Neutrality as a business model

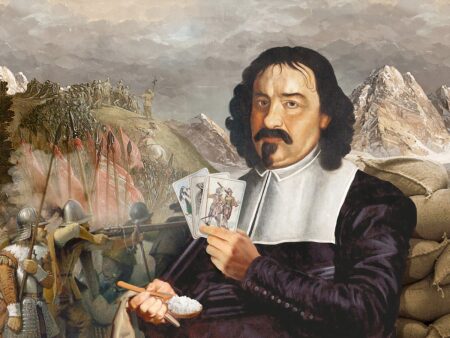

Amidst the turmoil of the Thirty Years’ War, Kaspar Stockalper held three trump cards: the Simplon pass, mercenaries and salt. From the seat of his trading empire in Brig, he developed the cunning yet lucrative strategy of international double dealing.

There was great danger of being drawn into the war raging across Europe in 1639 when Kaspar Stockalper was busy establishing his trading empire in the Simplon area. Large numbers of troops were massed at the borders, several raids and incursions took place, and the powers embroiled in the war had an unending interest in the Alpine region and its important passes. The Confederation was divided along denominational lines, incapable of taking foreign policy action and had no centralised military organisation.

SWI swissinfo.ch regularly publishes articles on historical topics curated directly from the Swiss National Museum’s blog pageExternal link (available in German and often French and English).

Debt collector and diplomat

Fears were also rising in Valais, an associate member of the Confederation, where “due to the circumstances of this present turbulent time and the alarming havoc of war, even a laudable Confederation such as our beloved fatherland finds itself surrounded by large armadas,” as the cantonal parliament duly recorded. Valais was forced to reorganise its military forces and increase its defence capabilities. Stockalper was elected to the Council Of War: as a wealthy and influential merchant at the head of a large international network, he had extensive contacts and access to a wide range of information. He had already been sent to the French ambassador in Solothurn to collect monies owed for Valais mercenaries and to negotiate the supply of further companies of soldiers to France. He was subsequently delegated to attend the Federal Diet in Baden, where he was to represent the Republic of Valais in discussions regarding the turmoil in the Three Leagues and the granting of rights to Spanish troops to march over the local passes. As a result, Stockalper also acquired significant influence in military affairs – and he knew how to put it to good use for business purposes.

At that time, there were 20,000 to 30,000 Swiss mercenaries fighting in the service of foreign powers. All of the parties involved in the war coveted them, the cantons received handsome sums from kings and princes for permission to recruit them, and the private military entrepreneurs that raised, equipped and moved the companies of mercenaries on behalf of the hiring party raked in the cash. Thus, many of Europe’s armies had several thousand Swiss on their payroll. Neither those bidding for their services nor the Confederation saw this as being at odds with the principle of neutrality. The only requirement for doing business was that impartial consideration be given to all the interested parties.

Mercenary service had always been big business in Valais. Members of families entitled to rule, including Stockalper’s ancestors, had been making a name for themselves as leaders of private bands of mercenaries since the Middle Ages. It was a good source of income for the military unit’s owners and officers. The annual payments made in exchange for the right to recruit mercenaries made up a significant share of the canton’s public revenue. And Valais had more than enough peasants’ sons to spare.

France was particularly active, being allowed to recruit at least 6,000 Swiss mercenaries on the basis of a military treaty first signed in 1521 and which had just been renewed. If the Confederation was unable to supply the required numbers, the French king was happy to turn to the independent companies of Valais. Moreover, in 1641 he regularly enlisted the 2,000-strong Ambühl Regiment in his service.

Stockalper himself did not command any troops, but instead made independent military units available to France and Savoy, and probably also Naples and Venice, by hiring them out to commandants or handing them over to officers for a fixed wage. Deals of this kind promised returns of up to 20% with very little risk attached. Stockalper only had to go to Paris in person once, in 1644, when the Valais regiment based there found itself without a leader. However, five companies of 600 men had already been sent off to Spain, in breach of the treaty, to support the Catalan uprisings. They were almost completely wiped out by the Spanish forces in the strategically important town of Lérida (Lleida) in Catalonia. 250 were killed and 200 taken prisoner – a heavy blow for the trade in mercenaries. Yet it has been calculated that, in total, by 1679 Stockalper had earned the equivalent of CHF 48 million in today’s money from this one, continuously growing part of the business alone.

Salt – white gold

Stockalper’s business empire only really began to build momentum when he acquired his most important monopoly in 1647: that of supplying Valais with salt. Salt was indispensable in livestock farming and preserving cheese and meats. Valais had no salt deposits of its own but required up to 750 tonnes a year, and so the state awarded a monopoly concession to supply it with the commodity. As the salt had to be imported from far away, the man in charge of the monopoly was required to have good connections in the trading centres and with the people in government. He also needed sufficient capital to finance procurement, transport and storage in advance. An extensive logistics network was an additional must.

Stockalper ticked all the right boxes. He negotiated a ten-year contract for “supplying the state with salt” under highly favourable terms: in exchange for the exclusive right and obligation to supply salt, he paid a flat-rate fee and received a fixed selling price. Tolls and storage fees were waived. His subcontractors were obliged to pay him for the salt in cold, hard cash at all times, whereas he was free to buy wherever he liked. Depending on the market situation, therefore, he would purchase French, Savoyard, Burgundian, Venetian or Sicilian salt and take his cut. His contract to supply salt was renewed twice and made Stockalper a very rich man indeed.

However, the force actually driving his money-making machine in Brig was the combination of the transit of goods over the Simplon, the trade in mercenaries and the supply of salt, which he merged to create a system that effortlessly fed off itself. He used these three elements to play the major powers off against one another. He supplied the French king with mercenaries in exchange for cheap salt, trading concessions and other special advantages. The French ambassador repeatedly sent word to Paris that “Stockalper gouverne le Valais” or “Stockalper est le chef du Pays du Valais,” advising that he should be given cheap salt so as not to jeopardise the supply of mercenaries. He was known at the French court as “Le roi du Simplon”, the King of Simplon. Stockalper similarly played all his trumps against Habsburg Spain and the Duchy of Milan, allowing that side’s troops to march over the pass in return for cheap salt and other privileges. The crowned heads of Europe were keen to be seen to be favourably disposed towards the man from Brig. Louis XIV made him a knight of the Order of St Michael, he received a Knighthood of the Golden Spur from Pope Urban VIII, the Duke of Savoy named him a baron and Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III elevated him to the rank of Free Imperial Knight.

By pursuing a policy of neutrality in business, Kaspar Stockalper vom Thurm made himself useful through the years to every side in the conflict, prevented the major powers from intervening and played them off against one other while continuing to do business with all of them. In this way, he managed to steer Valais unscathed through a war-torn period, amassing great wealth in the process. The rivalry between France and Spain persisted even after the Peace of Westphalia brought the war to an end in 1648. And so Stockalper’s business model of neutrality and his position in the dealings between the powers remained intact. In 1669, the greatest honour in the land was bestowed upon him: he was elected Landeshauptmann, thus holding the highest legislative, executive and judicial powers in his hands. Having reached the peak of his achievements economically and politically, he appeared untouchable. But things were to work out differently…

The author

Helmut Stalder is a historian, publicist and book author specialising in economic, transport and technical history.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.