Medicines regulators weigh hope and hype with new Alzheimer’s drugs

Swiss medicines regulator Swissmedic is expected to decide by the end of the year whether to approve the first new drug for Alzheimer’s disease in two decades. The decision won’t be easy.

Alzheimer’s disease has baffled researchers for decades. Drugmakers have poured billions into the disease, which slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, but haven’t come out with a new drug for at least 20 years.

This changed in July 2023 when the US Food and Drug Administration approved lecanemab, sold under the name Leqembi, for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. Since then, it has also been approved by authorities in Japan, China and South Korea. The drug is the first to address both the symptoms of memory loss and what’s believed to be an underlying cause of the disease.

+ Get the most important news from Switzerland in your inbox

“Last year was a major step forward for Alzheimer’s research,” said Andrea Pfeifer, founder and CEO of AC Immune, a Lausanne-based biotech firm that has been working on Alzheimer’s therapies for over 20 years. “No new drugs had come on the market for so long that people stopped believing it was even possible to treat the disease.”

This euphoria didn’t last long in Europe. In July 2024, the European Medicines Agency review committee recommended rejecting the drug. They argued the risks outweigh the benefits, citing safety concerns such as swelling and bleeding in the brain.

A month later, the UK regulatory agency authorised lecanemab but the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which assesses drugs’ cost-effectiveness, didn’t recommend it for reimbursement. It argued the price, which is $26,500 (CHF22,300) a year in the US (and confidential in the UK) was too high relative to the benefits.

More

Drugmakers are finally making medicine for women

Alzheimer’s patients in Switzerland are now eagerly awaiting a decision by the Swiss regulator, Swissmedic, which is expected by the end of 2024. The decision is far from straightforward in the face of so many diverging opinions. The regulator has to weigh the benefits and risks of a drug for a life-threating disease that still isn’t fully understood and hasn’t seen a breakthrough in decades.

The decision won’t just affect thousands of people at risk or living with Alzheimer’s in Switzerland but will also send a signal to drugmakers about how much to invest in new treatments for the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia in the world. Dementia is an overarching term that refers to a range of symptoms affecting cognitive abilities, while Alzheimer’s disease is a specific type of dementia characterised by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline.

Globally, over 55 million people suffer from dementia, up to 70% have Alzheimer’s disease. In Switzerland, some 156,900 people have Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia, and this is expected to rise to 315,400 by 2050 according to the organisation Alzheimer Suisse.

The disease slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually, the ability to carry out simple tasks. The World Health Organization estimates that the disease costs healthcare systems around $1.3 trillion every year.

Many unknowns

The diverging views on lecanemab are a sign of how hard it’s been to make progress on the disease. There’s no conclusive evidence of what actually causes the disease. As of now, there is still no approved blood test to detect whether someone has Alzheimer’s and how much it has progressed.

Drugs to date have only been able to ease symptoms of the disease such as memory loss. But catching the disease at that point is too late because memory loss can’t be reversed.

“You need to treat the disease early, meaning before the brain is damaged,” said Pfeifer. To do so “we need to find out if a person is at risk of developing Alzheimer’s 15 to 20 years before symptoms start.”

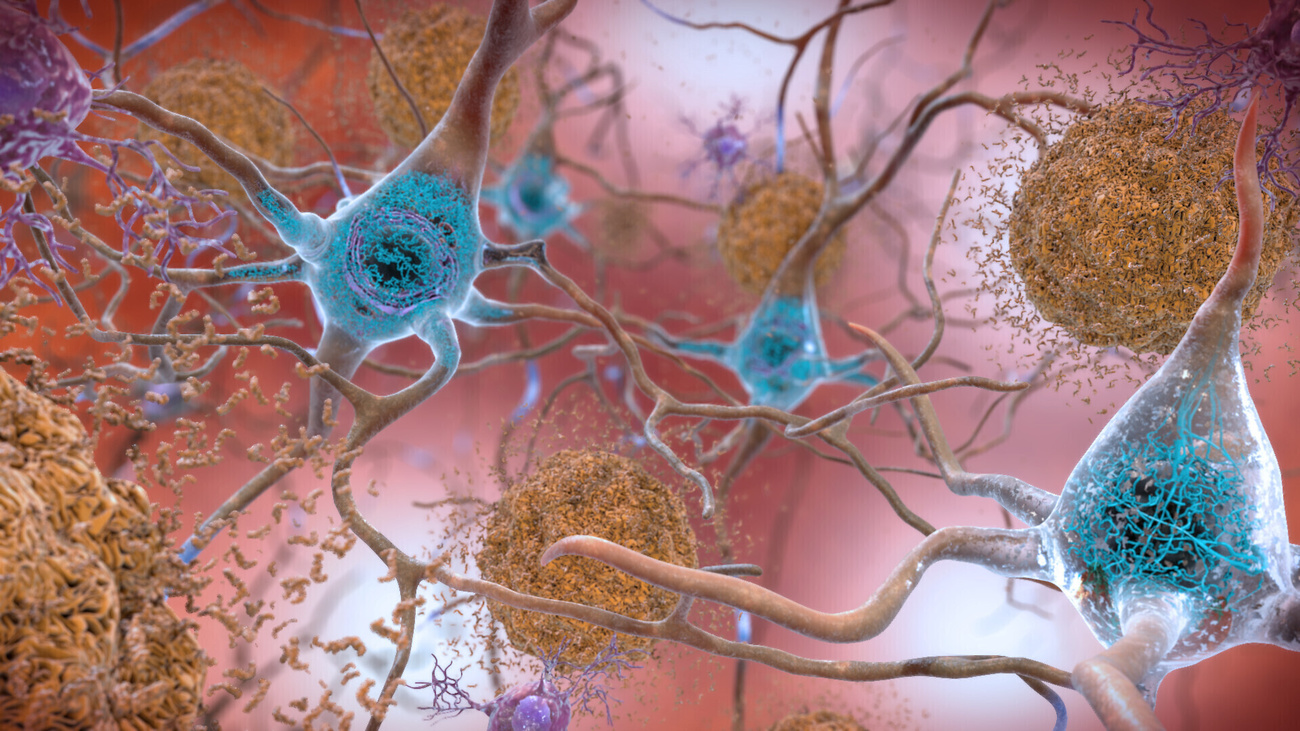

This has led drugmakers to zero in on what happens in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients. Brain scans show unusual levels of amyloid beta protein, which accumulates to form plaques in the brain that disrupt cell function. Lecanemab is part of a new group of drugs that target these plaques.

More

Breakthrough Alzheimer’s drug produced in Switzerland

But measuring the amount of plaque in the brain isn’t enough to say whether the drugs stave off memory loss. Some people who have plaques never go on to develop dementia. Some drugs reduced plaques but didn’t lead to any changes in memory loss or cognition.

Lecanemab, which is sold by US firm Biogen and Japanese firm Eisai, was the first drug that not only reduced plaques in the brain but also slowed symptom progression. The major trialExternal link of the drug with over 1,700 people with early Alzheimer’s showed the drug slowed cognitive decline by 27% compared to a placebo in 18 months.

While researchers celebrated this as a watershed moment for the disease, what it means for patients has been difficult for regulators to interpret. According to some experts, this could keep the dementia at bay for a mere five months. The modest effects might not even be noticeable to a patient or doctor, say some expertsExternal link.

“At an early stage of the disease, the active ingredient reduces the harmful protein deposits in the brain and thus delays the progression of the disease,” wrote Jacqueline Wettstein, a spokesperson for the Alzheimer Suisse association, by email. “However, lecanemab can neither cure nor stop Alzheimer’s disease.”

This benefit also has to be weighed against the side effects including brain swelling or microbleeds that can lead to minor headaches and in some cases, death according to the trial.

When the FDA approved lecanemab, it said the drug was safe and showed clinically meaningful benefit. The European Medicines Agency came to a different conclusion, arguing the “benefits of treatment are not large enough to outweigh the risks associated with Leqembi (lecanemab)”.

Even when regulators have approved the drug, some health insurers, as in the UK, have refused to pay for it, arguing it costs too much for the few benefits it provides. The drug is priced at $26,500 a year in the US but this doesn’t include the costs of the bi-weekly infusions and follow-up.

Rewarding breakthroughs

Antonella Santuccione Chadha, a neuroscientist who worked on Alzheimer’s drug development and now leads the Zurich-based Women’s Brain Foundation, says the benefit-risk equation has to be viewed in the wider context of Alzheimer’s research.

“I understand that the risks associated with these drugs are high relative to the benefits,” said Chadha. “But this may be the price we have to pay to move research forward on this devastating disease that has no cure.”

In the last decade more than 200 research programmes have been either abandoned or have failed in late-stage clinical trials, when drugs are tested in large number of people, according to US-based health researchExternal link firm IQVIA

IQVIA estimates the total costs to develop an Alzheimer’s drug is about $5.6 billion compared with $793.6 million for a cancer drug.

Pfeifer says that US approval of lecanemab sent a message to companies like hers that it is worth the investment. The drug is estimated to generateExternal link $361 million globally in 2024.

“These new drugs may not be perfect cures, but they are slowing cognitive decline in many patients,” said Pfeifer. “If drugs that are at least somewhat effective aren’t approved, who will invest in Alzheimer’s research to bring the next generation of drugs to the market?”

A year after lecanemab was approved, the FDA gave the green light to a second drug, donanemab, sold as Kisunla by US firm Eli Lilly. The UK, European and Australian regulators are still assessing the drug.

More

Swiss research played key role in new Alzheimer’s drug

Some 160 clinicals trials are registered in the US platform clinicaltrials.gov assessing 127 drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. Research is now underway into blood diagnostic tests and new drugs that tackle inflammation and other proteins beyond amyloid beta behind the disease.

AC Immune, the Lausanne-based biotech, has been working for 20 years on diagnostic tests and immunotherapies, that tap the immune cells’ ability to clear plaques from the brain. It now has five drugs in clinical trials, and is also investigating new underlying causes of the disease.

“Every study improves our understanding of the disease. Based on these successes, the next generation will arrive even faster and provide greater benefits and improved safety,” said Pfeifer.

In May 2024, the Japanese firm Takeda and AC Immune sealed a deal worth $100 million up front and potentially billions more later if the company is successful. Under the deal, Takeda has an exclusive option to license global rights to one of its immunotherapies in clinical trials.

Time for a cure

It’s unclear how Swissmedic will rule on lecanemab. Eisai submitted an authorisation application for the drug to Swissmedic in May 2023. In response to SWI, a Swissmedic spokesperson said it can’t share details about a pending decision. It isn’t unusual for the regulator to take more than a year to reach a decision.

More

How drug prices are negotiated in Switzerland and beyond

As Switzerland isn’t part of the European Union, Swissmedic makes decisions independently from the European Medicines Agency. They work with experts to check that the product “meets the requirements for efficacy, quality and safety”.

Last year Swissmedic authorised about 84% (41 new drugs) of new drug applications. The US FDAExternal link approved the same share last year – 84% (55 new drugs).

Even if lecanemab offers minimal benefit, Alzheimer’s patients in Switzerland are hoping for a positive decision. Right now, people in Switzerland can only import the drug at their own expense.

After years of research, we finally have a drug in the home stretch that can at least delay the disease at an early stage, said Wettstein. Lecanemab can’t stop Alzheimer’s disease. “But if it’s given at early stage of the disease, it can give people with the disease more time.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.