The fruits of fly research

How do fruit flies use their noses to sniff out the rotting fruits they love so well? That’s what award-winning scientist Richard Benton is trying to understand, and his work could help fight one of Switzerland’s newest invasive pests.

They say you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar, but for University of Lausanne researcher Richard Benton, it’s more than a finger-wagging adage – it’s a testable hypothesis.

Benton’s research passion is the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. More specifically, it is D. melanogaster’s sense of smell, which plays a major role in determining their behaviour.

“My lab is interested in understanding how the fly nose tells the fly brain what odours it detects, and how the brain tells the fly to react to those odours,” Benton tells swissinfo.ch.

The nose knows

The fruit fly has a nose called the antenna, located on the front of its head. It is similar to the human nose, but turned inside out, so all the odour-detecting neurons are on the outside of the fly, making them very accessible to researchers.

A trillion odours

So why choose fruit flies, with their microscopically tiny noses, to study how smell works?

“We use the fruit fly because it is a model system that has been used for over 100 years in the laboratory, so we know a lot about its biology and we have a lot of genetic tools to manipulate its genes and neurons,” Benton explains.

Understanding how fruit flies turn sensory information into actions could shed light on areas of human perception and behaviour that are still an enigma to scientists.

“The mystery of how you detect a natural smell, like coffee or flowers, is a fantastically complicated problem because there are so many different odours in those blends. What it actually means to form that mental image of coffee or flowers is still unclear,” Benton says.

Benton and his 14 lab members at the university’s Centre for Integrative Genomics are interested in the moment when the fruit fly neurons recognise a smell: odour molecules in the air bind to special receptors that sit at the tips of specialised olfactory neurons, triggering activity in the cells. This activity could eventually translate into movement toward a mate or food source, movement away from a threat, or any number of other behavioural responses.

While the precise number of odours that humans can detect is still the subject of scientific debate, recent research suggests it may be in the neighbourhood of one trillion.

A matter of taste

Although fruit flies can be annoying when they appear in our kitchens, their attraction to only rotting foodstuffs means that their culinary preferences seldom overlap with those of humans. But D. melanogaster’s invasive cousin, D. suzukii, has more refined tastes – it prefers fruit fresh off the plant, posing a threat to Swiss crops.

Grape, cherry and berry harvests have faced damage in recent years thanks to D. suzukii, which originated in Asia and was introduced to Switzerland in 2011. Understanding what exactly draws D. suzukii insects to ripe fruit could help researchers figure out ways of steering them away.

Dominique Mazzi is a researcher with Agroscope, the Swiss centre of excellence for agricultural research affiliated with the Federal Office for Agriculture. She leads a national research and development task forceExternal link on D. suzukii. Mazzi says that current levels of crop damage are very hard to estimate due to extreme variation in the fly’s food preferences, which are influenced by several factors including the thickness of a fruit’s skin, and its sugar and acid content.

But one thing is for sure: the economic impact is significant, because D. suzukii goes for those fruits – like cherries and berries – that cannot be sold unless they look pristine and unblemished.

“The consumer is not going to accept a single larvae in these fruits,” Mazzi tells swissinfo.ch.

“And when the fly lays its eggs in wine grapes, it opens them up to secondary bacterial infections and fungi. Then the grapes may develop a vinegar smell, so they can’t be used for wine anymore.”

Taking control

Because the use of pesticides is very tightly controlled in Switzerland, measures to protect crops from D. suzukii will have to include alternatives to chemicals.

“The most successful farms now put in a lot of work into sanitation measures, including quickly removing affected fruits before they can become reservoirs for further fly reproduction”, Mazzi says.

Benton and his colleagues are conducting genetic studies that could help pinpoint the neurons involved in attracting D. suzukii to certain odours. This information could be used to either mask the flies’ sense of smell, or create traps to draw them away from crops.

“If you take a particular olfactory receptor gene and express it in another neuron, and then that neuron becomes sensitive to that odour, then you know that you’ve found a key receptor”, he says.

The Latsis Prize

In February, Richard Benton became the 32nd recipient of Switzerland’s prestigious National Latsis Prize. The non-profit Latsis Foundation has been recognising the best Swiss researchers and educators under 40 since 1983. In addition to the National Prize, worth CHF100,000, it also awards four prizes of CHF25,000 each to researchers at the University of St Gallen, the University of Geneva, and the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Zurich and Lausanne. Winners are selected by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

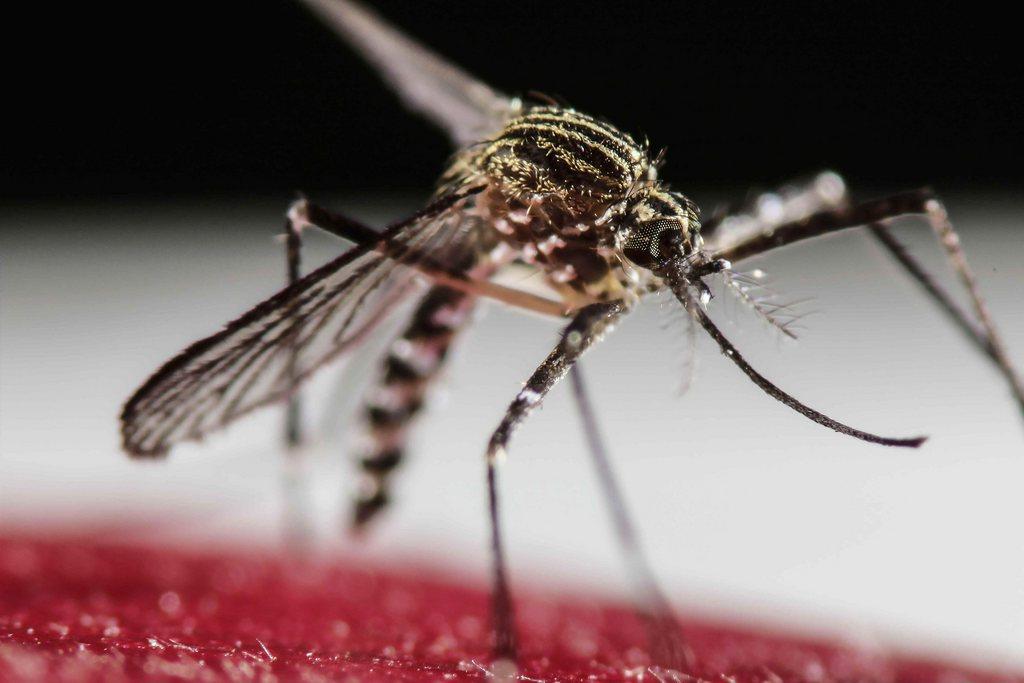

Drosophila suzukii

Drosophila suzukii, also known as the spotted-wing Drosophila or cherry fruit fly, originated in Japan. Its presence in Switzerland was confirmed in 2011, and today it is present in all 26 cantons. D. suzukii prefers healthy late harvest fruits and berries, including grapes, just as they are ripening. It pierces the skin of the fruit to lay its eggs, causing the fruit cell walls to collapse and the juice to ooze out.

More

What fruit flies can teach us about the science of smell

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.