Pea-based chicken for lunch, sunflower pork for dinner

Vegan alternatives to meat are finding more and more favour with consumers who are concerned about the environment – and who are prepared to pay a bit more. A Swiss start-up believes it can not only replicate the taste of meat, but even better it. Follow our reporter Sara Ibrahim on the second leg of her journey to becoming a vegan.

The first time I ate a vegan sausage I was very disappointed. It did not taste like meat – or, for that matter, soy or potato starch, as the ingredients indicated. It tasted rather like a piece of toasted plastic. That was five years ago, admittedly. In the meantime, food technology has been making giant strides, driven by increasing demand from consumers. Now imitations of pastrami and cordon bleu are starting to get closer to the originals in terms of look and taste.

More

The challenge of going vegan: why I’m putting engineered foods on my plate

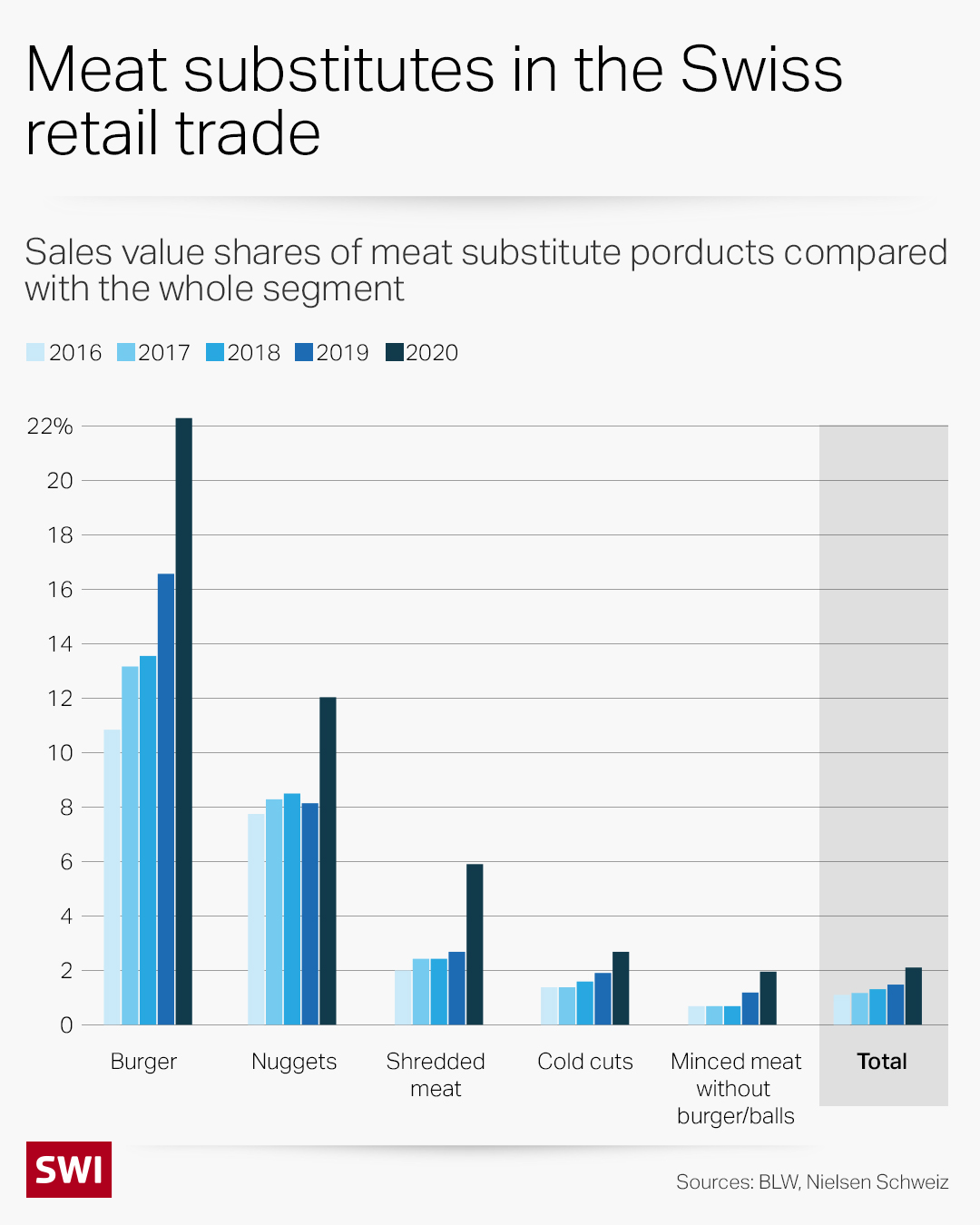

Plant-based meat substitutes are still a niche product, really, with a market share of 2.3% in Switzerland, but sales have doubled since 2016. In supermarkets, one out of every six hamburgers sold is made of vegetable-based ingredients. Vegan products are becoming popular with people who eat everything but want to reduce their consumption of meat, so as to reduce their climate footprint and the use of water and ground resources.

The food-tech scene is taking off in Switzerland, especially in Cantons Fribourg, Vaud and Zurich, where there are several food innovation centres, and, of course, the two federal institutes of technology. Over 160 start-ups have been able to secure 3% of all investmentExternal link made in 2020 (which means about CHF 2.3 billion in total). So the growth potential is considerable.

When we talk about alternative protein, one of the major players on the Swiss scene is Planted Foods, a start-up that began as a spin-off from the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. Its products are available in restaurants and shops throughout Europe, especially in Germany, Austria and France. I found out about this company the way most new brands are discovered these days: on social media. One day, Facebook flashed me a picture of some succulent bits of artificial chicken in pastel-coloured boxes in a sponsored post from which emerged the word “Planted”. It was plain to see that this could not be meat. I had been vegan for several months, but I was looking for some new kind of food that would recall the savour of meat and bring a little variety into my diet.

Appetising ideas

So I clicked on the link, which brought me to the site of Planted Foods. When I found that this start-up was Swiss, I decided to contact one of its four founders, Pascal Bieri, and ask if I could interview him. Bieri met me a few months later in the company’s offices in Kemptthal, half an hour by train from Zurich. It turned out to be just a little way from the station, in a former industrial zone, where broth cubes and instant soups were produced at one time.

I was taken by surprise from the moment I entered. Instead of entering a gloomy factory, I found myself in a restaurant in the middle of a large open space on two levels. “Slaughterhouses hide behind cement walls. We have nothing to hide, though,” says Bieri with a broad smile that contrasts with his grey sweater. Around us people are eating and having informal work chats in what has become the first totally vegan restaurant of the Hiltl chain, which is also open to the public. The owner of the world’s oldest vegetarian restaurant, Rolf Hiltl, was one of the first to invest in Planted.

Prone to sweeping hand gestures, relaxed and quick to laugh, Bieri tells me about his roots. He grew up in a country village near Lucerne where his grandfather raised cattle and pigs. “I had no idea that the meat I was eating had an impact on the planet until I started reading up about livestock raising,” he says. In 2016, while living in the US, he began to reduce his meat consumption. That meant turning to the vegan burger patties made by the company Beyond Meat, until he discovered the long list of highly processed ingredients that went into them. “All those unnatural chemicals which ordinary people know nothing about, ”he recalls.

So in early 2017 he called his cousin Lukas Böni, who at the time was doing a doctorate in food science, and put an idea to him: “Why don’t we create a vegetable alternative to meat that is more natural than what these guys are doing?”. The cousins launched their start-up in July 2019, along with colleagues Eric Stirnemann and Christoph Jenny, and by January 2020 their first product, Planted Chicken, was already available at the Swiss supermarket chain Coop. The company declines to give financial information.

Searching for the perfect protein

Planted’s vegetable-based chicken is made by mixing proteins and fibres of imported peas with canola oil and water from Switzerland. In the case of their “pork strips”, there is protein from sunflower and oats to diversify the profile of amino-acids. The sunflower powder is a by-product of the making of the oil which is very rich in proteins, and which is obtained by crushing the seeds.

Planted works with many different kinds of protein, depending on the product and the manufacturing process. While he explains to me how they get from plants to vegetable meat, Bieri points to a large bag behind a transparent wall. “That is full of fibres and proteins, a kind of flour. At this stage of the process, it’s as if we were bakers”, he quips. I think of him wearing an apron while he rotates a vegetable dough like a pizza. To me, as an Italian, it does not seem at all absurd…

In fact, the proteins, fibres, oil and water are worked on in a machine called an “extruder” to create a hot dough. Extrusion is one of the most popular processes at the moment for creating meat substitutes. But it’s not all that simple. By means of a combination of humidity, heat and mechanical energy, the ingredients are ground down, mixed and homogenised. The dough is then separated to get “chicken” snacks, “pork” strips, or marinated slices.

The structure and consistency of this vegetable “meat” can change markedly depending on the temperature, pressure and amount of water. But the morphological characteristics of the proteins used are basic for getting a high-quality final product.

Meatless chicken

It’s lunch-time. The restaurant springs to life switching the background music to pop. The vegan buffet at the centre looks inviting. It occurs to me, though, that I had seen a 400-gramme box of chicken snacks selling at CHF13.50 ($13.50) on the Planted site. That means over CHF30 per kilo, whereas a kilo of conventional minced chicken at the supermarket costs under CHF 20. “That’s probably the most absurd aspect to the whole thing: as consumers we get meat cheaply, but then we pay for the environmental consequences with our taxes,” Bieri points out.

Bieri notes that often enough farmers can import protein like soy to feed their animals without paying duties, but that does not hold for Swiss producers of vegetable-based meat. In 2020, Switzerland imported over 460,000 tonnes of cereals External linkfor animal feed but only about 245,000 tonnes for human consumption. “If we were to import pea protein and use it as animal feed, we would pay no duties. But as soon as we import it for human consumption, we do pay,” says Bieri, visibly irked. This does not make it easy for businesses like Planted to compete with meat

But Michael Siegrist, a professor and an expert on consumer behaviour at the ETH in Zurich sees the issue differently. “It is true that meat producers get subsidies, but in Switzerland they have to conform to more rules and standards of production and their costs are higher compared to other European countries,” he says. This has an effect on the price of meat, which in Switzerland is over twice as high as the European average.

Not the place for peas

Those who produce plant-based meat substitutes in Switzerland have yet another obstacle to overcome: protein-rich plants like the yellow pea and the chickpea are not easy to cultivate here because soil and sun conditions are less than optimal. Furthermore, there is a lack of large-scale facilities able to extract the proteins and the fibre isolates, which businesses like Planted need, from the raw cereals at competitive prices. “We are trying to find a solution along with the federal agriculture ministry to get the proteins we need in Switzerland, but for the present we have to import them, mostly from France”, says Bieri.

The “chicken” snacks and “pork” strips made of pea protein are just the beginning for Planted. New technologies like 3D printing will progress and will define the next generation of alternative proteins. The start-up is also experimenting with microalgae as a sustainable source of protein. “Our goal is to create vegetable-based proteins with a better taste and consistency than meat,” says Bieri.

Their search for the right raw materials to produce protein-rich alternatives to meat that are sustainable but accessible goes on. Fortunately, Swiss consumers are open to trying new foods, notes Bieri. “Who are you telling?” I say. Sometimes, when I go to the supermarket, I buy products I know nothing about just because they seem strange.

More

It is almost one o’clock and I’m getting hungry. After talking about food for two hours, it’s time to put some in our stomachs. Bieri invites me to try their buffet, but unfortunately I have to run off to another meeting and I have a packed lunch on me. But I know what I am going to cook for dinner: Planted’s “Riz casimir”, a Swiss version of the Indian chicken curry with fried fruits and rice. And I won’t have to tinker with the ingredients to make it vegan.

Keep following me on my travels through the food technologies of the future…

To contact me or comment on the article, e-mail me.

Follow me on TwitterExternal link

Edited by Sabrian Weiss, Virginie Mangin. Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.