Finding biological parents abroad is an uphill struggle for adoptees

International adoptees in Switzerland face legal hurdles, slow-moving bureaucracy and cultural resistance when trying to trace their origins in faraway lands.

Beena Makhijani doesn’t look forward to birthdays. The youthful-looking 41-year-old, who lives near Zurich, is not scared of growing old.

“I feel strange on my birthday as it is the day I was given away as a baby,” she told swissinfo.ch.

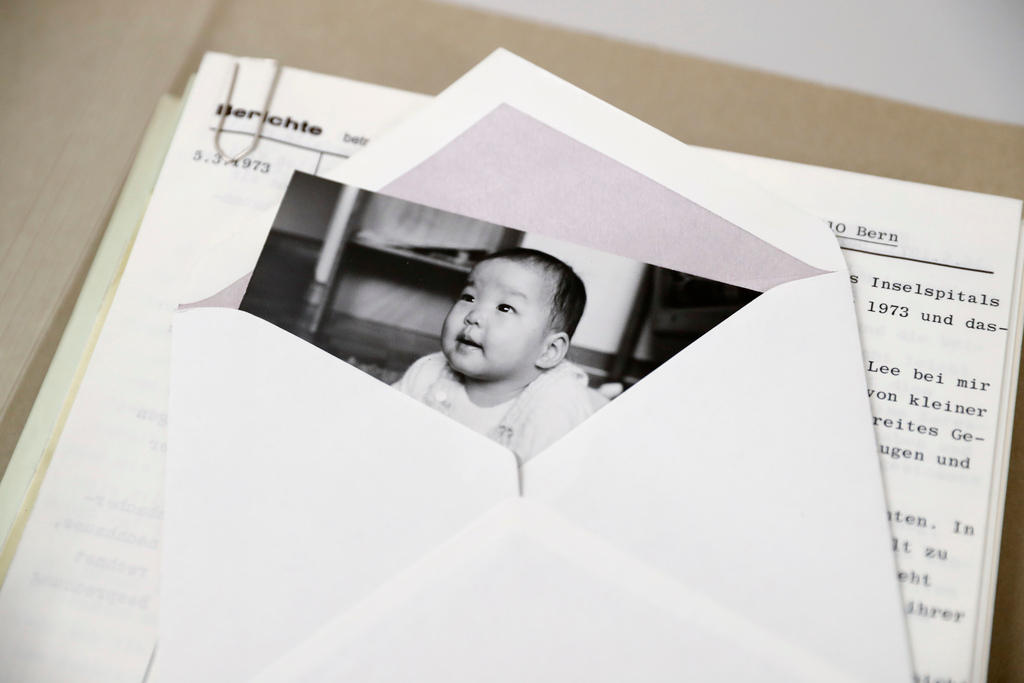

Her Indian mother gave her up for adoption the day she was born. Five months later she was handed over by the adoption agency to her adoptive parents – an Indian man married to a Swiss woman – who were living in India at the time. The family moved back to Switzerland shortly after and two years later Makhijani was formally adopted in her new country. She always knew she was adopted.

“When I was very little I saw a pregnant woman and asked my mother to explain why she looked so different. She told me the woman had a baby in her belly. I asked her if I was like that too and she said no,” says Makhijani.

Her father forbade her from broaching the subject and his relatives in India felt it was disrespectful to raise the issue as they had taken her into their fold and raised her as their own. It was only when she had her first child that Makhijani felt certain that she would embark on a search for her biological parents.

“I always wanted a child as then I could have someone of my own. When I gave birth to my son, I refused to be separated from him for a week. That’s when I knew there was something I needed to resolve,” she says.

Navigating the waters

Beena first went to the Indian embassy in Bern but they couldn’t help and neither could the Swiss authorities nor the International Social ServiceExternal link. A major hurdle was that Makhijani did not have much information about her biological parents to go on.

“The only thing my adoptive parents were told was that my biological mother was 18 years old and had a fair complexion for an Indian,” she says.

Makhijani quickly realised that she needed access to her adoption file to have any chance of locating her biological family. However, the adoption agency in India was unwilling to hand over the information she would need. At the time the right of adoptees to know the identity of their biological parents did not exist.

In 2011 Makhijani enlisted the help of Arun Dohle, a Germany-based anti-child trafficking campaigner who knew the ropes. He – along with his Indian associate Anjali Pawar – have resolved 48 similar cases in India so far but their services don’t come free. Adoptees have to pay €20,000 (CHF21,615) in installments over a seven-year period (they can stop paying after three years if the search is unsuccessful).

“We spend between 200 to 400 hours on each search. The payment model is set up in a way that is fair to everyone,” says Dohle.

More

‘My parents loved me as if I were their own child’

Dohle’s expertise stems from his own experience as an adoptee. He had embarked on a quest to find his biological parents a decade before Makhijani.

“I thought I could solve my case in six weeks. It took two years just to find the right people who could help me,” he says.

Dohle sued the Indian orphanage to make them release the information on his adoption. He finally got access to his adoption documents seven years later when India’s Supreme Court ruled in his favour. He was eventually able to locate and meet his biological mother.

Barriers to information

“We have filed many court cases to get the law changed. At least now the right of adoptees to know their parents is acknowledged but there are still hurdles,” says Dohle.

India’s revised adoption rules are still tilted against adoptees looking for answers. The rules clearly state that the rights of an adopted child shall not infringe on the right to privacy of the biological parents. This makes adoption agencies and government bodies extremely wary about handing over information to adoptees.

+ The law in Switzerland on tracing biological parentsExternal link

Another hurdle is that the law has a clause that third parties cannot do the searches. Hence Dohle had to give up his career as a financial consultant in Germany in order to be present in India for court hearings and meetings with officials and agencies to access his own adoption file.

This is something Makhijani could not afford to do as she has two children to look after in Switzerland. So, she decided to give power of attorney to Dohle and Pawar to access confidential documents on her behalf. But this was not acceptable to the government and the case was taken to court. Last October, the Mumbai High Court ruled in Makhijani’s favour setting an important precedent.

“It is a big victory for all the adoptees who live abroad. My case was adjourned three times and it would have been difficult for me to go to India so many times,” says Makhijani.

More

Is adoption in Switzerland on its way out?

Despite the victory, Indian authorities are still stalling. According to Dohle, they are worried about the consequences for the biological parents. He can understand their reticence.

“Most of the adoptees are living secrets. If you give someone socialised in the West all the information to locate their biological parents they will eventually knock on their door. That will be a scandal and the mothers will suffer the most,” he says.

In an ideal world, Dohle wants the Indian government to keep all the adoption records and assign public social workers to help adoptees find their parents.

“I am not advocating for full access to adoption files like in the West as India is not ready for that yet,” he says.

Beena is still battling to gain access to her adoption file. One of her big fears is that her biological mother is no longer alive and will never know that her daughter is doing well in Switzerland. But ultimately the quest is about finding answers for herself.

“I don’t necessarily want to find my biological parents but I want an explanation. I will not have peace until I know why I was put up for adoption,” she says.

In Switzerland, international adoptions are on the decline. It was most prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s when hundreds of children were adopted from countries like South Korea, India, Sri Lanka, Colombia, Romania, Russia, Ukraine and Ethiopia. The high costs, publicised cases of child trafficking, and new laws and international regulations have put the brakes on inter-country adoptions in recent years.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child External link(that Switzerland is a signatory to) states that inter-country adoption can be considered “if the child cannot be placed in a foster or an adoptive family or cannot in any suitable manner be cared for in the child’s country of origin”.

Dohle is against inter-country adoptions and equates it to legalised child trafficking.

“Switzerland does not send children for adoption to another country even if the standard of living is high there,” he argues.

For Makhijani, being perceived a foreigner while growing up in Switzerland was bothersome but she was lucky to be exposed to Indian culture through her father’s side of the family. It was not knowing why she was given away that proved more challenging.

“I think I will be calmer as I will finally have the answer to a question that I’ve always had,” she says.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.