exploitation.

In 1908, they began operating their first colonial palm oil plantation in the Congo, for use in soap production. Modern soaps were based on the innovative use of palm oil instead of tallow (animal fat). It was only via colonisation and exploitation that Europe gained access to the miracle ingredient – and to a booming business.

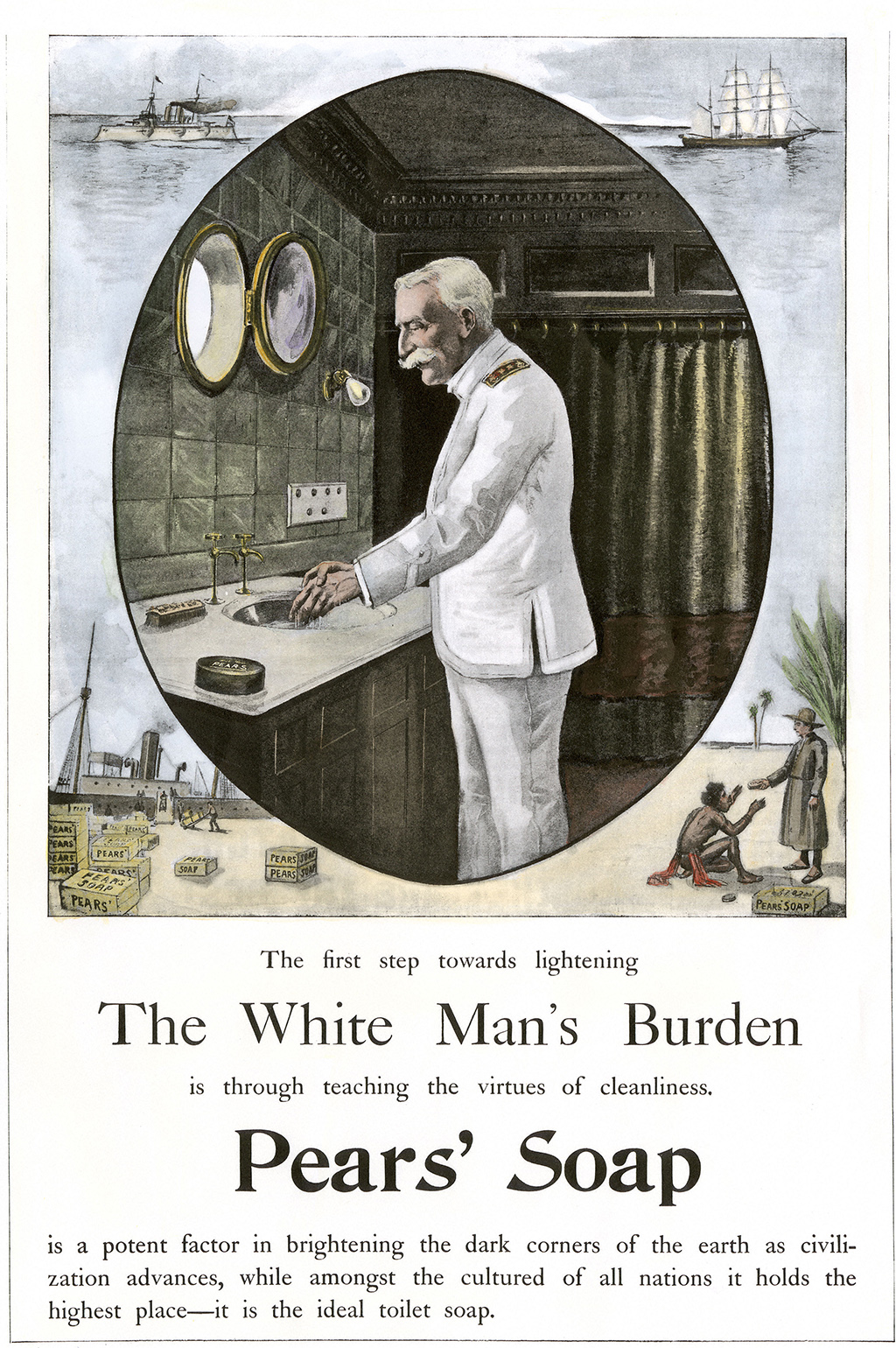

Even before that, in Victorian society, soap had mutated into a fetish object to which almost miraculous properties were ascribed. The producers of Pears, who began manufacturing their soap near Oxford Street in London in 1807 as the first mass product, made ads trumpeting the civilising effect of washing. “Soap consumption is a sign of wealth, civilisation, health and the purity of the people”, their slogan claimed.

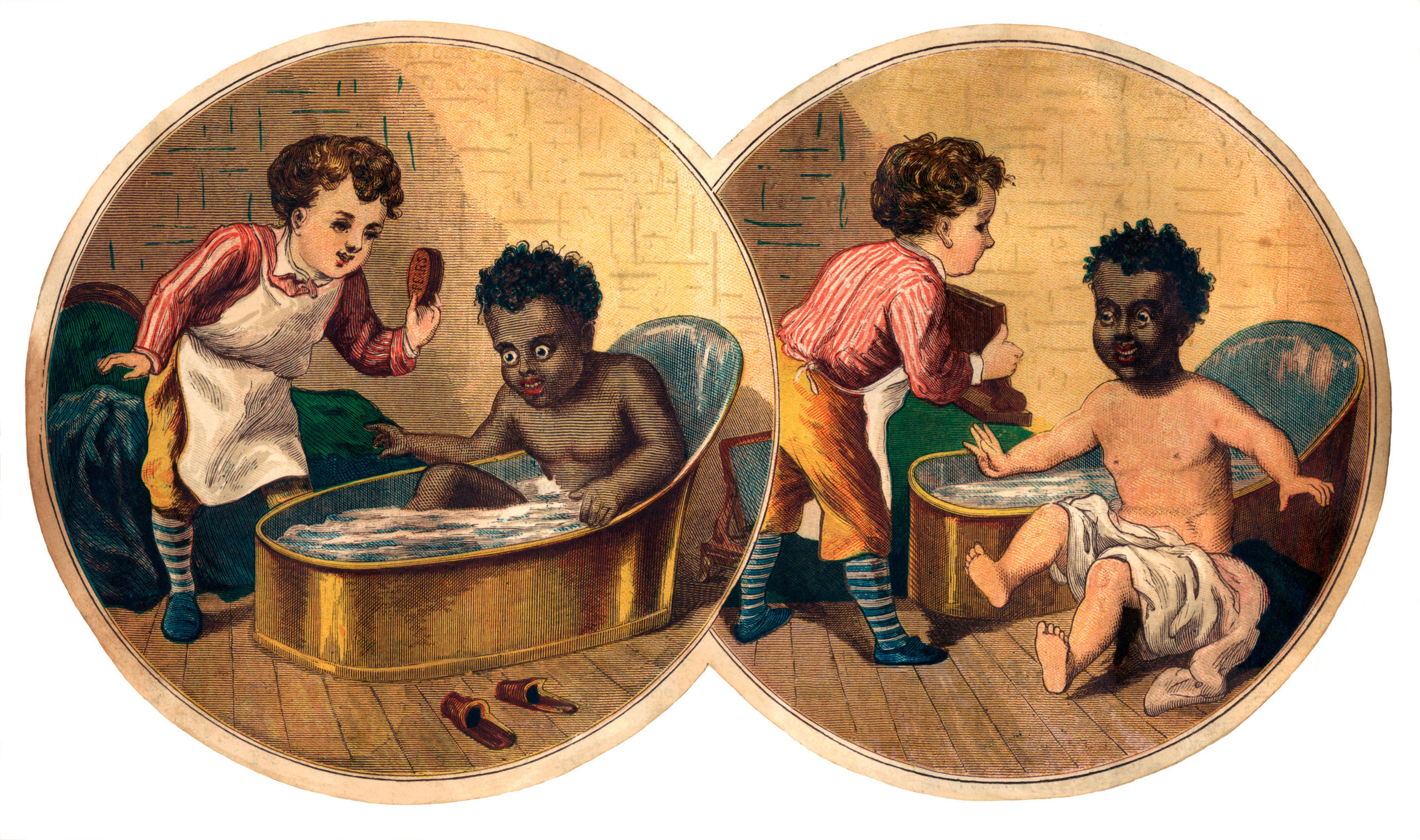

It was nothing less than a question of civilising “savages” with soap. Magazine advertisements suggest that soap used to wash black children can turn them white. Magazine advertisements even invoked Rudyard Kipling’s ideologically charged poem, The White Man’s Burden, and soaps were touted globally as a sign of Britain’s evolutionary superiority. Colonial subjects had to submit to the hygiene rules of the imperial power – for their own good, of course.

The design of the packaging was also a part of the promise of cleansing. Zoderer unfolded the soap boxes and neatly glued them to paper, where they look like Constructivist art works. He also kept a list of the names and ingredients of the 72 soaps. They are called Eden and Madam Ranee, Faith in Nature and Clear Essence, and their ingredients reflect an astonishing breadth of traditions and preferences.

Many of the more exotic scents are not unknown to Zoderer. Frankincense and myrrh, for example, remind him of bus journeys through Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq. But more than the scents, the Islamic vocabulary of forms has stayed with him. Calligraphy, the organic form of arabesques, the architecture of mosques, but above all the non-representation of Allah contributed to Zoderer’s understanding of abstract forms.

What fascinated him about Sufism was the coexistence of ecstasy and order. “Islam, and not the Concretists, brought me to abstraction,” he says. This is another reason why he does not feel at all foreign in the lively disorder of London’s predominantly Muslim East End. On his travels through India, Zoderer says, he learned how to make something out of everything.

Even soap.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.