Switzerland, the League of Nations, and the shadow of revolution

The League of Nations was founded 100 years ago, with Geneva as its headquarters, in response to the First World War, but the Swiss were also convinced to join based on worries about Russia’s Bolshevik revolution.

“Switzerland fights revolution by carrying out all the social reforms it considers possible; our nation is concentrating all its economic and moral resources on this goal,” declared Swiss Foreign Minister Felix Calonder on July 2, 1919, at a meeting with Swiss reporters to outline the country’s plan to join the League of Nations.

The League of Nations was born from the desire not to relive the bloodbath of the First World WarExternal link. This represented a major historical milestone: the League External linkwas the first organisation to deal with international affairs in an institutional manner. The United States President, Woodrow Wilson, was one of the main initiators of the project. Initially reluctant, the European powers finally ratified the League of Nations project.

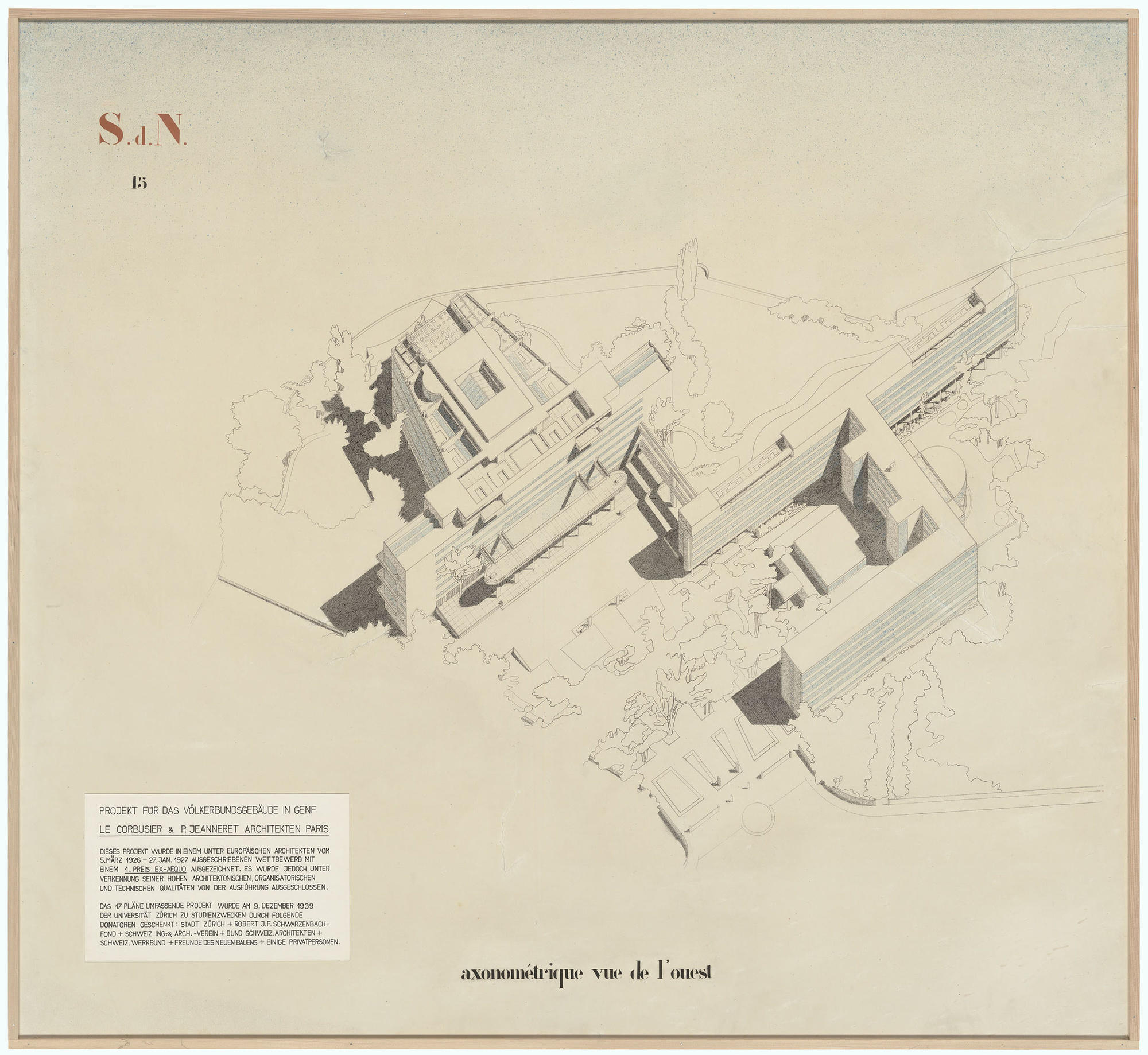

Why Geneva? Since 1863, the city of Calvin has been home to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). But it is mainly thanks to the combined efforts of Federal Councillor Gustave Ador External linkand economist William E. RappardExternal link that the city of Geneva was chosen over Brussels or The Hague. Following a popular vote on May 16, 1920, Swiss citizens decided in favour of joining the new international organisation. This date marks the real beginning of Geneva’s international vocation. The vote was also the first to deal with an international political issue in the history of direct democracy.

It was summer, but on this particular Wednesday the temperatureExternal link hovered at around 15° Celsius (59° Fahrenheit) in the Swiss capital, as in much of Europe. The news was not particularly sunny either. In the wake of the Great War, social unrest and even revolutionary agitation was troubling several European countries, especially Germany and Austria. The fear aroused by the Russian revolution and the seizure of power there by the Bolsheviks haunted states that had just signed the Versailles peace treaty.

The Swiss foreign minister saw a solution: “There is only one way out of this chaotic situation where passions are being unleashed. Instead of the mechanical sort of balance of power which has obtained until now [since the treaty of WestphaliaExternal link in 1648], there needs to be a moral balance, provided by the League of Nations. Peace between nations is a condition of social peace within states.”

‘The atrocities of the Russian revolution’

Calonder then hammered his point home: “Should Swiss democracy really stand aside waiting for the inevitable explosion, and refuse to join the League of Nations? The atrocities of the Russian revolution and the terrible trials visited on other nations by the dictatorship of the proletariat – are these not enough?”

The revolutionary ferment troubled the Swiss government all the more because it overshadowed the proposal to establish the League of Nations in Geneva.

A telegramExternal link addressed in August that year to Calonder by the legation (embassy) of Switzerland in Paris emphasised this aspect by quoting two reasons which, according to the French government, might stand in the way of the League establishing itself in Geneva: “First: insufficient majority vote at the referendum to join the League of Nations [it would be won on May 16, 1920]. Second: aggravation of Bolshevik machinations in Switzerland and too much tolerance shown by the authorities towards the ringleaders.”

In a report External linkaddressed to the foreign minister a month later, ambassador Alphonse Dunant was even more to the point: “On several occasions, this legation has had the honour to inform you that the Bolshevik agitation which has occasionally taken place in our country was being used by certain circles as a reason to campaign against the choice of Geneva as seat of the League of Nations – and for that honour to be taken from us and given to Brussels.”

A source of worldwide revolution

It is hard today to imagine Switzerland as a source of worldwide revolution. But that was the apprehension of the Allies beginning in the autumn of 1918. It meant an initial diplomatic defeat for Switzerland, which had offered to host the peace conference, whereas it was finally held in Paris, as historian Hans Beat Kunz noted in an articleExternal link written in 1982:

The Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (DodisExternal link) are set to publish an online dossier in September on the 100th anniversary of the League of Nations.

The Dodis research centre, an institute of the Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Science in Bern, focuses on the history of Swiss foreign policy and international relations since the creation of the federal state in 1848.

“In January 1919, Colonel House, an adviser to the American president, told Swiss president Gustave AdorExternal link ‘that the Peace Conference almost took place in Geneva in early November 1918 under the aegis of President Wilson, who had suggested the idea. England was favourable, Italy was enthusiastic and France was about to concur too when the outbreak of the general strike in Switzerland abruptly changed its mind.’ At this point the federal government came to realise that the diplomatic defeat had been due to the unsettled situation within the country.”

Such outside pressures plus some false rumours explain the show of force by the Swiss authorities in the face of a workers’ mass demonstration planned for Zurich in November 1918 to commemorate the Russian revolution. This in turn led to a call for a general strike from the OltenExternal link committee, formed by socialists – both politicians and trade unionists – to direct the general strike of November 1918.

What about neutrality?

As the work of several historians has shown, there was little real risk of revolution in Switzerland at the time, despite considerable social unrest. But the argument influenced the domestic and foreign policy of Switzerland for a long time. Faced with the “red tide”, it was no longer a question of neutrality.

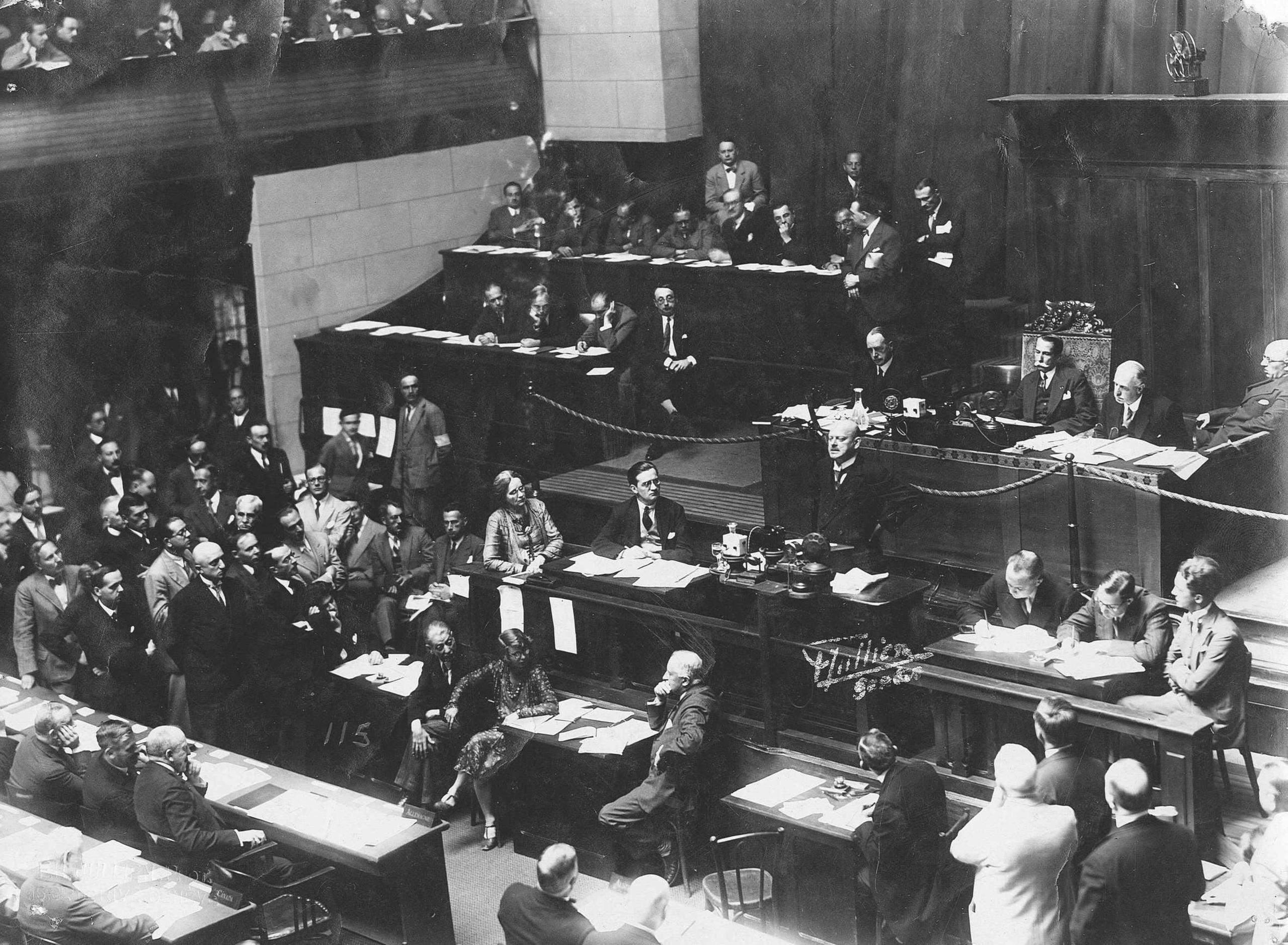

This attitude was hammered home by minister Giuseppe MottaExternal link at the sixth committee of the League’s assembly, on September 17, 1934, to explain Switzerland’s opposition to the entry of the USSR to the League. It was a fiery speechExternal link which caused a sensation.

Having enumerated the misdeeds of the Soviet regime, the then Swiss foreign minister took issue with the main argument of the proponents – who would ultimately be successful – for letting Russia into the League:

“It has been noted that the USSR is an immense territory with a population of 160 million people. This being a state looking towards Asia and back towards Europe, bridging two continents as it were, it would be dangerous to ignore and isolate it. The League of Nations is just a new form of international cooperation; it is not a moral instance, but a political association aimed at avoiding wars and maintaining peace. If admitting Russia serves the cause of peace, we must accept this course of action notwithstanding any fears, scruples or aversions that many governments may have. It is even to be hoped that continued cooperation between Soviet Russia and other states in the League of Nations will mean benefits for all, and most of all for Russia itself.”

Switzerland does not believe this is likely, however:

“The Swiss government, which still maintains its friendship with the Russian people, has never legally recognised the current regime. It intends to maintain this position of rejection and waiting. Our legation in Petrograd [today’s St Petersburg] was looted in 1918 and one of its officials murdered. We have never received so much as a hint of an apology. When in 1918 an attempted general strike almost plunged us into civil war, a Soviet mission we had tolerated in Bern had to be expelled, manu militari, because it was involved in the agitation.”

This was a hard-headed stance which Switzerland would notably fail to maintain in its dealings with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. But these regimes were seen by some of the Swiss and European elites precisely as a bulwark against Bolshevik revolution.

More

When League of Nations reporters put Geneva on the map

Translated from French by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.