Piaget CEO on the evolution of the luxury customer

Benjamin Comar’s appointment as chief executive of Swiss watch and jewellery maker Piaget last summer is a homecoming of sorts.

Three decades ago, the Parisian embarked upon a 12-year stint with Cartier which, like Piaget, is owned by luxury conglomerate Richemont. “I felt at home very easily,” says Comar of his return. The trading of life in gregarious Paris for the serenity of Geneva is another matter, but it is a culture shock he is starting to enjoy – or, at least, embrace.

The industry, however, has moved on since the last time Comar cashed a Richemont pay cheque as Cartier’s head of marketing. As he points out, women buying for themselves – and, indeed, men self-purchasing fine jewellery at all – was not as common then. The slick retail machine that Richemont is today, generating a year-on-year sales uplift of 63% to €8.9 billion (CHF8.94 billion) in the six months to September 30, 2021, was – well – less slick.

During his sojourn outside Richemont, Comar picked up some experience that could stand him in good stead as he tries to bring fresh leadership to Piaget, a company founded as a watchmaker in the Swiss Jura mountains in 1874. This includes a role as fine jewellery director at Chanel and, most recently, as chief executive at jeweller Repossi. These two very different Parisian maisons both required a fighting spirit: Chanel was a fashion house trying to muscle in on the high jewellery market, while disruptive millennial creative director Gaia Repossi’s cutting-edge designs were reinventing what fine jewellery on Place Vendôme could look like.

With big-luxury backing and 119 boutiques scattered across the globe, it seems unlikely Piaget would need to scrap for its place in the market. However, one of Comar’s tasks has been to re-evaluate who the Piaget customer is – especially after the pandemic caused a shift in shopping patterns.

Like all luxury brands, Piaget’s sales figures were historically dominated by tourist spend. So when international travel halted, the majority of that spend dried up. The solution was to focus more on shoppers local to its boutiques and, after a hasty dusting off of little black books, Comar now estimates that 90% of Piaget’s business comes from outside tourist spend. “The idea is to keep that, and then when the tourists come back [capture that spend too],” he says. “That would be the great move of the luxury business in the future.”

When asked about customer demographics beyond location, Comar grimaces. “I have never worked in terms of age or gender or nationality,” he says. “I think, in this world, it’s totally obsolete.” It is also a strategy that Comar believes can be the downfall of brands. “It is the customer that chooses the product, not [the brand who] chooses the customer.”

Kathryn Bishop, foresight editor at consultancy The Future Laboratory, says heritage luxury jewellery brands are still of interest to younger consumers, but such shoppers are looking to these companies to present updated values.

While Comar enjoys being among customers for educational purposes, it seems unlikely he will ever play the celebrity-hugging, yacht-hopping luxury boss stereotype à la watch industry veteran Jean-Claude Biver or jeweller Fawaz Gruosi. His passion for tennis is as far as it goes: “It is a great sport,” he says. “Calm and dynamic at the same time.”

Potential for growth

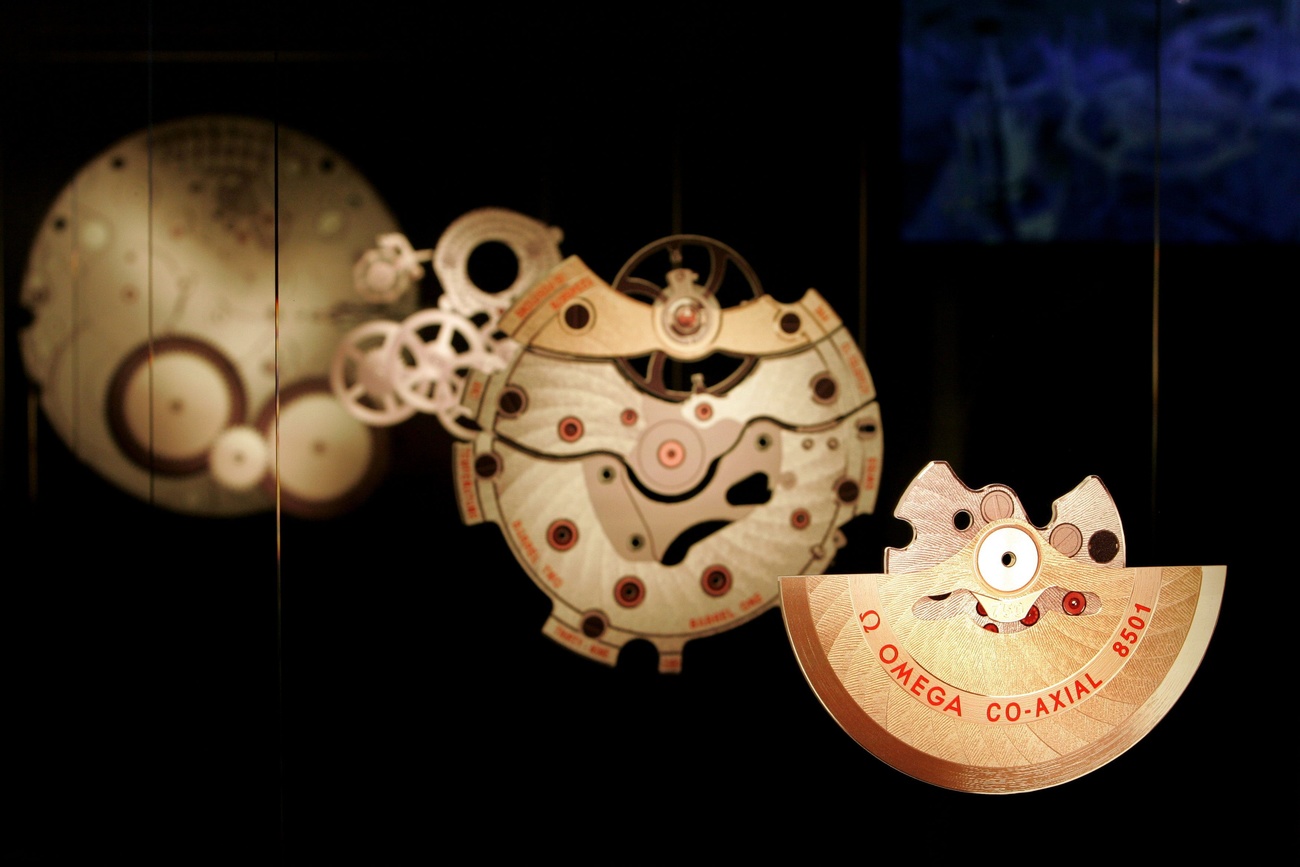

Piaget’s sales are now evenly split between watches and jewellery, although Comar will not reveal figures. Its watches are revolutionary, especially its record-breaking super-thin movements, made at its own manufactures in La Côte-aux-Fées and Plan-les-Ouates. The Piaget Polo Skeleton on Comar’s wrist has a case just 6.5mm thick, while the case of the Altiplano Ultimate Automatic, for which Comar accepted an award for Mechanical Exception at Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève – the Oscars of the watch world – late last year, measures 4.3mm.

Piaget’s jewellery arguably has less of an identity – although this is something Comar denies, pointing to the orb-obsessed Possession collection that first emerged in 1990 as “a renowned icon in the industry”. However, it certainly is not the hot property that Cartier’s Love bangle or Van Cleef & Arpel’s instantly recognisable Alhambra lucky clovers are – the other big jewellery maisons in Richemont’s stable.

When talking about Piaget’s potential for growth, Comar refers to all the factors that have been behind the recent fine jewellery sales boom: the rise in self-purchasing; jewellery being wielded as an “expression of our personality”, even during lockdown; the price of luxury leather rising disproportionately to jewellery; contemporary dressing that calls for stacked rings, layered necklines and laden wrists.

The latest McKinsey report estimates the branded jewellery sector will see compound annual growth rates of 8% to 12% from 2019 to 2025. Martin Crepy, senior partner at the Simon-Kucher & Partners consultancy, says Comar’s growth ambitions are “clearly feasible”, suggesting Piaget should focus on developing “its iconic pieces, heritage and differential value proposition with mastering ornamental stones”.

But if there is one word that Comar keeps returning to when speaking of Piaget, its clients and its creations, then it is “joyful”.

The brand’s true creative heyday – and one that it plunders for inspiration often – was in the 1960s and 1970s when Valentin Piaget pushed boundaries to tempt hedonistic tastemakers du jour, including Andy Warhol and Elizabeth Taylor. This produced icons, such as its textured gold dress watches with small oval faces circled by diamonds, and the swirling jewellery timepiece Limelight Gala, which is still being produced today.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022

More

How the pandemic has widened inequalities in Swiss watchmaking

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.