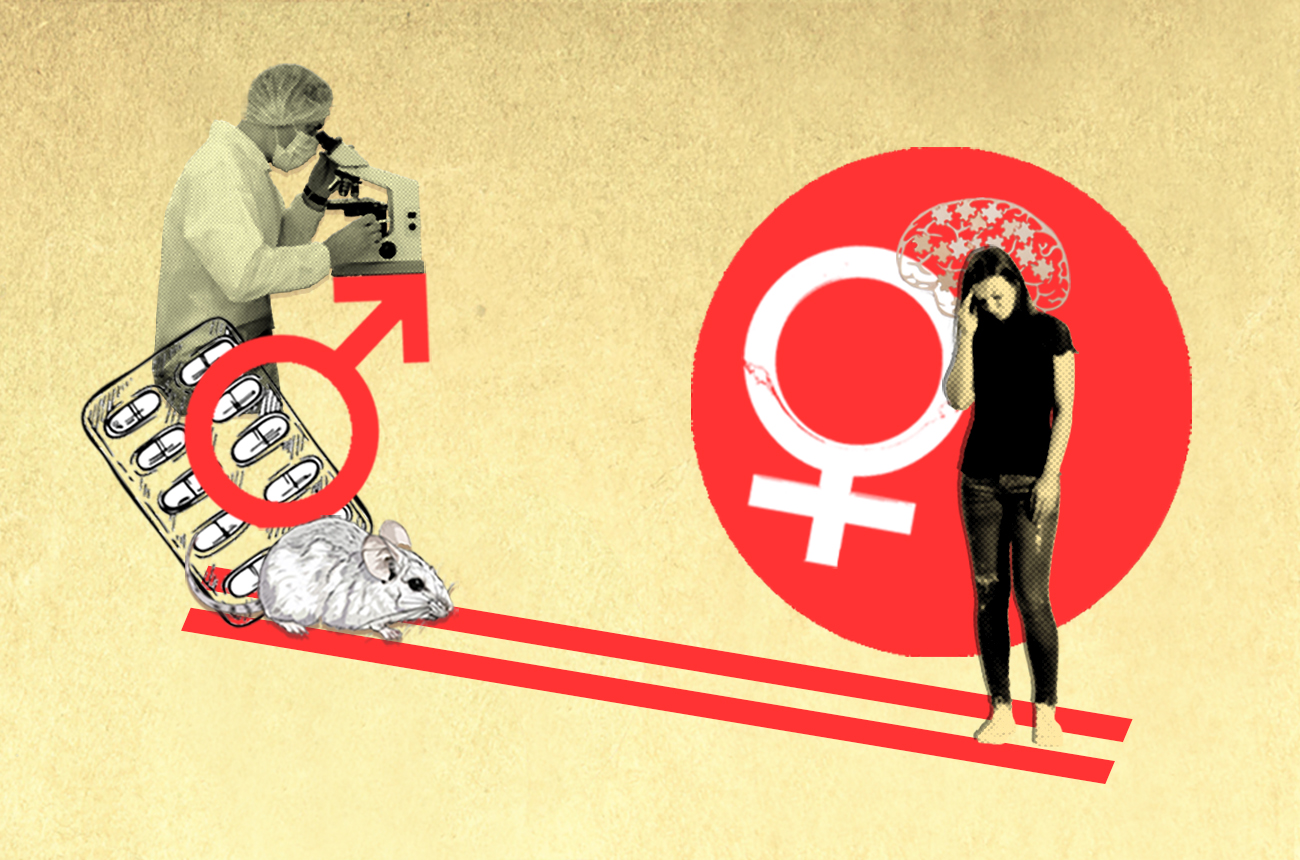

Drugmakers are finally making medicine for women

Medicine can affect women differently than men, but rarely are sex and gender considered in the development of drugs. There’s now a movement, including in Switzerland, to change this.

In July 2023 lecanemab, sold under the brand name Leqembi, became the first drug in 20 years to be fully approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for Alzheimer’s disease. The drug, which was developed by US firm Biogen and Japanese firm Eisai, works by reducing amyloid plaques that form in the brain, a defining feature of the memory-robbing illness that affects some 55 million people globally.

The pivotal studyExternal link for approval of the drug showed that it slowed cognitive decline by 27% compared to a placebo.

More

Gender medicine is also good for men

But the supplementary appendix told a more complex story. It revealed differences among the 1,700 patients in the study, some 51.7% of whom were women. The drug slowed cognitive decline by only 12% in women compared to 43% in men.

These results are difficult to interpret because the study wasn’t designed to identify differences in the drug’s impact on women and men, a spokesperson from Eisai told SWI swissinfo.ch. That would require more thought to the sample size, progression of the disease in the placebo arm, among other factors. Nevertheless, the results still raised questions for experts, especially given two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients are women.

“Leqembi is a breakthrough for Alzheimer’s patients,” said neuroscientist Antonella Santuccione Chadha, who worked for two years in the Alzheimer’s programme at Biogen and is now the co-founder of the Women’s Brain Foundation in Zurich. “But we need to acknowledge that the drug works differently for men and women and understand why.”

+ Get the most important news from Switzerland in your inbox

This is a question medicine regulators and major health funders are increasingly asking themselves. Last year, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the largest public funder of biomedical research in the country, announced a CHF11 million ($13 million) national programme to find ways to integrate sex (biological attributes) and gender (identity) into health research and medicine.

The move reflects a shift taking place elsewhere, including in the US, Canada and across Europe, to overhaul the male-dominated approach to medical research and develop drugs with women in mind.

‘Bikini medicine’

The fact that more than half the participants in the main Leqembi trial were women and the study reported gender-disaggregated data at all is a sign of progress, say experts interviewed by SWI.

Although women accountExternal link for 70% of chronic pain patients, 80% of pain studiesExternal link are conducted only on men or male mice. Men still dominate many clinical trials for diseases that disproportionally affect women.

Multiple sclerosis, a chronic disease of the nervous system, is twice as common in women. Women are also more likely to have a stroke, cardiovascular disease and autoimmune disorders such as lupus.

Rarely are study results broken down by sex and gender and reported publicly. When they are, differences in the efficacy and safety for men and women are rarely considered in the approval and prescribing information for drugs.

When women are at the centre of medical research, it’s often for diseases that affect their sex organs.

“Women’s health is broader than this idea of bikini medicine,” said Stephanie Sassman, who leads women’s health at Genentech, a subsidiary of Swiss firm Roche.

The lack of focus on gender differences in drug research has had serious consequences for women’s health. “There are hundreds of diseases where women get a delayed diagnosis, are misdiagnosed entirely, or receive a treatment or dosage that’s ineffective or even unsafe,” Sassman added.

In the past 40 years, medical products are 3.5 times more likely to be removed from the market because of adverse effects on women than on men, according to a McKinsey Health Institute studyExternal link published in January.

Even in Switzerland, which has one of the highest-quality health systems in the world, a government-commissioned reportExternal link published in May found that women receive treatments that aren’t as well adapted to them, leading to “more side effects and poorer prognosis”.

Bias from the beginning

One key reason why this women’s health gap persists is that bias is already baked into scientific models in early research, which carries over into later stages of drug development.

Until recently, researchers saw women’s bodies as smaller versions of their male counterparts. There are still 5.5 times more studies using only male animals than studies that include female animals, according to an Economist study commissioned in 2023 by the Women’s Brain FoundationExternal link.

“Some researchers are so used to using male animals and don’t even ask the question if it would be different if you studied the brain mechanism in female versus male mice,” said Carole Clair, who heads the health and gender unit at the University Centre for General Medicine and Public Health (Unisanté) in Lausanne.

There’s been an assumption that a hypothesis holds true regardless of someone’s sex, she added. But studies show this isn’t the case.

More

How gender disparities impact health

For example, a 2022 studyExternal link on the anti-ageing benefits of the generic drug rapamycin in fruit flies found it only prolonged the lifespan of females and not of males. Some clues as to why are in the waste disposal process in the female’s intestinal cells, which differs from that of males. There are also differences in the way men and women adhere to medicine, depending in part on gender norms and roles.

Even when researchers and pharmaceutical companies are aware of differences, they have often argued that including women is complicated and costly, especially given women’s fluctuating hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle. StudiesExternal link now show that men’s hormone fluctuations are also a factor in drug response.

“At the end of the day, you’re doing an experiment with a clinical trial to see whether a drug works or not. Every experiment needs to have its own associated controls,” said Ian McConnell, vice president of communications in the research arm of MSD, known as Merck in the US. It takes on average a decade and some $2.5 billion (CHF2.3 billion) to bring a new drug through clinical trials.

“The more parameters you measure, the more complicated and expensive the trial gets.”

Slow shift

Governments have become more aware of the gender gap, but they have struggled to find a way to address it while still ensuring safety, managing costs and not imposing too many restrictions on research.

In 1993, the FDA issued a guideline making clear that women should be includedExternal link in all phases of clinical drug development. This reversed a previous policy banning women in child-bearing years from participating in early trials after birth defects emerged from exposure to new drugs. Pregnant women are still excluded from most trials.

More

Innovation in women’s health comes in small doses

In the same year, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the US, which is the largest public funder of biomedical research, required women to be included in publicly funded phase III clinical trials, when drugs are tested in large populations.

The European Union followed, developing a toolkitExternal link for gender in EU-funded research in 2014.

“Just because there is a guideline doesn’t mean that it will be followed,” said Santuccione Chadha. Various studies showExternal link the number and share of women in clinical trials have increased overall but there’s been less progress when it comes to early research with animals. There’s also been little movement to analyse results by gender and use these to develop drugs tailored to women.

More

Swiss non-profit aims to break taboo of women’s brain health

Many of the policies have been vaguely worded and lacked strong enforcement. A 2018 review of 107 NIH-funded trials found that while the median enrolment rateExternal link for women was 46%, about 15% enrolled less than 30% women and only 26% reported even one outcome by sex.

Meanwhile, Switzerland has been slower to change. The Swiss National Science Foundation, which is the largest biomedical funder in Switzerland with an annual budget of about CHF1 billion, doesn’t have any gender diversity requirements.

Swissmedic has relied on international guidelinesExternal link stating that patients in clinical trials should be “reasonably representative of the population” that will be later treated by the drug. But it’s unclear how compliance is enforced.

“In Switzerland, funders have been cautious about being too directive with research. The view is that it is researchers’ individual responsibility,” said Clair. “It should be logical that you include the treatment population in your study, but if you don’t have a top-down approach to enforcing that, it may not happen.”

There is now greater momentum, partly spurred by the Covid-19 pandemic, which showed that women sufferedExternal link more vaccine side effects than men. Switzerland has revised its clinical trials law, which will come into forceExternal link in November, requiring more gender balance in research. The US FDA will also require diversity plans starting in 2025 for all phase III trials. These plans should offer more insight into why participants are recruited to a trial and how results will be analysed by cohort.

The Swiss government has also tasked Swissmedic to find ways to integrate sex and gender better into its evaluation of new medicine, with changes expected by 2029. The Swiss National Science Foundation programme should also reveal ways to bridge the gender gap in early research.

Booming market

Pharmaceutical companies are also more open, as they eye a booming market for “femtech” – products designed for women. Market research suggestsExternal link the menopause market alone could reach $24 billion by 2031.

“When you think about the whole patient journey from a women’s lens, it opens up new opportunities,” said Sassman. In 2022, Roche started ProjectX to drive investment in women’s health, looking at diversity in clinical trials but also considering factors such as fertility and menopause in how the company understands disease progression and treatment response.

These are all steps in the right direction, said Santuccione Chadha, but gender is still an afterthought in drug development.

“We really have to change the mindset so sex and gender differences are detected and discussed from the beginning,” said Santuccione Chadha. “This will make medicine that is safer and more effective for everyone.”

Graphics provided by Pauline Turuban. Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.