Roche’s big bet on big diseases

Swiss pharma giant Roche is the latest company to refocus its R&D investment on diseases like obesity that weigh heavily on healthcare budgets. This comes as governments increasingly demand drugs that save not only lives but also money.

The blockbuster drugs Ozempic and Wegovy have shown there is a goldmine waiting for pharma companies that can develop treatments for mass-market diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Novo Nordisk, the Danish group behind the drugs, has seen its share price surge to record highs this year, making it the most valuable company in Europe with a market capitalisation of over $530 billion (CHF457 billion).

The success of these wonder drugs has injected new energy into the hunt not only for the next-generation weight-loss hit, but for other drugs that can create similar dramatic changes in the treatment of major diseases that affect millions of people worldwide.

Basel-based Roche is the latest pharma giant to announce a revamp of its investment strategy to focus on developing “transformative” drugs, treatments that have a groundbreaking impact on chronic illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, or lung cancer that affect large swathes of the world’s population.

Roche has homed in on 11 diseases in five therapeutic areas, including three — cardiovascular-metabolic disorders such as obesity, along with oncological and neurological diseases – which it estimates will account for more than 50% of the global disease burden in the next ten years.

“We’re really focusing on those areas that have the biggest unmet need, and what health systems will focus on,” Roche veteran Thomas Schinecker, who became CEO in March 2023, told an annual investor meeting in September. “Especially when they have less budget available, they will focus on those areas that can have the biggest impact.”

The shift reflects a new reality where public health budgets are under increasing financial pressure from demographic trends, notably age-related illnesses. Governments are looking for diagnostic tools, treatments and drugs that will benefit hundreds of thousands or even millions of their citizens and stop healthcare costs spiralling out of control.

The World Obesity Federation estimates that 54% of the adult world population will be obese or overweight by 2035, costing the globalExternal link economy over $4 trillion. The marketExternal link for anti-obesity drugs alone could grow to more than $100 billion a year by 2030, according to IQVIA, a global healthcare analytics and research group.

Roche was involved in obesity research two decades ago but exited after only modest success. Now, with the market exploding, the company has dived back in. Earlier this year it paid $2.7 billion to buy Carmot Therapeutics, a small California biotech developing anti-obesity drugs that laid the foundation for an entire research unit for cardiovascular-metabolic diseases at Roche.

Age-related macular degeneration, a leading cause of irreversible blindness, is expected to affect some 288 million people by 2040. DementiaExternal link, including Alzheimer’s, the most common form of the disease, will affect 132 million people worldwide by 2050, up from 47 million in 2015.

More

Medicines regulators weigh hope and hype with new Alzheimer’s drugs

“Imagine a real future where there is an amazingly effective Alzheimer’s drug,” said Bill Coyle, who heads the pharmaceutical division at ZS Associates in Zurich, a global consultancy focused on healthcare. “The willingness to pay will be very high. And this is coupled with a very large patient population.”

Picking winners

Roche’s decision to focus on big diseases isn’t surprising, said Mike Rea, who heads the boutique health consulting firm IDEA Pharma. Most big pharmaceutical companies have moved in a similar direction.

German firm Bayer and US-based Johnson & Johnson along with Novartis have all trimmed their pipelines to focus on similar disease areas, selling off or downgrading business units that have the potential for smaller pay-outs. French pharma giant Sanofi recently said it plans to sellExternal link its consumer health business unit, including its popular over-the-counter medicine Doliprane, to focus on new, higher-priced medicine.

More

What’s behind the Novartis job cuts?

The shift in strategy at Roche couldn’t have come soon enough for investors. The company was riding high for 20 years thanks to a suite of highly profitable cancer drugs. But generic versions are eroding profits for some of those drugs, such as Herceptin, and the company’s share price almost halved in the two years through April 2024 amid a series of clinical trial failures.

“Until five years ago, Roche was pretty golden in terms of oncology. But it isn’t as strong on that anymore,” said Rea. “It now has the challenge of figuring out: how do you change R&D and get closer to what payers are saying that they want — now and five years from now.”

Over the past year, Roche has slashed its development portfolio by 25%, scrapping research into 26 drugs, some of which had already entered clinical trials. This includes treatments for Pompe disease, a rare genetic disorder that causes progressive weakness to the heart and skeletal muscles, and dup15q syndromeExternal link, the most common genetic cause of autism spectrum disorder.

It also cut drug candidates in cancer and neuroscience that didn’t have the potential to beat out competitors and lead to mega-blockbuster status, achieving $3 billion-$5 billion in annual sales at the peak of their lifecycle.

Under its new strategy, Roche says it wants to increase average peak-year sales potential of its pipeline by 40%. Over the past 20 years, average peak sales for launched drugs has been around $4 billion.

Sales peaks of the mega blockbuster magnitude are extremely difficult to achieve with drugs targeted at rare diseases that have few patients and are only used against a single disease (or indication).

In September Roche said it was reallocating resources to speed up the development of three drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, obesity and inflammatory bowel disease, that all have potential for peak annual sales of more than $3 billion.

Cost vs benefit

Treatments for mass-market diseases are also key priorities for public health providers and insurers. Healthcare costs have been rising faster than economic growth in most developed countries, driven by chronic illnesses, long-term care for the elderly, medical advances, and higher drug spending.

In Switzerland, total healthcare expenditureExternal link is expected to increase from 11.3% of GDP in 2019 to 15% by 2050, with long-term care for the elderly taking up a growing share.

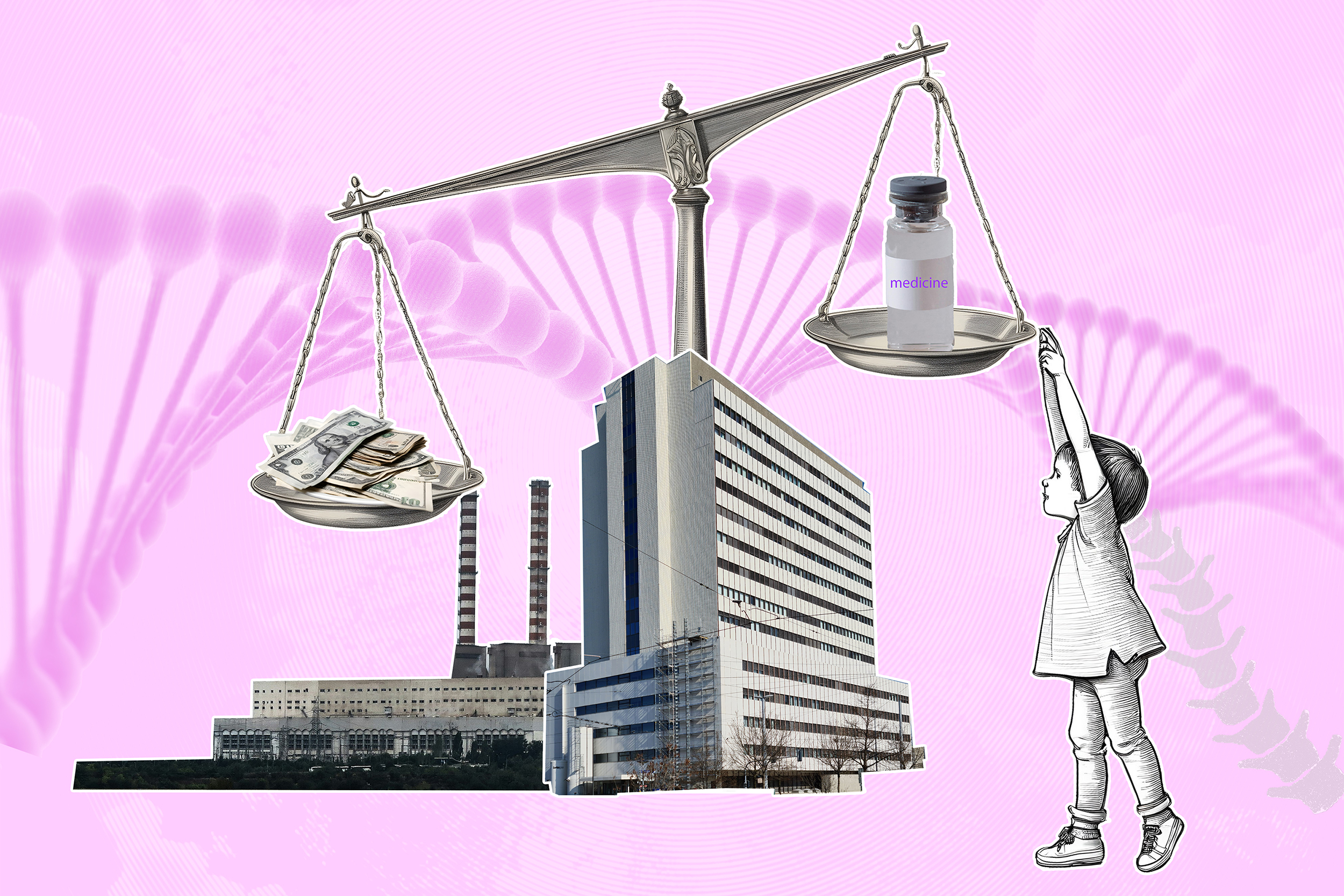

To curb costs, many healthcare payers are demanding that drugs show their value. In addition to evaluating drugs for their safety and efficacy, many healthcare payers are now assessing a drug’s cost-effectiveness — how much benefit it brings in terms of health outcomes and cost savings such as fewer hospital stays relative to the treatment’s costs.

More

Rising Swiss obesity levels: can new fat loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy help?

Insurers have been reluctant to pay for drugs for obesity, viewing it as a lifestyle problem rather than a disease. The World Health Organization recognised obesity as a chronic disease in 1997 but the European Commission only did so in 2021.

But amid growing evidence that the benefits of these new drugs could outweigh the costs, payers are coming under pressure to pay up – pressure that will only increase if prices fall as supply improves and more competitors enter the market.

Some studies have shown that GLP-1 drugs, which mimic a hormone that helps control hunger and is the active ingredient in Ozempic, can lead to weight loss of 15-20% and reduce obesity-related conditions such as heart disease, certain cancers and hypertension. Other studies show GLP-1 drugs could slow the progression of a range of diseases including Alzheimer’s.

The growing interest in developing drugs to treat mass-market diseases that could potentially save healthcare systems billions has coincided with an expected fall-off in the price incentives in the US and EU that previously drove many pharma companies to increase their research budgets for new drugs to treat rare diseases.

Some countries are also pushing back against price tags of as much as $2 million-$3 million for rare-disease drugs even if they can dramatically improve the lives of children with fatal genetic diseases.

“There is clearly a change in the narrative on rare diseases that’s being driven by the reimbursement bodies who have been harping on about value,” said Carina Schey, a health economist in Geneva who works on value models for rare-disease drugs.

As governments become increasingly concerned about how they will pay for the rising costs of treating mass-market diseases, pharmaceutical companies are eager to present themselves as part of the solution rather than the problem.

“Healthcare systems are massively under pressure,” Schinecker told Roche investors at his September presentation. Rising costs “is a trend that won’t be able to go on forever. It’s also our responsibility to help address the costs in the system”.

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm/ts

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.