Battling the rising tide of fake medicine

Sales of counterfeit drugs are booming around the world, putting thousands of lives at risk. Why is it so hard to stem the tide of fake medicine?

To the naked eye, the two pills of the anti-diabetic medicine Janumet look identical. They are both embossed with the number “577” in the same font and size. Only when Stéphanie Beer, a forensic scientist at the pharmaceutical group MSD, puts them under a 3D macroscope do the miniscule differences appear. On one pill, the number “577” is etched at a marginally shallower depth than on a genuine tablet produced at an MSD factory.

“To laypeople, counterfeit medicines are often indistinguishable from the originals,” Beer said during a media tour of MSD’s forensics lab in Schachen, southwest of Zurich. “Without putting the original next to it, it’s hard to see that it is a fake.”

Forensics experts in the product integrity team at MSD, known as Merck & Co. in the United States, are trained to look for such details. They have backgrounds in forensic chemistry and counterfeit drug detection. Some have worked for Interpol and other crime-fighting agencies.

Counterfeit-medicine trafficking is one of the world’s fastest-growing criminal enterprises. Analysts estimateExternal link the global market to be worth between $200 billion (CHF180 billion) and $432 billion annually. This makes fake pharmaceuticals the number one illicit activity, ahead of other underground economic activities such as prostitution, human trafficking, and illegal arms sales.

Do you want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

Although India, the largest exporter of generic drugs, is believed to be the biggest single source of falsified medicines, it isn’t the only perpetrator. Most of the 278 samples investigated by MSD’s lab in Schachen in 2023 came from Turkey, Ukraine and Egypt.

Accurate data on the total number of fake drugs and vaccines circulating globally is not available, but the Pharmaceutical Security Institute, an organisation made up of the world’s 40 largest pharmaceutical companies, reportedExternal link a 38% jump in the trafficking of counterfeit medicine across 137 countries from 2016 to 2020. From 2021 to 2022 alone, there was a 10% increase in reported pharmaceutical crime incidents, including counterfeit medicines. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimatesExternal link that about 10% of medical products circulating in developing countries are falsified or substandard.

Experts say these numbers are just the tip of the iceberg.

“We’re getting better at detecting falsified medicines through measures like improved traceability, but the problem isn’t diminishing,” said Cyntia Genolet, a specialist in counterfeit drugs at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA), a Geneva-based industry lobby group.

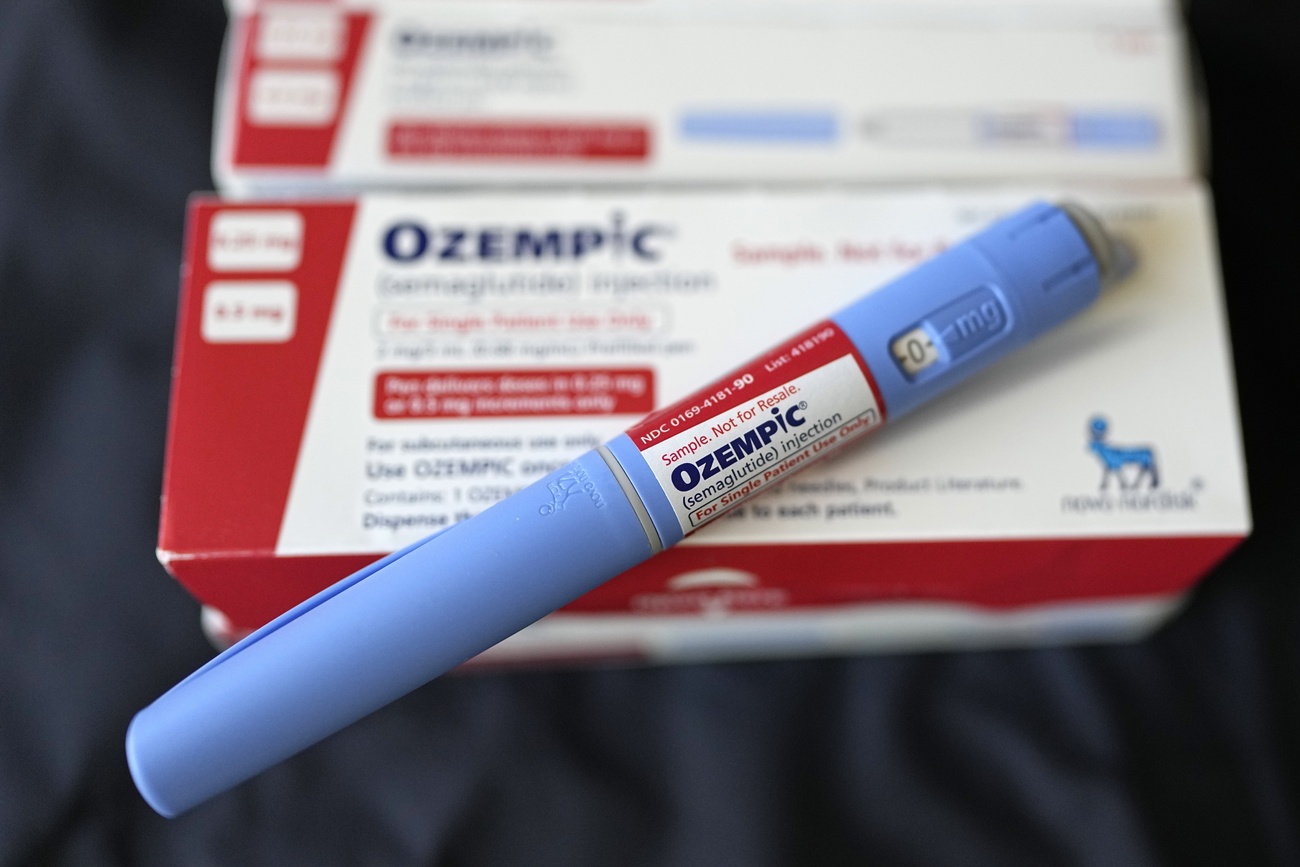

It’s not only popular lifestyle drugs such as Viagra, a pill to treat erectile dysfunction, that are being counterfeited. Authorities are increasingly finding falsified antibiotics and pain medication, such as fentanyl, as well as cancer therapies and weight-loss drugs like Ozempic. Some contain harmful chemicals. Others lack any active ingredient or have the wrong dosage, which can have dangerous and even deadly effects on patients.

Fake medicines kill more than 500,000 people a year, according to the United NationsExternal link. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism foundExternal link that falsified or substandard versions of a childhood cancer drug had spread to over 90 countries, putting an estimated 70,000 children at risk from the ineffective treatment.

The WHO differentiatesExternal link between falsified and substandard medicine. Falsified medicine refers to medical products that deliberately or fraudulently misrepresent their identity, composition or source. There are four types of falsification: counterfeiting (those that don’t comply with intellectual property rights), tampering, theft and illegal diversion. A substandard medicine is an authorised medical product that fails to meet quality standards or specifications, or both.

Europe’s cancer scare

Fake medicine has been a problem for decades, but Europe got a wake-up call around 2010. Counterfeit versions of Avastin, a monoclonal antibody cancer drug sold by Swiss pharma giant Roche, emerged in US and European markets. Authorities scrambled to ensure patients weren’t harmed and to investigate how the knock-offs wound up on hospital shelves.

“European regulators realised that falsified medicine wasn’t some far-away problem. It was right here in mature markets in Europe,” said Nicolas Florin, who heads the Swiss Association for the Verification of Medicinal Products (SMVO).

The 46-member Council of Europe, which includes Switzerland, adopted the Medicrime Convention in 2010, which criminalised falsified medicine and led to the creation of the European Union (EU) Falsified Medicines Directive in 2011. The directive sets out harmonised measures to increase the security of the manufacturing and delivery of medicines in Europe and to protect patients.

In 2019, the EU unveiled a verification system that requires drugmakers to add a 2D data matrix with a product code, an individual serial number, a batch designation and an expiry date to every packet sold in Europe. Pharmacists scan the packets to verify they are in the system. The system has been adopted on a voluntary basis in Switzerland but is expected to become mandatoryExternal link by 2026.

More than 200-300 million scans are performed per week across Europe. On top of this, Interpol, medicines regulators such as Swissmedic, and law enforcement agencies seize and investigate counterfeit drugs at European borders and those sold online. Last year, the Swiss Office of Customs and Border Security seized over 6,600 illegal drugs.

“The chances of a falsified drug making its way to a patient at a hospital or pharmacy in Switzerland are less than 1%,” said Florin. The figure is slightly higher for other parts of Europe but still very low. “The EU system has sent a message to criminals that if they try to enter the European market, they will get caught.”

The EU directive also requires online pharmacies to display a common logo, but it can be easily copied, and consumers frequently fail to verify them. Interpol shut down 1,300 websites alone during a week-long operation to crack down on illicit medicine.

The shortages problem

Although EU patients are now better protected, fake medicines are still widely available, especially in developing countries that don’t have the infrastructure or funding to carry out the kind of checks that are now standard procedure in Europe.

Sky-high prices and a growing shortage of many drugs and medical supplies, exacerbated by the Covid pandemic and the explosion of unregulated online pharmacies, are compounding the problem.

Doctors in Kenya interviewed by SWI swissinfo.ch during a reporting trip two years ago said they often look for alternative suppliers online for cancer drugs that aren’t available or affordable locally. “Sometimes we don’t see any change in the patient after administering the drug,” said one doctor. “It could be like giving them sugar water. There’s no way to tell.” In some parts of AfricaExternal link and Asia, up to 70% of medicines are estimated to be counterfeit.

While the pandemic is over, factors including trade barriers, manufacturing problems and the war in Ukraine have perpetuated shortages nearly everywhere. Prices for some new drugs are also so high that insurance providers have refused to reimburse them, leading patients to look for alternative suppliers.

+ Why Switzerland is running out of pharmaceuticals

“Fundamentally, we are creating the supply. Criminals are fulfilling our demand,” said Mike Isles, who leads the industry-funded European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicine that campaigns for supply-chain action to fight counterfeits. “When a medicine is out of stock and you are a deeply vulnerable, compromised cancer patient, you will try just about anything.”

Illegal internet pharmacies, social media platforms, and online marketplaces are ready to meet that demand. Half of all medicines bought on websites that conceal their physical addresses are thought to be fake, according to the WHO. Some studiesExternal link suggest the share could be much higher.

The rise of online pharmacies has made it much “easier for counterfeit medications to reach consumers”, said Mario Ottiglio, a spokesperson for Fight the Fakes, an alliance of organisations raising awareness of falsified medicine.

Online offers for Ozempic are rampant and despite warnings, European regulators say they are powerless to stop falsifiers outside their jurisdiction, according to a reportExternal link by Politico.

Global response falls short

A coordinated international effort to crack down on counterfeit medicines has so far fallen short. The WHO offers guidance and technical support to regulators and issues alerts about specific products, but the Geneva-based health body relies on reports and evidence from national authorities and doesn’t have the capacity or mandate to investigate cases and punish offenders.

The UN children’s agency, UNICEF, has led a massive effort to introduce technology to verifyExternal link vaccine donations. The newly formed African Medicines Agency has also made surveillance and quality control a priority, but lacks the resources needed to stamp out illegal drugs.

More

Wanted: Pharma super cops

Big pharmaceutical companies like MSD have invested in labs, blockchain, covert technology like invisible printing, and portable scanners to help authorities investigate suspicious products. MSD’s forensics lab in Schachen opened in 2018 and is one of three in the global MSD network. The EU Intellectual Property Office estimatesExternal link that pharmaceutical companies lose about 4% of sales due to counterfeits.

Novo Nordisk announced in March that it is boostingExternal link efforts to crack down on falsified versions of Ozempic, which have surfaced in at least 16 countries in the last year as the Danish multinational struggles to keep up with demand.

But companies are mainly focused on protecting their brands and their products and say they don’t have the authority to seize counterfeit drugs and hold falsifiers accountable.

“Companies and regulators know more about falsified medicine and where they come from. But the problem isn’t going away,” said Florin. “It’s a big business, which makes it attractive to criminals.”

Edited by Nerys Avery/gw

Correction: On July 31, 2024 we updated this article to clarify that the EU medicines verification system is still voluntary in Switzerland. A clause on verification of safety features on medicine packaging has been added to the Swiss therapeutics law but the implementation process has not been finalised.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.