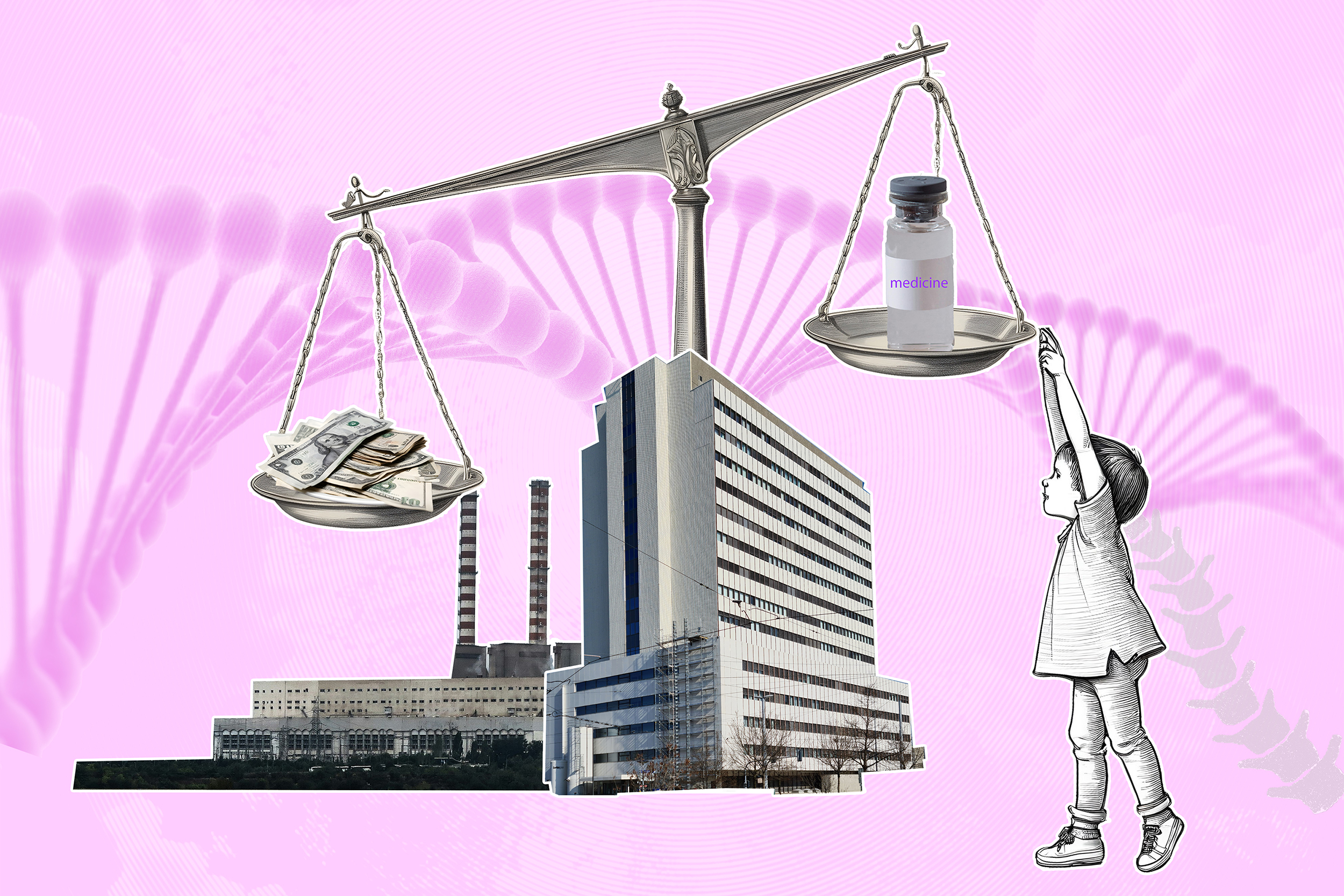

Drug pricing: Swiss expert calls for more transparency

As the global debate intensifies over whether multi-million-dollar drugs are worth the money, big pharma needs to improve transparency over the pricing and therapeutic value of potentially life-saving new medicines, says law and medicine expert Kerstin Noëlle Vokinger.

SWI swissinfo.ch: It seems no one is happy with drug prices. Pharma companies argue efforts to rein in prices will thwart innovation, while patients and health authorities are trying to deal with more drugs at higher prices. What’s at the heart of the problem?

Kerstin Noëlle Vokinger (K.V.): First, this is not a new problem. We have been debating what is a fair price for a long time, but the problem has just accelerated and gotten worse. One issue is we have more drugs with high prices. Yearly treatment costs can be more than $150,000 for some drugs and then we have gene therapies that cost over $2 million. This is a new dimension.

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

The other issue is that the evidence on the efficacy of many drugs has decreased at the time of approval. This is partly because the US as well as Europe, Switzerland and other countries are using accelerated approval pathways more often. These aim to incentivise the development of medicines that have a high therapeutic value for patients and make them accessible quickly. Studies have shown that although manufacturers are supposed to provide additional evidence later on, they don’t always do it or delay doing so.

Less evidence but higher prices is a toxic combination for patients and society.

SWI: Why don’t governments push for more evidence?

K.V.: There is pressure on governments to make new drugs available to patients.

It’s not surprising that high-priced drugs often go hand in hand with less evidence because it often concerns drugs for the treatment of deadly diseases. Actually, we are investing to some extent in hope. This is understandable because, for example, patients with rare or deadly diseases, need treatments.

But the problem is how can you negotiate a drug’s price when you don’t know its real therapeutic value? The real therapeutic value may end up being lower than estimated at the time of approval and we have to be aware that these drugs can have serious side effects. It is important that the threshold for evidence doesn’t decrease further.

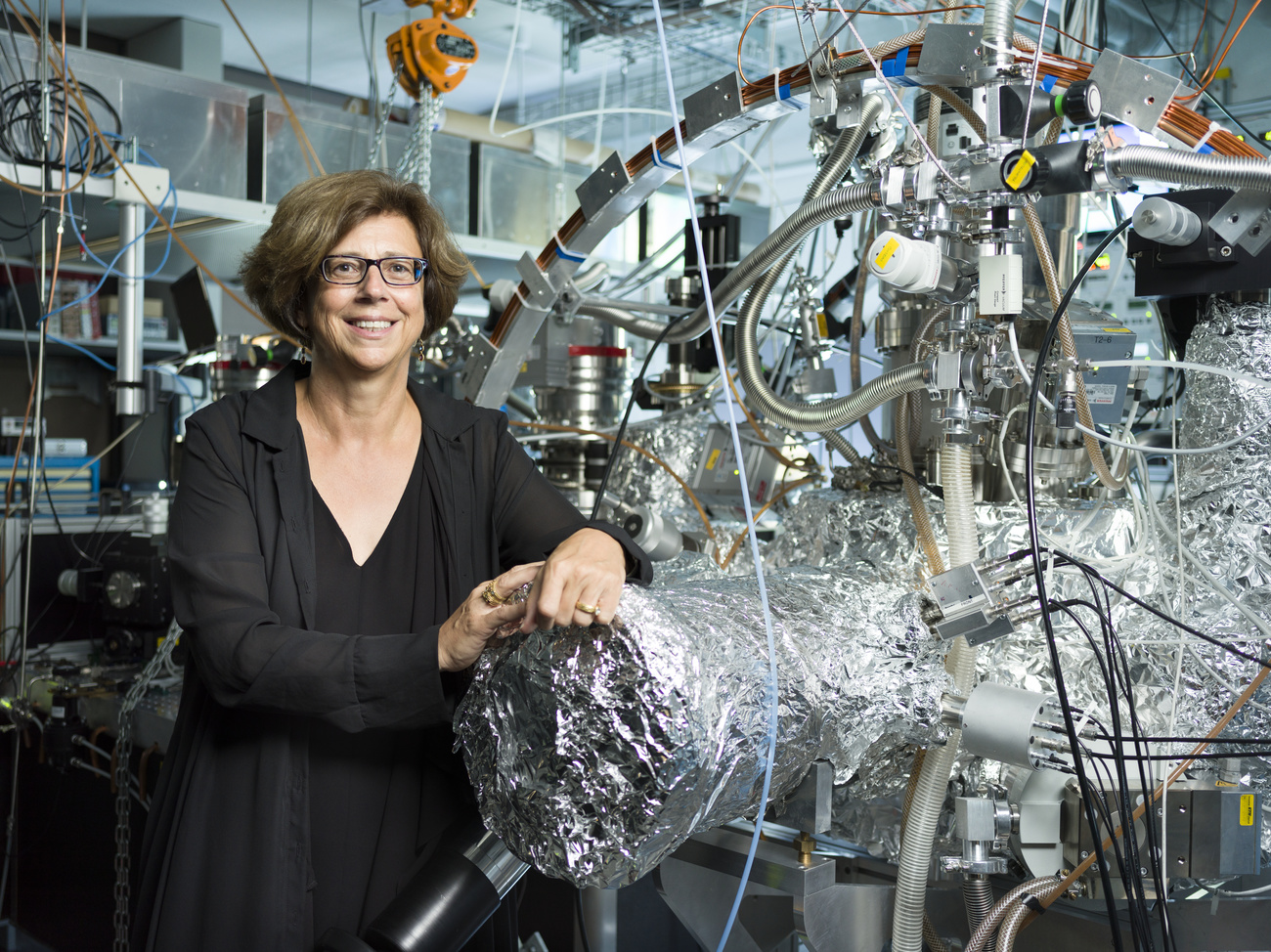

Vokinger holds doctorates in both law and medicine from the University of Zurich along with a Master’s degree from Harvard Law School. In 2022, she was awarded the Swiss Science Prize Latsis, which goes to a researcher under 40 years old for outstanding achievements in scientific research.

One of Vokinger’s major research areas is how to improve access to new medical technologies. She also advises governments and international organisations on the subject.

She currently has a dual professorship hosted jointly at the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Zurich, where she holds an academic chair in regulation in law, medicine and technology.

SWI: How should health authorities deal with this dilemma?

K.V.: We have to be more cautious when applying accelerated approval and really focus on those drugs that have the highest potential for high therapeutic value. It takes a lot to bring innovation that really benefits patients onto the market. Companies want to be rewarded for this. They are profitable when they bring drugs on the market earlier, but the lack of evidence should also be reflected in the price.

SWI: Some governments and manufacturers are signing agreements where payment is tied to whether a drug actually achieves certain predefined patient outcomes. Is this a possible solution?

K.V.: These kind of managed entry agreements make sense in some situations, but we have to be careful that there aren’t loopholes that increase costs and actually lead to ineffective or even harmful drugs being put on the market.

+ Swiss study sees no link between cancer drug prices and patient benefits

The big problem with many of these agreements is there is no transparency, which may result in higher prices. Studies have demonstrated that confidential rebates result in higher prices and longer negotiation processes.

SWI: Many countries including Switzerland have become more secretive about drug pricing over the last decade. Why has it been so difficult to bring more transparency to prices?

K.V.: We are finding ourselves in some sort of a prisoner’s dilemma – if one country only thinks about themselves because they believe secrecy will help them receive a lower price, the whole system won’t work anymore because then other countries also lose the motivation to be transparent. Many countries around Switzerland such as England and France have been getting less transparent for a while so Switzerland started to think it should also be part of the game and started introducing confidential discounts. The Swiss parliament is even considering changing the law to allow such discounts to become the rule rather than the exception.

More

How drug prices are negotiated in Switzerland and beyond

This creates a major imbalance of power because it becomes difficult for health authorities to argue for a certain price when only the manufacturer knows what the other countries are paying. Beyond that though, society and patients have a right to know how much a treatment costs especially since they are paying into the system. This is why I really believe transparency on drug prices should be mandatory.

SWI: You’ve done extensive research on the price of cancer drugs. One interesting finding is that price doesn’t always correlate with clinical benefit. Should efficacy determine prices?

K.V.: There are two elements. One is what is the therapeutic value of a drug. This has been based on clinical endpoints like overall survival in the case of a cancer drug. There are some calls for more measures such as the loss for society if someone isn’t able to work because they are sick. While I believe that these determinants are relevant, I worry about considering them in the price negotiation because the more we bring in elements that are hard to measure, the more difficult it is to assess and compare the value of drugs.

Once we know the therapeutic value of a drug, and let’s assume it has a higher value than the comparator drug, the next question is should it cost 100 francs or 1 million francs more than the comparator drug? High value drugs should be more expensive than low value drugs, but we also need to ask how much higher they should be. The UK is already doing this. The system is far from perfect, but it links the value with the price.

+ Pharma blasts US move to rein in drug prices

SWI: As part of the Inflation Reduction Act, the US government plans to start negotiating prices for some drugs covered by the state-run Medicare insurance programme. This is an attempt to bring down prices in the US but has angered many pharmaceutical companies. How much of a revolution is it?

K.V.: It’s pretty revolutionary after having a free market with free pricing for such a long time. From a European perspective, negotiating prices for just 10 drugs each year that aren’t even new [which is what state-run Medicare will do], seems like a small step.

Ten drugs a year is an important starting point but as US President Biden already said, it should expand further. The US is the biggest pharmaceutical market in the world and it’s where companies usually set their prices so it will have a huge impact.

SWI: What effect will this reform have on drug prices?

K.V.: The aim is that it will bring down prices because I think everyone agrees that drugs in the US are overpriced. Now it depends on what loopholes are included and how the price will be negotiated.

SWI: Pharmaceutical companies have argued that the US move, along with other efforts in Europe to rein in prices, could have a negative impact on innovation. What’s your view?

K.V.: This is a statement without proof. The research and development costs for drugs are not even transparent, we only have broad approximations. One important step would be for companies to be transparent about the research and development costs, including the amount of public funding they receive.

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.