What triggers a SLAPP lawsuit in Switzerland? Gold does

Swiss NGO Swissaid is facing off against Switzerland’s largest refinery, Valcambi, in court this week. The trial, set to open on May 7, hinges on a report by the NGO that blew the whistle on the refiner’s business relationship with a questionable gold supplier in Dubai.

Experts see such cases as part of an alarming trend sweeping Europe: the rise of strategic lawsuits against public participation (or SLAPPs). They are typically waged by the powerful (governments and large companies) against individuals – often a journalist or watchdog NGOs – that bring to light uncomfortable truths in the name of public interest.

“It isn’t about collecting damages but rather about forcing the person into silence,” says Corinne Vella from the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, named after a Maltese journalist who was assassinated.

“One key characteristic of SLAPPs is an imbalance of power,” she tells SWI swissinfo.ch. “With corporations, it can be even more pronounced. You have a big company against a small NGO. It is usually a local NGO that uncovers the problems first. The company sees a real benefit in shutting up criticism [that may bring] damage to their reputation.”

Legal battle

This Bern courtroom drama has its roots in a 2020 report by Marc Ummel, who leads the raw materials unit at Swissaid, an organisation focused on development work and advocacy. The report showed how some Swiss refiners use intermediaries to mask the origin of gold that may be problematic.

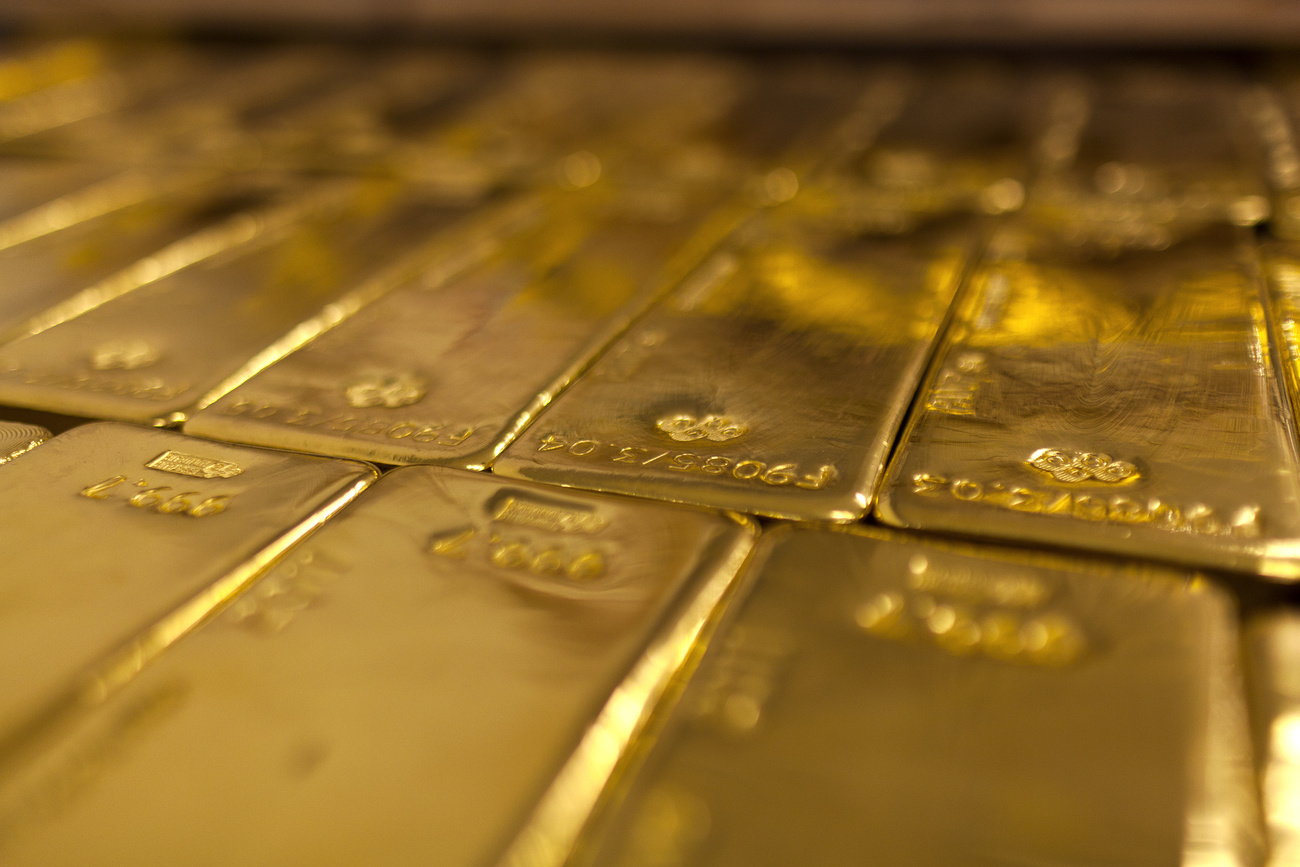

It named-and-shamed Valcambi for its relationship with Dubai-based Kaloti, which was alleged to have been involved in money laundering and procured gold from conflict zones in Africa, such as Sudan.

Dubai, which is a major hub for the global gold trade in the United Arab Emirates, imports gold from all over Africa. A lot of that gold ends up in Switzerland, which is home to four of the seven largest refineries in the world. Some Swiss refiners avoid importing gold from Dubai because it is so difficult to ascertain that it has been legitimately sourced.

In September 2020, Valcambi chief executive Michael Mesaric told the French-language daily Le Temps that Swissaid’s claims were unfounded. “These allegations are wrong,” Mesaric said, noting that Valcambi had been cleared of any wrongdoing in two audits by the LBMA – the London Bullion Market Association, the global authority on precious metals.

Despite the threat of legal action, Swissaid decided to stand by its research. Valcambi responded with a lawsuit against Swissaid for defamation. It later filed a criminal complaint against the report’s lead author, Marc Ummel, and the NGO. Swissaid is convinced that the lawsuits are baseless and just an attempt to intimidate and silence the NGO. The initial trial was set for September 2023 but was delayed for procedural reasons.

“The company has taken highly aggressive measures,” says Swissaid director Markus Allemann. “Unlike the NGO, the company has substantial financial resources and can afford prolonged and costly legal proceedings. Acting in good faith, the NGO gave the company an opportunity to respond to the allegations before publishing the report. However, the refiner only provided partial responses.”

SLAPPs on the rise

The case meets the criteria for a SLAPP in the assessment of CASE, a coalition of non-governmental organisations from across Europe united in recognition of the rising threat posed to public watchdogs by SLAPPs. This trend is complicating the work of journalists and human rights across the world. Switzerland is not immune to the problem.

CASE has registered 12 such cases in the Alpine nation since 2010, when its tracking began. This compares to 135 on the high end (Poland) and zero in countries like Norway and Liechtenstein. The Swiss tally for 2010-2023 is lower than in neighbouring France (90), Italy (62), Germany (14) and Austria (18). Most lawsuits are based on national defamation laws. Valcambi is counted as a SLAPP for many reasons, according to Francesca Borg Costanzi, who is the coordinator of CASE. This includes the aggressive tactics used and the fact that not only was the organisation targeted but also the individual, Ummel.

“The legal system in Switzerland is rather favourable for SLAPPs,” notes the CASE country report for Switzerland. “There are currently no mechanisms or laws that would allow for a quick identification of a SLAPP-case and a rapid dismissal of a complaint that has been identified as a SLAPP.”

The year 2022 was a record one for SLAPPs. CASE’s database increased from 570 cases in 2022 to over 820 cases in 2023 –161 of which were lawsuits filed in 2022, a significant jump compared to the 135 filed in 2021. Journalists and human rights defenders warn that this trend hurts Europe’s standing as a beacon of democracy and press freedom.

A 2022 survey by the NGO HEKS of 11 organisations showed that intimidation lawsuits against critical NGO reports have also increased in Switzerland. While only two threats of legal action were registered between 2000 and 2010, the NGOs surveyed have been confronted with 17 legal intimidation attempts since 2010. In response, the Swiss Alliance against SLAPP was founded in the summer of 2023.

+ UN expert reprimands Switzerland over complaint against Bruno Manser Fund

It’s hard to say why such cases are becoming more common. Vella’s response: “Because they can. There is no barrier to SLAPP. There is nothing in the law forcing a plaintiff to pay damages to a defendant if it is found to be a SLAPP.”

Valcambi

Valcambi says its case is not about silencing the NGO but setting the record straight.

In September 2023, Valcambi issued a statement criticising Swiss media for its coverage of the refinery and stating it took legal action against the NGO due to the presence of “47 false statements” in the Swissaid report. In a written statement provided to SWI swissinfo.ch on Monday, Valcambi chief operating officer Simone Knobloch argued the case it brought against Swissaid should not be considered a SLAPP.

“We are not even seeking financial compensation, but only clarification that, in this case, Swissaid acted in an unprofessional and improper manner, and we demand that it cease spreading falsehoods about us,” said Knobloch, who also serves as deputy CEO. “We would have openly admitted our mistakes, if there had been any, and immediately taken all measures to address them.”

The Swiss refinery is widely considered to have a higher risk tolerance than its Alpine-based competitors. In October 2023, the refinery parted ways with the Swiss Association of Precious Metals Manufacturers and Traders (ASFCMP) over differences of opinion on best due-diligence practices. In January 2025, its membership at the Swiss Better Gold Association was suspended for six months.

Knobloch, however, says the risk appetite is “very close to zero” at the refinery, which has the capacity to handle up to 1,600 tonnes of gold per year. He noted that the company had changed auditors three times since 2020 to ensure they are above reproach and able to guarantee to all its stakeholders that it is fully compliant with all relevant rules and regulations.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

This article was updated on May 5, 2025, to include a response from Valcambi.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.