No one tortured witches like the Swiss

Swiss witches are making a comeback from the dead as cantons rehabilitate some of those they executed in past centuries - with the last case as recent as 1782.

At a time when many governments are busy apologising for the actions of long-gone predecessors, this may come as no surprise. But when it comes to witches, the Swiss hold the record for persecution.

The French-speaking area of Switzerland executed some 3,500 people, more than anywhere else in Europe per head of population.

From the Middle Ages, there was always a need to find someone to blame for disasters or epidemics. The scapegoat was accused of performing witchcraft or being in league with Satan.

A rebellious attitude or simply being outside the norms of society was enough to attract the attention of the authorities at the time.

The next stage was torture, using methods – including simulated drowning – that would have made anyone admit they had murdered their mother and father, right or wrong.

For researchers, it was torture and religious fanaticism that created witches.

“This imaginary witchcraft, dreamt up by the authorities, is much like the counterterrorism theories that were espoused by the United States,” says historian Kathrin Utz-Tremp.

“I’m not denying the reality of the September 11 attacks, but George Bush gave it mythical proportions to justify the use of torture.”

Between 1429 and 1731, Fribourg put 500 witches, male and female, on trial. The total reached 10,000 for Switzerland as a whole.

Between 70 and 80 per cent were women, and in 60 per cent of cases, the accused were executed.

In Europe, up to 60,000 people were executed over the same period, including 25,000 in Germany.

Imaginary heresy

According to Utz-Tremp, 30,000 to 60,000 people were burnt at the stake for witchcraft in Europe between the 15th and 18th centuries, including 6,000 in Switzerland, of whom 300 were executed in Fribourg.

“In 1429 Fribourg became the third place in Europe to execute witches,” Utz-Tremp told swissinfo.ch. “It was also one of the first places where the political authorities prosecuted people for witchcraft without involving the Church.”

Initially it was the Church, with secular support, that tried first to stamp out heresy and then moved on to magic, turning it into a sort of imaginary heresy.

Utz-Tremp explains that the Inquisition needed this sort of “counter-world” ruled by the Devil, even if it did not correspond to anything in reality.

But in the 16th and 17th centuries, the political authorities took over from the Church in tracking down “witches”. They decided that the practice of any magic, black or white, was based on a pact with the Devil.

Witch hunts

For Utz-Tremp, this is what distinguishes medieval western witchcraft from witchcraft practised in developing nations today, “where there is no religious basis and the Devil plays no part”.

The political authorities used witchcraft trials to assert their position and tighten their grasp on the population, particularly in the countryside.

During the 15th century, most of the trials involved men who refused to submit to the religious or political authorities.

But in the 16th, and even more in the 17th centuries, once secular power was well established, accusations of witchcraft were used to regulate law and order and impose social discipline.

“That’s when the witch hunts really began,” says Utz-Tremp.

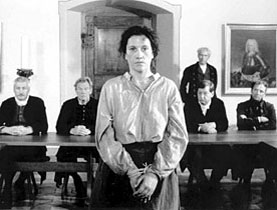

Women made up 70 to 80 per cent of those executed. They were mainly guilty of being poor, single and female, like the Catillon, sentenced to death by a Fribourg court in 1731, and the last woman to die at the stake.

The Catillon, born with a hunch back, was accused of such crimes as stirring up destructive storms with the aid of the Devil, and being able to assume animal shape.

Patchwork state

Witch hunts were much more common in the French-speaking part of Switzerland than in the areas further east.

“In western Switzerland the Church was confronted with the Waldensian heresy, but in the eastern part of the country the trend was more towards white magic, and there was no Inquisition there,” Utz-Tremp said.

Religion has always played a key role in some cantons, including Valais and especially Fribourg.

“Historically speaking, Fribourg was often reactionary. The persecutions were the fruit of the very strict orthodoxy that appeared along with the Counter-Reformation at the end of the 16th century,” she added.

But politics also played a role. A more centralised state, such as France, had less trouble imposing its authority and was less inclined to persecute its citizens.

Patchwork states like the so-called Holy Roman Empire of central Europe, or the loosely bound Swiss confederation, struggled to maintain their grasp on the population. This was also the case even within cantons.

“In canton Fribourg, persecution was particularly bad in the Broye district, which was made up of small communes of which some were Catholic and others Protestant, some German-speaking and others French” Utz-Tremp said.

“The borders there were, the more witches were burned.”

Fortunately today’s witches have nothing to worry about, simply because nobody is interested in them anymore, she added.

“Today a trial like the Catillon’s would be over in five minutes. And besides, there aren’t any laws banning you from flying around on a broomstick!”

Isabelle Eichenberger, swissinfo.ch (adapted from French by Scott Capper)

Witchcraft was considered a heresy and made a criminal offence after 1500 in Swiss cantons. However, most trials in the 17th century were organised by the secular authorities rather than the Church.

In canton Fribourg, Catherine Repond, known as the Catillon, was the last witch burnt at the stake in 1731. She was morally rehabilitated by the cantonal parliament in May 2009.

The last witch to be executed in Europe and the Swiss cantons was Anna Göldi in Glarus in 1782. She was rehabilitated in 2008.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.