Swiss regulator and media clash over weight-loss drugs

Swiss medicines regulator Swissmedic has taken legal action against media houses in Switzerland for what they argue is unauthorised advertising for drugs used for weight loss like Ozempic and Wegovy. Swiss media say this amounts to censorship.

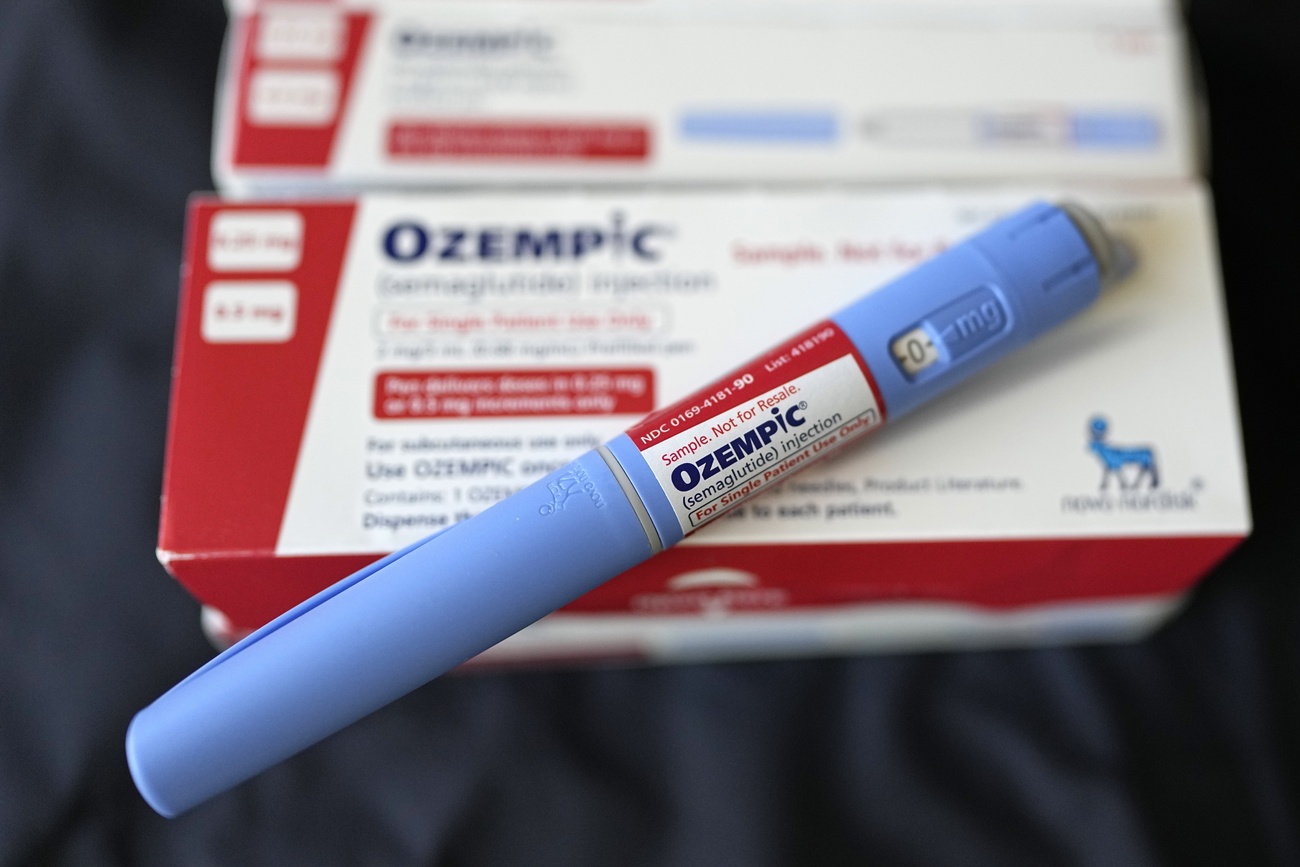

There is no shortage of headlines about the latest GLP-1 drugs used for weight loss, such as Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro. In the last two years alone, there have been over 840 media reports in Switzerland with Ozempic in the headline, according to the Swiss Media Databank.

For Swiss medicines regulator Swissmedic, some of these articles have gone too far in the direction of advertising. Last Tuesday, Swiss daily 20 Minuten reportedExternal link that Swissmedic had ordered three Swiss media groups – Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Ringier and 20 Minuten – “to, under threat of punishment, delete online articles about Ozempic and Co”.

According to Swissmedic, these articles constitute adverts for prescription drugs, which isn’t allowed under the country’s Therapeutic Products Law. This applies to all print, television and electronic media. Both Wegovy and Mounjaro are authorised for weight reduction in Switzerland. Ozempic is authorisedExternal link for Type 2 diabetes and can be used for weight loss if prescribed by a doctor for “off-label use”.

These are not the first or only prescription drugs to provoke legal action by Swissmedic. In addition to articles on obesity in connection with weight-loss drugs, a spokesperson for the NZZ said Swissmedic has also taken issue with an article on migraines and different types of treatment against them.

More

Swiss medicine regulator warns against purchase of fake Ozempic

The latest weight-loss drugs have, however, prompted more questions about how the regulator is interpreting and applying the law amid the public excitement and social media buzz about these drugs and their effects.

“The interpretation of the law by Swissmedic goes too far so that almost all editorial content could suddenly be considered an advertisement,” said Urs Saxer, a law professor at the University of Zurich who is representing one of the media groups in litigation against Swissmedic. “How to lose weight is part and should remain part of the public discussion.”

Around 12% of the Swiss populationExternal link is considered obese. Globally, 1 billion people are living with obesityExternal link. There are thousands, if not millions of TikTok posts and YouTube videos of people sharing their experiences with specific weight-loss injections, which can be viewed from anywhere in the world. It’s also big business – the global market for obesity drugs is estimated to be worth $100 billionExternal link a year for drugmakers alone.

Stringent law

According to legal experts contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch, Swiss law on pharmaceutical advertising to the public is strict compared to countries like the US or New Zealand where advertisements for prescription drugs are allowed on television if benefits and risks are mentioned. Most of Europe has similar laws to Switzerland, banning pharmaceutical advertising to the public.

Article 2 of the OrdinanceExternal link on Advertising for Medicinal Products defines advertising as “all information, marketing and incentive measures aimed at promoting the prescription, dispensing, sale, consumption or use of medicinal products”.

The law is intended to protect people from false or misleading information that could lead to excessive or inappropriate use of products, explains Swissmedic spokesperson Lukas Jaggi. “The Swiss legislator aims to protect public health, ensure transparency and provide the public with factual information on the responsible use of medicinal products,” Jaggi told SWI in an email. “Medicinal products should be used on the basis of medical needs and not for commercial interests.”

The scope of the law is broad so that it applies to anyone who reaches the public, including the media. In most cases, it’s drugmakers or pharmacies that breach the laws – not the media – by publishing brochures that appear promotional, for example. In 2023, Swissmedic, which is mandated to implement the law, investigated 80 cases of potential advertising. Legal proceedings were initiated in 27 cases of which two were for journalistic articles on GLP-1 drugs.

Gray area

It isn’t always clear-cut though when editorial content constitutes advertising. Sylvia Schüpbach, a Swiss lawyer specialising in pharmaceutical law at the Bern-based law firm PharmaLex, says reporting that “aims to change people’s behaviour to the effect that they want to buy or be prescribed a medicinal product or medical device” would be considered advertising.

However, most media don’t intend or aim to advertise products. “It is always the way in which it is formulated that can cross the line between permissible information and advertising,” she said.

More

Roche’s big bet on big diseases

For example, media reports that talk about diseases and medicines wouldn’t be considered advertising but it’s problematic when individual drugs are singled out. In a press releaseExternal link published on January 16, Swissmedic indicated that three conditions need to be met if prescription drugs are mentioned in the context of general-interest topics: all treatment options need to be mentioned, including non-medicinal ones, none of the treatment options should be presented as superior, and both positive and negative aspects of treatment options should be mentioned.

It goes on to say that “reports of patients’ experiences or success stories, price comparisons and recommendations are classed as advertising”.

It isn’t clear what articles Swissmedic found problematic. The regulator currently has four ongoing proceedings with media publishers. The 20 Minuten article last week referenced their own articles, which gives a timelineExternal link of the influencers fuelling demand for weight-loss injections. SWI has not had access to the other articles.

When contacted by SWI on its pending legal cases, the NZZ replied it was “taking legal action to prevent Swissmedic from prohibiting it from publishing journalistic articles but can’t comment on the content due to ongoing proceedings”.

“When you look generally at the reporting in Swiss media on the latest weight-loss drugs, it is debatable whether the information is promotional or not,” says Schüpbach.

The Swiss Media Bank shows articles on GLP-1 drugs covering a range of topics from potential next generation GLP-1 drugs and the latest research on rare side effects to the role of celebrity influencers in fuelling demand as well as problems of falsified versions of Ozempic. Reports like these can be found in media all around the world.

“Journalists are expected to comply with journalistic rules and principles. This includes not making propaganda for products,” said Saxer. “This is completely sufficient. There is no need for additional restrictions under the law on advertising pharmaceutical products. Swissmedic’s interpretation of that law needs to take into account freedom of the media.”

Swissmedic has pushed back on this, arguing that the accusation that it is forbidding all reporting on weight-loss injections is “excessive and incomprehensible”. In an email, Jaggi emphasised that “fact-based and neutral reporting on medicines is easily possible and in the public interest”.

Wild world of social media

The frustration of media organisations also comes from the fact that people in Switzerland can access information about weight-loss drugs from all over the world, including in countries that don’t have the same guardrails on advertising. In the US, drugmakers, online pharmacies, and health clinics have flooded the internetExternal link with advertisements for weight-loss drugs. It only takes a Google search in Switzerland to find these ads on YouTube.

In a press release, Swissmedic said “it carries out regular reviews, which include print, electronic (radio and TV) and online media, as well as social media platforms”. However, it doesn’t screen all editorial contributions from the public media and cannot check every published article, said Jaggi.

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

Swissmedic is obliged to investigate any reports it receives of suspected violations of advertising regulations. These reports could come from anyone including a competitor of the drug’s maker.

If content on social media is brought to its attention, Swissmedic told SWI it would investigate it. However, up to now social media hasn’t faced the same scrutiny as traditional media.

This is in part because most social media platforms and influencers are based outside Switzerland – and therefore beyond Swissmedic’s jurisdiction. It’s also a herculean task to investigate social media. “If Swissmedic wanted to review and possibly ban every positive statement made on social media in Switzerland about prescription-only medicines, it would need a lot more staff,” said Schüpbach.

A 2023 studyExternal link of 100 TikTok videos posted under the hashtag Ozempic found that one third, garnering over 31 million views, included content that “encourages/entices other people to try Ozempic/presents Ozempic as a coveted drug/portrays Ozempic positively”.

More

Poll: Swiss are fed up with social media

Last spring TikTok banned contentExternal link promoting dangerous weight-loss behaviour or facilitating “the trade or marketing of weight-loss or muscle-gain products”. This came after a surge in videos promoting thinness and misleading health information, as well as content creators who were cashing in on promotions of weight-loss drugs. Some content creators pushed backExternal link on the ban, arguing it was discrimination against people who are overweight.

“People want information about how medicines work, and they will go out and look for it,” said Schüpbach. “What’s most important is that they get reliable information.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sb

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.